Environmentalism needs a new narrative

Is achieving Net Zero the challenge of our lifetimes, or lacking in ambition? It’s time to take The Sniff Test

The Overton Window

The Overton Window is a visualisation of the majority opinion on a political issue. A horizontal line represents the range of possible views and the window is where most people sit. Its position moves through time under the influence of those whose views fall outside of the mainstream.

The range of opinions on climate change runs from the deniers of science on one extreme to the de-populationists on the other. Net Zero is in the Overton Window of acceptable opinion. The window has moved steadily towards the de-populationists in recent years, not because their views are any more acceptable, but due to a rising general awareness of environmental issues.

The UK’s change of heart on phasing out of petrol cars is one sign that the trend is over. John Kerry, the US Special Presidential Climate Envoy, now talks of a 2.5 degree warming by the end of the century, when it was 4 or more degrees two years ago. This is science and results will change as our knowledge improves, but it doesn’t fit the narrative of rising panic and is brushed under the carpet.

The way to move the Overton Window is to adopt a view slightly to the left or right of it. You are mainstream enough that you may debate in polite society, while being sufficiently radical to nudge others towards your way of thinking. When you are too wild-eyed and weird your views are ignored.

The Secrets of Marketing Success

A marketing message has four elements. It starts with a problem, proposes a solution, validates it with proof and makes a call to action. Issues are kept separate to avoid confusing the audience and each campaign pushes a single solution. McDonalds advertises Big Macs and McNuggets, using hunger, convenience, value and tastiness to hook our interest. It always uses a single hook and one product per advert.

Your message must be clear and catchy regardless of the complexity of the issue you are addressing. Whether your aim is to win customers or convince governments to pass laws, the rules don’t change. What may change is whether you prioritise market-led solutions or government mandates.

The UK government’s change of heart is framed in the language of consumer choice. Rishi Sunak trusts UK citizens to make the right decision. Despite the rhetoric, the shift reflects that the infrastructure won’t be ready to enforce the policy for at least a decade. A government mandate will fail and it’s better to address that inevitability today.

Net Zero is a catchy slogan that is clear in its purpose. The word net recognises that there will be winners and losers, while zero states the goal of no change. It’s honest, but is it ambitious?

Climate change is a clear message, wherever you stand on the causes. It means rising temperatures due to higher carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere. Humans are accelerating the trend. As far as marketing goes, the problem is clear and credible and backed by public opinion.

The campaign is off to a great start, but it’s downhill from here. Accepting a problem is not the same as paying for it. All campaigns must get to the solution to be successful, rather than repeating the problem over and over. We get it, but what’s the answer.

The Limits of Net Zero

Apple may have had more media acclaim for its recent sustainability video than for the iPhone15. In an entertaining way the company shows how it is meeting its targets, which include carbon neutrality by 2030. Mother Nature is impressed, but Silicon Valley is not.

Apple’s neighbours point out that the company was iconoclastic, pushing the boundaries of what could be achieved. Making a big deal out of achieving Net Zero by 2030 is conformist and the exact opposite of what visionary leaders do.

Meanwhile Microsoft is showing the way, albeit in a low-key message from the Chief Sustainability Officer in the UK. The company is committed to being carbon negative and offsetting all emissions since its founding in 1975.

Microsoft also has messages about water, waste and biodiversity, because you must talk to the whole picture to be taken seriously in the sustainability community. But it knows enough about consumer marketing to focus on the one big message and that is carbon offsetting.

For the environmentalists, the technology industry is not the problem, at least directly. Energy companies, miners and heavy manufacturing are the big carbon emitters and it’s much harder for them to chart a path to net zero. Campaigners are on the look out for back sliding on targets, much as they are with governments, and quickly pounce on any trace of wavering commitment.

It’s an inconvenient truth that Net Zero requires the supply of evermore minerals and materials that are destructive to the environment to extract. Technology companies are huge consumers of these commodities, albeit sufficiently far down their supply chain to allow them to remain darlings of the ESG investing industry. A focus on carbon suits technology companies because it downplays the pollution, waste and loss of natural habitat that is required to transition to solar power and electric vehicles, and to make our handheld devices.

Net Zero has serious flaws. Carbon is only part of the problem, albeit the chosen media message, and how and when to pivot to other issues occupies environmentalists. More importantly, Net Zero is uninspiring, because who leaps out of bed today to deliver no change in ten year’s time.

Microsoft has the right idea, but Apple hogs the headlines, to the detriment of progress.

The Impossibility of Proof

When you are marketing a solution to a problem you must demonstrate how similar customers achieve positive results. This is social validation and why companies have case studies on their websites, newsletters recommend you join thousands of like-minded readers, and beer company adverts feature groups of happy people, rather than loners quaffing Bud while bingeing Netflix.

While we can model Net Zero, we cannot demonstrate that achieving it will be a success. Indeed many campaigners believe we need to go further and remove carbon from the atmosphere, much as Microsoft is promising to do. It’s going to be a bitter pill for people who make sacrifices for Net Zero to find out in 2030 that this is just the beginning of the hair-shirt economics.

This is why climate change needs a new narrative. If net zero emissions is not enough, and carbon is only part of a bigger problem, it’s time to embrace the fact that sustainability is the challenge of the century. You can’t carry a bag-for-life and wear vintage clothing while continuing as normal everywhere else. We have to reinvent almost everything we do.

Another word for this is adaptation. This is an anathema to environmentalists because it accepts that temperatures keep rising and companies will pollute. Adopting this approach takes all the extreme environmental views off the table, including managed population reduction, reduced consumption and nature-first.

Inside the Overton Window it’s hard to see what’s wrong with adaptation, or what is the alternative. If you want to carry public opinion then you need to appeal to a majority of people. Fear of missing out, urgency and scarcity work to move people to make one-off purchases. If you want repeat customers you must inspire, lead and guide: you must create a movement. Just do it.

Nike inspires customers to feel like sports stars, not to be like them. It doesn’t matter if you’re shooting hoops in the park, you still feel like Michael Jordan when wearing his shoes. The validation comes from associating happy, normal people playing basketball with the feeling of Jordan’s jaw-dropping hang time. Association is causality in the minds of consumers where none need exist.

Adaptation is hard. This week Lego abandoned its attempt to use recycled bottles to make bricks because the recycling process generated more emissions than it saved. The company continues to improve the sustainability of its manufacturing and distribution processes, but it’s grand and eye-catching policy has not worked out.

This is reality and reality is a poor marketing message. If anything, the struggles of companies such as Lego reinforce the need for government intervention in the minds of environmentalists. The line hardens at precisely the time the public is prepared to compromise.

Too Many Competing Solutions

The final and most crucial element of a marketing message is the call-to-action. This is what you must do right now to adopt the solution and buy the product. The action may be to click a link to make an impulse buy, or move to the next stage and take a test drive.

The call-to-action is where the Net Zero narrative falls apart and why it needs a refresh. There is absolutely no consensus on what needs to be done.

Climate change researchers fall into three camps. Their academic credentials are reinforced by the ugly phrases used to describe preferred solutions. There are no marketing gurus here.

The most radical position is Degrowth. This means reducing economic activity and particularly consumption in the West, in order to reduce emissions. Next comes Agrowth, which is pursuing sustainable policies regardless of the economic consequences. Finally, there is Green Growth, which accepts the political imperative to keep growing, but with the handbrake of it being sustainable.

Green Growth is a sort of adaptation, although won’t use that word. As a result, researchers are moving away from it towards more radical solutions.

This trend is more pronounced among Western researchers than those in the developing countries and three times more prevalent among social scientists compared with those in Applied and formal sciences.

The Limits of Planetary Boundaries

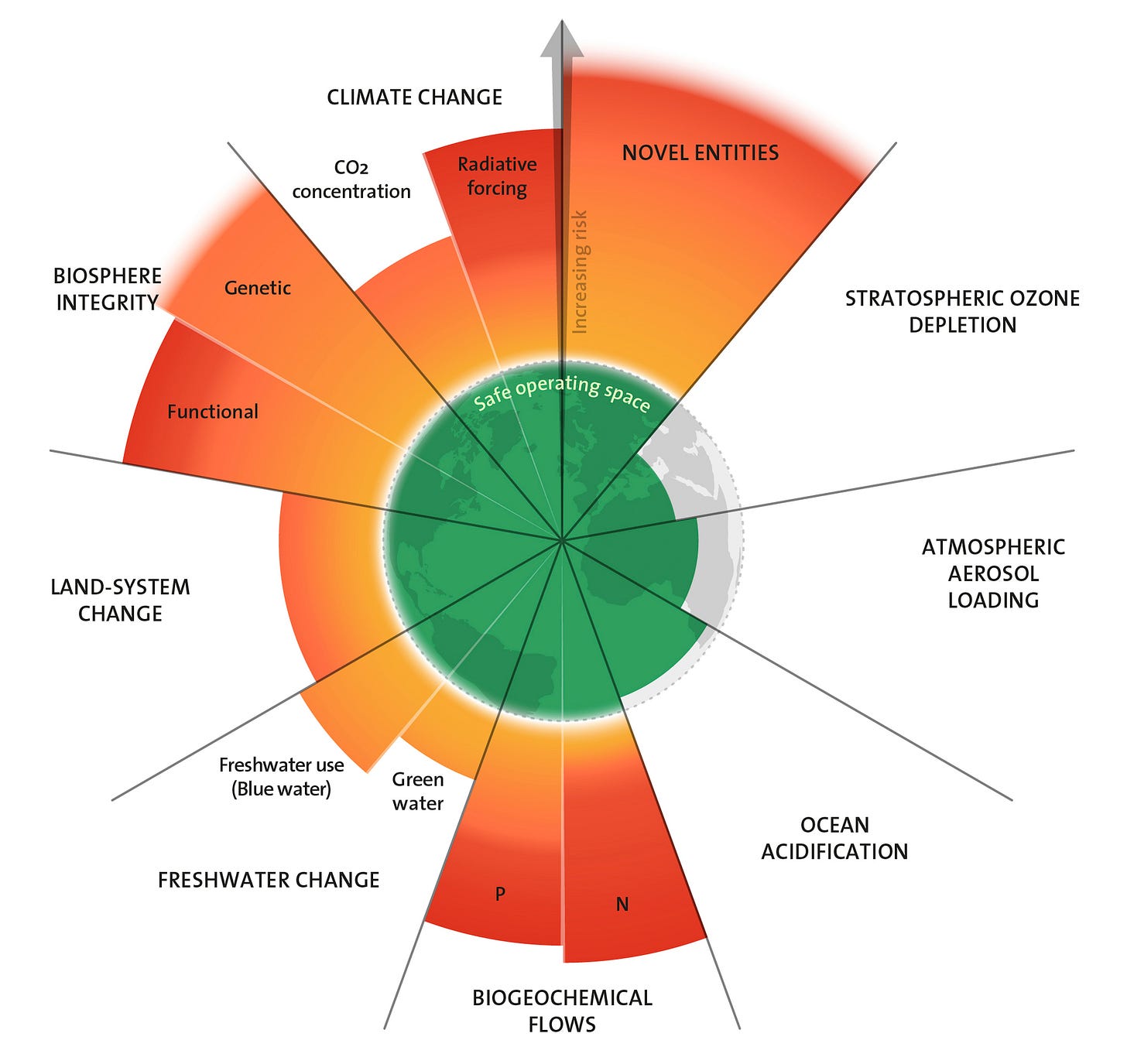

The hardest science in environmentalism is planetary boundaries. To see this, refer to the Green Economy Coalition, which has five principles, four of which are platitudes. But planetary boundaries are bedrock science that tell us we can only go so far and no further when raising carbon concentrations in the atmosphere, polluting rivers and denigrating the soil.

What is the evidence for this? We have models of the future, but their outcomes depend on the inputs and assumptions we use. The big assumption in too many climate models is “at the current rate”. They are a prediction of what happens if nothing changes, but everything changes.

David Deutsch attacks two prevailing environmentalist canons and takes on scientific icons Stephen Hawking and David Attenborough. Deutsch refers to these mistaken core beliefs as The Principle of Mediocrity and Spaceship Earth.

According to Deutsch, the Enlightenment gained traction because it removed humans from the explanations for everything. Most obviously, this included the view that Earth was the centre of the universe. Science overthrew the ignorance of those in political power and paved the way for exponential growth.

This view of human irrelevance was expedient but wrong. When denying the significance of humans, as Hawking appears to do by calling us chemical scum, we deny that we are the only species capable of changing our environment and altering the odds of our survival. To disregard human influence is to deny the essence of humanity.

Deutsch’s second target is Spaceship Earth. This is the idea that we are granted one world and if we stuff it up then it’s game over. We must stop developing now for fear that we have already gone too far. Attenborough made a documentary in 2000 using the abandonment of Easter Island to foreshadow this idea of paradise lost.

There is no Spaceship Earth. Most of us would not survive the upcoming mild UK winter without shelter, heating, clothing and plentiful food. None of this is lying around waiting for us to pick it up. We survive because we take minerals and materials from the Earth and turn them into something useful. The residents of Easter Island died because they repeatedly built statues to their ancestors instead of figuring out how to escape their prison of an island.

Accelerating Adaptation

Peter Diamandis tracks today’s breakthroughs and compares with one hundred years ago. His team has uncovered 12 innovations in 1923. These were important and include frozen food and sound-on-film, but the pace of discovery pales when compared to today. There were 278,000 patents filed last year and while not all are world-changing, the more we try the more likely we are to succeed.

This is the struggle that defines us and what is missing from the climate change narrative that lies outside of the Overton Window.

Too Broad an Aim and Too Narrow a Solution

The marketing of Net Zero is all wrong. It is part of a sustainability message that wants to address everything at once and damn the consequences for economic growth, despite this being the only engine of progress we have ever created.

At the same time Net Zero is too narrow, too restrictive and too dull. No one wants to wait ten years to be in the same place. Give me aspirations, give me adaptation, give me human ingenuity.

There is a place for bans on the most egregious activities that deny the science and turn a blind eye to the damage they cause. There are a lot of them. Most of them no longer take place in the West, which is a political reality that environmentalism ignores.

We must trust the private sector to deliver. Government can help by funding basic research and punish those who refuse to change. But this is not where the sustainability message is heading. Environmentalists should remember their relevance is a direct result of how far outside of the Overton Window they choose to be.