The Rise of the Doomsday Theory

Politicians and investors increasingly turn to disaster theories to predict the future. Does history repeat and can we learn from it? It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

Have you ever asked yourself what you would fight for?

Love, marriage and family, but beyond that. What would make you take to the streets, not just for a day, but again and again?

People protest all the time. Hospital closures, road pricing schemes, local matters that flit in and out of the public consciousness. Clashes with authority and disruptive vandalism attract greater attention, but mostly fade into the background. An era ends though, when a spark ignites the flame.

Politicians, investors, academics and journalists sense something febrile in the air. Change is coming. If you find this inconceivable, remember no one expects the unexpected.

A New Technology Age

We are entering a new age of technology. Whether it will be named for artificial intelligence or renewable energy remains to be seen, but there are big battles to be fought. Trillions of dollars are staked on the assumption that things continue as they are.

Europe is poorly placed in this battle. The advantages that put it at the heart of the industrial revolution no longer apply. New technology requires foreign minerals for hardware, data that is constrained by privacy laws, and continental scale manufacturing, rather than national policies to promote industries.

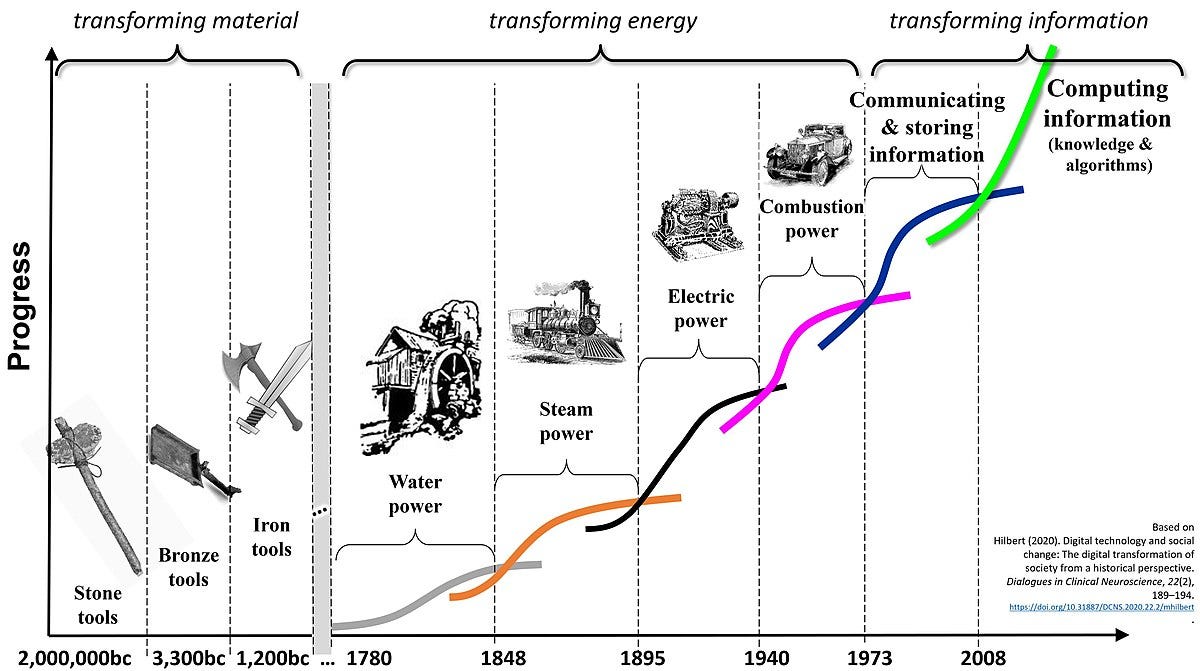

Cycles are dangerous. The first I learned about was the Kondratiev Cycle, which is a 40-60 year trend in agricultural prices accompanying changes in technology. Here’s a modern representation.

The dates are suspiciously precise and Kondratiev’s methods were flawed, but that is not what made it dangerous. Cycles have upswings as well as down and the theory did not spell the inevitable demise of capitalism. Kondratiev was shot by Stalin’s secret police.

The Fourth Turning is Here

Strauss and Howe’s generational theory is extremely popular among financial elites. It tells of a crisis period every four generations, driven by a collective loss of memory of the horrors and deprivations of war, as older populations pass away. Interest in the theory was piqued by Brexit and the election of Trump, and Howe recently published a follow-up entitled “The Fourth Turning is Here.”

Howe predicts a decade of upheaval, before a millennial emerges to lead the rebirth. Before then, nations will call on a grey general in a last stand to save the old order. With the election of Trump and then Biden, and another head-to-head looming, people are paying attention.

A sound theory provides the best explanation for the evidence and does not vary when the assumptions change. Two plus two is always four. By contrast, if I bulk up in the gym, it would be wrong to believe my children would be naturally strong. There is nothing unique about gym conditioning or strength, and if we inherited all the traits that our parents developed, we would be much closer copies of them.

A theory should also be capable of prediction and surviving new evidence when it emerges. Once established, a theory is overturned only when a superior explanation better fits the evidence. Even then, the old theory will have its adherents who are reluctant to change.

The importance of explanations

Howe surveys the evidence and makes a prediction, but we still need a robust explanation of why the theory works. He calls this age location in history. Our formative years shape our beliefs and our reactions to world events are shared by those of a similar age. Climate change matters more to those who expect to live with it.

Once the cycle is established, it is self-reinforcing and a familiar pattern emerges. A post-crisis high is characterised by community and undermined by conformism. An awakening follows, typified by autonomy and protest, such as in the late 1960s.

While this subsides, the third generation favours individualism, which undermines political institutions. Think of Brexit or the questioning of US election results. Finally, this encourages culture wars ahead of the destructive crisis that leads to rebirth.

The primary criticism of Howe’s thinking demonstrates the culture wars he predicts. One-time chief strategist of the Trump White House, Steve Bannon, is a known proponent of the theory, making it an anathema to many on the left. Bannon is accused of instigating a fourth turning. Were this possible, it would be equally possible to stop it, and the fact we can’t or don’t is the real weakness of the theory.

To be inevitable is deterministic. In order to believe something, we also need to believe that without it things would be different. If cycles recur without an alternative, then we are left with a description of them, but not an explanation. The charts and tables look convincing, because you see what is there and not what is not.

The Fourth Turning is an entertaining and persuasive read, given its presentation of the facts. Its scope is too broad however, covering politics, economics, culture, gender, demographics and collective consciousness, to stand up to the rifle shots of academic criticism.

The Storm Before the Calm

Geopolitics uses geography to set the scene for politics. The discipline was popularised by Tim Marshall’s “Prisoners of Geography” explaining the world through maps.

George Friedman does something similar, for example in his take on China’s political imperatives. By rotating a map and looking out over the East and South China Seas, we understand the significance of Taiwan and what US control of the Western Pacific means to Beijing.

Friedman goes beyond maps, however, making both annual and longer-term predictions and reviewing his successes and failures regularly. His book “The Storm Before the Calm” argues that the two big cycles that explain America, will finish together for the first time at the end of this decade.

The 80-year political cycle

The first cycle is political, or more precisely institutional. Each lasts around 80 years and there have been three since the founding of the Republic. The War of Independence, the Civil War and World War II play pivotal roles in creating new cycles, as they do in The Fourth Turning.

Political cycles reflect the balance of power between the branches of federal government and their relations with the 50 states. The tension between them builds to a point where a seismic change ushers in a new period, with a fresh interpretation of the Separation of Powers.

The separation is a deliberate division of responsibility between executive, legislature and judiciary. That is the Presidency, Congress and Supreme Court. The electoral cycles are different for each of them and the top judges have lifetime tenure, easily outlasting those that appoint them.

In the UK, parliament is sovereign, but is controlled by the executive office of Prime Minister, most often the leader of the majority party. With this power, government issues new laws to overcome the resistance of judges. This is why the European courts were at the centre of wrangling over Brexit.

The 50-year economic cycle

Friedman’s second cycle is economic and last around 50 years. The important point is that the President who symbolises change goes against the prevailing beliefs of experts. The leader emerges because of the times, rather than causing them, and rides a popular wave that sweeps through government.

Money supply and tax are important in Friedman’s cycles. Andrew Jackson removed the tariffs that protected northern industries and penalised the agricultural south. He also abandoned Hamilton’s banking arrangements (yes, the ones in the musical) to release money to develop the West.

After the Civil War, Hayes introduced a gold standard to ensure sound money and control of the war debts. The consequent limitations on credit led to the Great Depression, which was relieved by Franklin D Roosevelt’s wealth tax and era of big government.

This lasted until the Reagan tax cuts and deregulations, following the inflation of the 1970s. This had been triggered by the ending of the gold standard, the oil crisis and spending on the Vietnam War.

The economic details are less important than recognising the flip-flopping between economic theories, with high tax and tight money in one era, and lower tax and debt in another. The idea of a debt crisis by the end of the decade is popular among a certain type of economist.

The End of Times

Where Kondratiev, Howe and Friedman theorise from the evidence, Peter Turchin uses data science to extract patterns. He reaches similar conclusions about a coming collapse, albeit he specialises in finding such events. Where the other theorists can be accused of imprecision when defining the timing of cycles, Turchin’s machine learning techniques should avoid that.

Turchin studied hundreds of societies over 10,000 years to uncover why they collapsed. His book “End Times” highlights that while many factors explain individual events, two stand out almost all of the time. These are wealth inequality and the overproduction of elites.

According to Statista, the top 1% in the US own over 30% of the country’s wealth, which is as it was during the Roaring ‘20s. The 1% own one fifth of the wealth of the UK, which is a third of the level of 100 years ago. Wealth inequality is real and particularly acute in the US.

Government financial support for students encourages more people to go to university. This means employers ask for higher qualifications and more students press on with post-graduate degrees. We have a rise in credentialism, without a corresponding rise in jobs worthy of those credentials.

Whether it is jobs in government, the military or the professions, societies that overproduce elites play with fire. Wealth inequality can be addressed, but how to devalue elites? With echoes of the other theories, Turchin notes how the US Civil War dramatically reduced the southern elites, while the Great Depression then the 1970s inflation, wiped out many others.

Yet societies recover from these crisis periods, as Howe and Friedman are quick to stress. Turchin cites examples of successfully reducing inequality through radical change in policies, which proves preferable to the alternative.

The current cycle is ending with talk of a universal basic income, possibly paid in a digital currency controlled by the central bank. The pandemic relief payments were a trial run. While handouts for all may be an anathema to many, it is the many who are proved wrong when cycles turn.

What Comes Next

These theories could all be one. Each describes a different cause, but the pivotal events repeat in the evidence presented in each. If we can show there is an alternative explanation that is both better and does not repeatedly end in conflict, we can sleep a lot easier.

Yet we must not ignore the tendency for humans eventually to resolve differences through war. Increasingly fraught domestic political scenes were often a catalyst for earlier global conflicts. At the very least, we should consider what our future may hold.

Howe expects the current Fourth Turning to last until the early 2030s, when millennials take power and bring rebirth. Friedman predicts the old guard to triumph in the 2024 presidential election, before a younger leader emerges four years later.

Contrary to some media headlines, millennials are no worse off than previous generations. While they own a smaller share of national wealth, they are a smaller share of the population than the Boomers were. On a per person measure, their wealth is similar at the same stage of life.

But this wealth is unequally distributed as never before. Fewer millennials own their homes compared with their parents. A majority favour a universal basic income according to Gallup and three-quarters shop sustainably according to Nielson.

Inequality, sustainability and what to do with all those highly educated graduates are the big political issues of our times. This is as true in China as it is in the West. The solutions can be found in domestic politics. Let’s pray it stays that way.

Simon's most interesting (and worrying) article to date. A must read!

A great, thought-provoking piece that led me to wonder if the delayed development of the prefrontal cortex plays a role in the human tendency to repeat mistakes from history. After all, if we are not able to make sound decisions until our mid-to-late twenties, then we're more likely to make impulsive or emotional choices that could lead to negative consequences.