A Roof Over Every Head: The Political Stakes of Solving Britain’s Housing Crisis

The government promises 1.5 million new homes over 5 years. Does it have a hope of delivering? It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

Time for Change

Change! The word leaps from the podium. There are deliberate echoes of Obama’s Hope. The time is now.

Change is how Keir Starmer will be judged. Obama was dragged into the financial crisis from his early days in office. His eight years gave way to Trump.

The King’s Speech laid out 40 bills to bring about change. It reads like a corporate to-do list, with a new process here, and an initiative there. Where things are complicated, we’ll form a committee and get back to you.

The Left screams for 16-year olds to get the vote and child support for large families. The right knows what they mean and points to 1,000 illegals entering the country since Starmer took office. Governing for everybody means being deaf to the extremes.

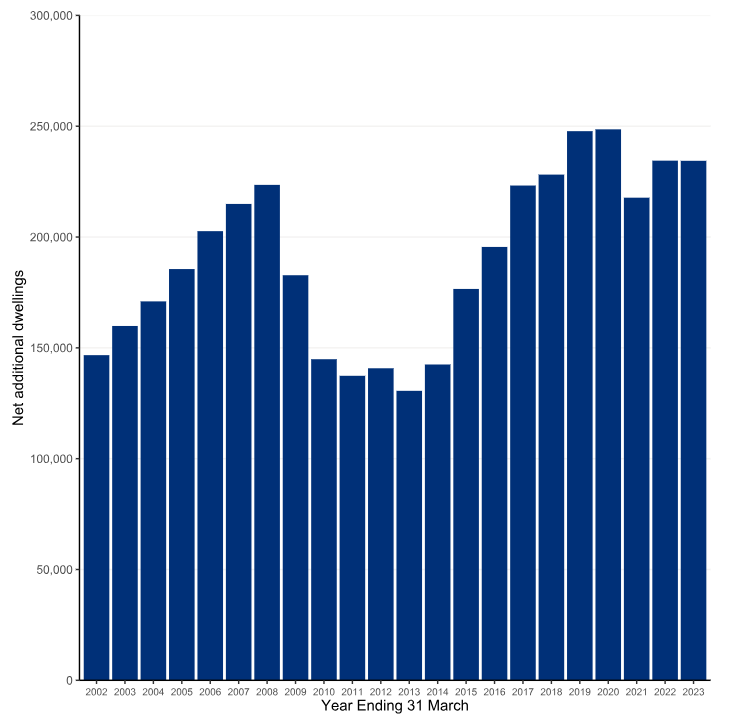

The yardstick for change is housing. 300,000 new homes a year has been the target since 2019. That’s when a Herriot-Watt academic calculated how to meet the demand for 4.75 million new households.

Reaching a target that others couldn’t is the litmus test for Starmerian efficiency. It’s his Olympic gold medal. But there aren’t even 300,000 applications a year to build houses.

Expensive Housing Hurts

High house prices drag on economic activity. They exaggerate inequality and suck investment from more productive industries. It’s an acute problem in the UK where affordability is the lowest since 1876 according to Schroders.

The Centre for Economic Performance says house prices in London are 12x the median income. Homes are the mainstay of retirement savings, part consumer good and part investment. It makes perfect sense for homeowners to fight to preserve their value.

A new development in the neighbourhood may improve the lives of others. But they compete for scarce resources, clog up roads and spoil the view. For many a house is a life’s worth. Build those new homes somewhere else.

Most of the demand for housing is from adults living at home, or sharing accommodation. They put having a family on hold. The population is shrinking as a result.

A house in a major Western city is priced around four times the cost to build. It’s many times this in affluent London boroughs. The gap reflects how hard it is to build new homes and is a deadweight cost for the economy. The residents of those boroughs don’t see it that way, when toasting the rise in home values.

High prices in cities makes it harder for people to move there. For generations, cities have been magnets for bright, young things. Now the talent pool shrinks and the best jobs go to those with family in London.

Less skilled workers are sheep driven further into the hills to find pasture. Then they’re crammed onto trains to bring them back. Many opt for lesser jobs closer to home and services suffer as a result.

The white collar work that London excels in compounds the problem. Companies in software, legal and financial services benefit from being close together. As their wealth grows, they squeeze other industries out. In time this hits the education and health services the well-to-do families demand.

In the 40 years to 2021, house prices in the software mecca of San Francisco rose 932%. New York prices rose 706%. In London, the change was 2,100%.

This is 1,500% faster than wages rose. Over the same 40 years, the price of almost every major consumer durable fell. The housing market is like no other.

Housing is Different

The cure for higher prices is higher prices. Increased demand stimulates supply. The authorities may encourage investment with lower interest rates. Inflation subsides and the times of plenty return.

But lower interest rates jack up house prices. Rental yields become more attractive when deposit rates fall. Investing in homes was made much easier in the mid-1990s. Now 1 in 21 Britons is a landlord. Investors with down payments crowd first-time buyers from the market.

The Conservatives tried subsidising first-time buyers. This made things worse. The House of Lords reports that prices rose by more than the subsidies in areas of highest demand. The unavoidable comparison is with hiked tuition fees straight after students are given more funding. Subsidising demand does not work when the primary problem is supply.

The Centre for Cities compared the rate of new home building in Britain to similar European countries. In the 60 years to 2015, the UK built 4.3 million fewer homes than continental peers. The academic estimate of unmet demands starts to make sense. This is going to take some time. Is it even possible?

Planning Problems

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published a report into housebuilding in February. It concludes that the planning process is unpredictable, time-consuming, expensive, complex and lacks incentives for anyone to meet targets. It then makes a few toothless recommendations to government, including a new quango.

I don’t recall a CMA report that didn’t call for a new regulator. The government plans new powers for Homes England, sweeping changes to the National Planning Policy Framework, and 300 more local planners. Local authorities really need less power.

Around 9% of England is built up. Four times this amount is protected from development. Around 10% is flood plain, which leaves 44% of land to build on.

The law prohibits this happening until a local authority grants permission. The government says localities will have a say in how houses are built, but not how many. They will have mandatory targets. Central government will decide where homes are needed. There is talk of several new towns.

Up to 85% of planning applications are approved. It just takes a while, with large projects lasting more than a year. Planning costs run to hundreds of thousands, even for small developments and the cost is passed on through house prices.

The planners don’t mind, because they have work, power and sizable budgets. The builders don’t mind because high costs keep competition down. They drip feed new supply onto the market to make sure prices keep rising.

Around 30% of new developments is low cost housing. This is sold or rented below market rates and paid for by local authorities. Housebuilders make their money from the remaining homes. They don’t know what these will sell for at first and so release them in stages.

The CMA found no grounds to believe the housing market is uncompetitive. But it did point the finger at the planning process. You cannot build 300,000 homes a year if no one plans to build that many. That is only going to change with more radical policies than are on the table.

Must Try Harder

Reverse approvals are an easy win. Rather than prevent building without permission, allow it unless blocked. With mandatory targets and strict time limits, local authorities would speed up approvals without the need for central oversight. Planners just need to know they can be fired.

This kind of commercialism does not sit well with politicians and civil servants. It all seems a bit nasty and Tory. Let’s stick to fining authorities that don’t meet targets and reducing their allowances. Yet all that does is compound financial problems.

Local authorities must have approved plans for meeting home building targets. Only one third do. They are drowning in bureaucracy and fighting understandable local opposition to development. Promising efficiency by speeding up the process is not going to work. Ripping up the process is required.

Incoming governments tend to act with caution, even after landslides. The political ground is still shifting and they want to see where it comes to rest. The people demand change, but how much? Gently does it at first.

Yet now is the time to act. The government has the necessary majority to overcome dissent. Let’s face facts, increasing housing supply means restricting prices. This threatens big businesses, retirement savers and mortgage debtors. 300,000 new homes a year is a balance between meeting demand and avoiding a price crash.

Taxing Incentives

Tax is the politicians favourite form of social engineering. Only the unreasonable oppose more money for the NHS and a fairer society. New taxes are easier to pass through parliament than grand schemes with clear aims. Let HMRC do the dirty work.

There is green belt land near Barnet in north London listed on Zoopla for £30 million a hectare. It has planning permission, but no obligation to build. Similar land without permission trades closer to £30,000.

Speculators have a huge incentive to buy cheap land and pursue planning permission. The CMA cleared housebuilders of sitting on landbanks, but they own a minority of land. Building could be enforced with rules. An alternative is taxing undeveloped land with planning permission.

Rising house prices are levied through inheritance tax. But it’s a long wait and only a few families are impacted. If people treat housing like an investment, why not tax it as one. Capital gains could be raised on first homes.

This tax is raised on sales. People might choose to stay put and avoid selling. This would increase the need for new housing to meet demand. The reduction in economic and social mobility would be counterproductive.

This is where a wealth tax comes in. The government needs money and there is a lot of it sitting idle in houses. Taxing 1% of wealth a year would hit those who are asset rich and cash poor. They sound like Tories.

Wealth taxes damage retirement savings. As people live longer they run down their assets in later life. They pay for healthcare or help offspring onto the property ladder. Their assets are only temporarily idle.

But if your fundamental belief is that government spends efficiently and for the greater good, these arguments fail. It’s far better to grab the money now and spend it. By the time retirement comes around, we’ll all be richer and have forgotten the taxes. This feels less like change and more like a rehash of the mid 2oth century. The argument goes that past failures weren’t due to poor policies, but because we didn’t tax and spend enough.

There are better solutions than taxes.

The Time is Now

If houses did not rise in price then they would be a less attractive investment. People might invest more in the stock market. Combined with increased access to younger, faster growing companies, Britain’s moribund capital markets may be revitalised.

Government is bad at deciding where people should live. They look at where they are, and not where high prices prevent them being. Target homes are in the wrong places.

London is already a flourishing technology hub. There are universities around the country with expertise in artificial intelligence, clean tech and biochemistry. Rather than new towns plonked far from rail lines, regional development could focus on building centres of excellence around skills that already exist. There is hope that the infrastructure bill may enable this.

Urban sprawl is a result of zoning. People must travel further, which increases costs and pollution. It puts strains on ageing resources. Nationalisation was tried and failed, but this government is about doing things better, so we’ll have another go. Is our current crop of politicians better than those of 50 years ago?

New York City is America’s most densely populated, and has its lowest obesity rate. Manhattan is half as low again and one quarter of the national average. Central Paris is built-up, walkable and a desirable place to live.

Construction costs in Birmingham are half those in Manhattan, but a square metre of office space costs 44% more. Scrapping height limits and view corridors would make many UK cities cheaper and more attractive places to live.

The Green Belt covers 12.4% of Britain. It has no environmental or recreational purpose. It’s sole objective is to stop development. Releasing land around existing stations would be a start.

The UK system grants unique power to incoming governments with large majorities. The only constraint is getting elected next time. This can make politicians too cautious. When you come to office screaming change, you better deliver.