ESG Investing Won't Save the Planet

Optimism is needed to provide solutions, but is in short supply

Are you optimistic or pessimistic? The answer determines how you invest. But does sustainable investing offer both options? It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

When I quit fund management to be a research broker, my disapproving boss told me I’d be paid for opinions while he was paid to be right. It’s a great line and what you must tell yourself to turn up each day in an industry that collectively fails to beat the market. You pay your manager to be optimistic, but are they?

Optimists and Pessimists

The difference between an optimist and a pessimist is that the optimist is right.

One of history’s most famous pessimists was Thomas Malthus. In 1798 he wrote an essay arguing that because improvements in human wellbeing led to more humans, rather than a higher standard of living, we would exhaust the earth’s resources. Malthus used some maths, but because he didn’t apply exponential functions, he was wrong.

Exponential growth involves doubling. If you stacked 50 sheets of paper 0.1 millimetres thick you would have a pile 5 millimetres high. But if you could fold a sheet of paper 50 times it would be over 100 million kilometres high, which is quite a difference. Exponential functions start off slowly and can be overlooked in the early stages.

Malthus may have died 189 years ago but he is very much alive and well. Mo Gawdat, a former Google employee, tells people to put off having children in case artificial intelligence enslaves them. Once again, bad news sells.

The claim is compelling for a number of reasons. Few people understand artificial intelligence and we are afraid of the unknown. Gawdat was Chief Business Officer at Google and therefore is an expert worth listening to, and over two and a half million people have watched his interview with Steven Bartlett. They can’t all be wrong and anyway, this is what The Terminator films were telling us.

Optimists tend to get on with things and therefore aren’t as prominent as pessimists. David Deutsch is a pioneer of quantum computing and a leading proponent of optimism, which he defines as:

The proposition that all evils are due to a lack of knowledge, and that knowledge is attainable by the methods of reason and science.

He adds,

There are no insuperable impediments to the creation of knowledge other than laws of physics

What does this mean?

Certainty and Knowledge

Optimists believe that what we know today can be better. Newton improved on Galileo and was in turn bettered by Einstein. Because the pioneers of the past have done the hard work, we get a head start in our thinking and are able to make progress.

This means that we are never certain of something. We know things to the best of our abilities, but these can be improved by what comes next. Hold onto a belief too firmly and, like Malthus, you will be proved wrong.

Gawdat’s pessimism centres on three certainties, which are that AI surpasses human intelligence, that it will be or be used for evil, and that there is not enough time to do anything about it. We are powerless unless we unplug the machine. This is Terminator 2, while the latter franchise films assume this is not possible.

The comparison with sustainability is compelling. Marketing of sustainable investments often starts with the negative consequences of business as usual and the concept of boundaries and limits that we are certain exist. While all investments carry the warning that past performance is no guide to the future, this does not apply to the marketing of sustainability.

Measurement of the earth’s temperature is conclusive. It is rising, as is the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The trend keeps on regardless of all good intentions1.

Exasperation with the failure of government to change anything is a form of pessimism. It leads to calls to stop doing things, including banning fossil fuels, not eating meat and avoiding having children. The hard science of rising temperatures melts into the soft science of deadlines for action.

Not all sustainable investing is negative. Optimists don’t deny that climate is changing, but they focus on adapting rather than banning things that, like Skynet in the Terminator films, will find a way to happen regardless.

Scarcity

Optimists believe that there is no such thing as scarcity. We’re surrounded by resources, but have yet to develop the knowledge of how to use them. Companies such as SpaceX are founded on the basis we are not confined to using the earth’s resources. The cost of rocket launches has fallen 100x in the last 20 years and is expected to do so again in the next decade.

We are not short of water, but of freshwater. 97.5% of water is salty, 2% is ice and we fight over 0.5%. We can focus on curbing the use of freshwater and hope not to worsen the fighting, or we can throw our energies into desalination.

This week Apple launched Vison Pro. It allows wearers to continue interacting with the real world, while simultaneously viewing digital content. Pessimists note there is little need for this, while optimists say we are two doublings away from virtual reality being higher resolution than the human eye.

The cost of solar panels has fallen 80% in the past ten years and its capacity doubles every 22 months. The International Renewable Energy Agency says that solar could produce a quarter of the world’s electricity demand by 2050. Peter Diamandis, founder of the X Prize Foundation that sponsors solutions, argues exponential progress means solar will meet all demand in eight years. You’ll invest differently depending on who you believe.

Who do the fund managers think you believe?

The ESG Marketing Machine

Fund managers earn a small portion of the total amount they control. The faster that grows, the more profits they make. Stock markets rise slowly, at around 7% a year in the UK, and its much quicker to grow by launching new funds.

Managers charge more if you use their expertise to invest. In the US, more than half of all funds track a benchmark, which can be done at very low cost, but in Europe it is the other way around, with most funds pursuing higher goals. More than four in five ESG funds in Europe are managed this way and provide a big boost to managers’ profits.

One of the first sightings of ESG was in a United Nations report into responsible investment, co-authored with the fund industry. While the scientists argued that environmental, social and governance risks should be treated separately, the fund managers nodded along and then went ahead and combined them into a single score.

Most of the sustainable funds you buy today are based on an ESG ranking of companies. What goes into those rankings is a mystery, which is the way the fund managers like it. You need to buy their expertise to understand this stuff, and they spit out a single number to show they were right. Talk about marking your own homework.

In order to grow profits faster, fund managers want to attract money into ESG funds. They need to persuade new and existing investors that sustainability is both best for the planet and for your retirement pot. This requires aggressive marketing.

21x Nonsense

Aviva is the UK’s second largest pension provider and Nest, which was set up by the government, is the third. Both market sustainable investments using a report Aviva produced with Route22, a sustainability company, and promoted by Make My Money Matter, a charity dedicated to greening your money.

The report claims that switching your pension to an Aviva sustainable pension fund lowers your carbon footprint 21 times more than changing your lifestyle to travel by train and go vegan. Given how hard lifestyle changes are, this is an easy fix with huge benefits. It’s also nonsense.

When Covid-19 struck we all stopped flying. Within weeks the airlines were on their knees and required over $400 billion worldwide of government support3. During the pandemic, reduced transport and industrial activity meant pollution in the air over London fell by up to half4.

Not flying is a very effective way of reducing your carbon footprint. If we all stopped flying airlines would close. If the one third of assets invested sustainably didn’t buy airline shares, planes would still fly. Aviva’s claim, reused by Nest, fails common sense.

Nest is no stranger to this kind of misinformation. Its website quotes unnamed research that companies on the London Stock Exchange have ten times more profits if at least one in three of the bosses is female. One fact implies another and all companies should have more women bosses.

Gender equality is fine in its own right and we would not want the 1 in 3 to become a target or ceiling. The implication that it results in a tenfold increase in company profits is not. Maybe large companies chose to employ more women bosses after they grew profits.

If you care about outcomes, then you will be unconcerned how greater gender inequality came about. If you want your pension to deliver decent retirement income you may not want it managed based on readily refutable opinions.

The Purpose of Investment

Stock markets were formed to provide risk capital for entrepreneurs. Nowadays that role is performed by venture capital and other private investors, whose assets are in large part off limits to ordinary savers. Your pension fund gives you little exposure to the start-up technologies developing AI, climate tech and other exponential technologies.

Your pension manager mostly buys the shares and debts of large companies and governments. The establishment doesn’t do innovation, which is why there is a rush into the few large companies with exposure to new technology whenever an investment narrative develops. Hence the share price of Nvidia, whose semiconductor chips built for gaming have potentially even more use in AI.

Investment managers buy shares from other investment managers. Money does not go to the company, or support development of new technology. Occasionally new companies come to the market and temporary scarcity in their shares can jam the price higher. Most of the time however, investing means money sloshing back and forwards between fund managers.

This is a reason why active fund managers as a whole do not outperform the market. When one buys another sells, and only one will be right about the direction of share prices. Deduct fees and as a whole the industry fails to beat the market.

How Sustainable Investing Works

As most of the time your ESG fund is not supplying the capital for companies to invest, its purpose is to send a signal to the company. This takes two forms. One is the effect on the share price and the other is how your fund manager engages with the company on your behalf.

If more money flows into sustainable funds than general funds, and sustainable funds buy and avoid similar companies, then the share price of sustainable companies will do better than the market in general. This happened a lot over the past five years, albeit interrupted by the Ukraine war and surging energy prices in 2022.

As both sustainable and general funds buy a lot of technology shares, this explains why whenever money is flowing into funds, companies such as Apple, Google and Microsoft do well.

The primary determinant of whether sustainable investing delivers decent returns is the amount of people buying sustainable funds. Hence the aggressive marketing. One favourite pitch is that all companies will be sustainable or go bust, so better buy sustainable now.

The logic of this depends on how companies become sustainable. If the bad ones go bust and the sustainable funds don’t own them while the general ones do, then the sustainable funds win. If the bad ones adapt and become sustainable, then the general funds win because they bought before the sustainable funds. Avoidance and adaptation don’t both win.

This logic applies to regulation. If unsustainable companies become sustainable due to regulation, then the general funds that backed them first do well. Most sustainable finance regulation aims to use the flow of investments to deliver a more sustainable economy.

It’s unclear how not investing in something, such as airlines in the Covid example, delivers sustainability, as opposed to waiting for it to happen. It makes no sense to me why ESG fund managers that don’t own companies argue for their regulation, because if it works it hurts their investments. There again, it makes no sense to me why if you believe AI will enslave your children or it’s too late to save the planet, you would invest for retirement.

How to Invest Sustainably

If you line up all the households in the UK up from poorest to richest, the one in the middle has a wealth of £286,600. For most of us, our wealth is in our home. Only two in ten have most of their money in private pensions.

If you want to use pensions and investments to change the world, you are asking richer people to do things that impact everyone. This can lead to an attitude of “it’s for their own good”, which is the thinking behind many of the restrictions on how we are allowed to invest. Still, most of us have some pension provision, so how might we invest it sustainably.

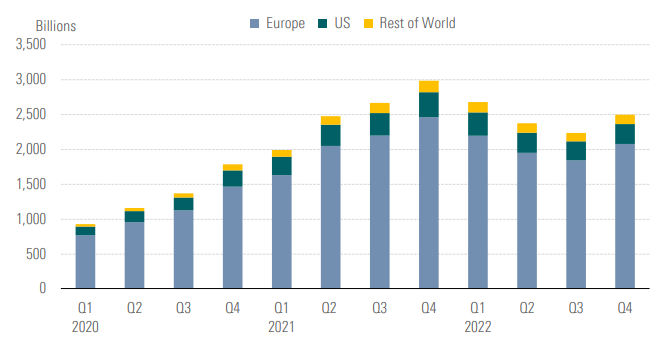

Europe dominates sustainable funds, with over three quarters located there. There was a dip in 2022, but we’re getting over it.

Morningstar reckons there are $2.5 trillion worth of sustainable funds, which are those that most investors could buy. If you invest through a pension, then your provider determines what you have access to, but generally ordinary savers may buy these funds.

There is a much larger estimate of sustainable assets, provided by the industry in each country, albeit with varying definitions. US investors are prominent on this count and a lot of money is invested in negative screening, i.e. avoiding companies.

By this count, sustainable assets are $35 trillion, one in three of all global investments with the majority out of reach of ordinary savers. If sustainable investing is changing the world we’re merely passengers on the bus. There is some double counting in the chart where funds have more than one strategy, but four dollars in ten avoids companies and industries, while less than one dollar is focused on supporting positive change.

Soros Fund Management is an example of a firm committed to net zero emissions that is closed to ordinary investors. Of the $25 billion committed, only $1.3 billion is in climate solutions. There are not enough early stage companies to absorb the firm’s money at reasonable prices and deliver a solution on time. Most investment is in the transition of highly polluting companies to net zero.

Even were there more start up solutions, you cannot buy them. Venture capital is considered too risky for your limited understanding by the powers that be. You must stick with funds buying big company shares and bonds, but you can look for adaptation as Soros does.

If you have a company supplied pension, big providers such as Legal and General, Aviva or Nest offer a limited choice of funds, but it may still be too many. Nest offers five funds, but almost all of its 12 million members own a retirement fund based on when they expect to stop work.

If you are self employed or run your own pension, you will likely also use a big provider for the tax benefits. Your choice of funds, however, may be different to other pensioners and you will need to dive into the specifics to figure out how managers invest.

You will realise that there are different rules for what is sustainable, when companies are excluded and how much of a fund is sustainably invested. Once you have read all the reports you may be no clearer. Hence you go with the default fund, or use price performance as your guide.

As sustainable funds select from fewer shares than are on the whole market, the fund will rise and fall more than the market. Whether it does better depends on when you look and how many other people were buying the companies it holds. There will be sustainable funds doing better than their benchmark and others doing worse. Remember, past performance is no guide to the future.

You Won’t Stop Progress

Pessimists believe that we have gone far enough and must stop now. The problem with this is that we are left with half built solutions that are worse than the problem. Rowan Atkinson argues5 that electric vehicles are not fit for purpose, and the solution is to focus on new fuels for existing engines. Porsche and JCB are leading lights in this development, so should we avoid them for their polluting past, or invest for their sustainable future.

How you see the world will shape your answer. If you are an optimist then you may prefer to invest in solutions to problems, but unless you are already rich this is hard. You will need to look for funds that engage with companies and adapt, such as best-in-class funds that buy the most sustainable companies in each industry.

If you are more pessimistic you will want to invest in funds that avoid certain industries. This is easier because most funds are based on excluding things someone has decided are bad. These choices put you on a collision course with the optimists who go looking for problems and use exponential technologies to solve them. That’s fine as it’s your choice, but don’t claim you are investing to save the planet, because that fails The Sniff Test.

COP is Conference of the Parties UN Climate Change Conference

https://www.aviva.com/sustainability/communities/powerofyourpension/

International Air Transport Association

London Air Quality Network

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jun/03/electric-vehicles-early-adopter-petrol-car-ev-environment-rowan-atkinson?CMP=share_btn_tw