Europe’s Crumbling Consensus Forces a Rethink

The Trump tariffs are causing concern but the problem is 20 years old. It's time to take The Sniff Test.

Divide and Conquer

Donald Trump focuses attention like no other leader. His impending arrival in the White House has governments all over the world considering how they might do a deal to get favourable terms. It’s a text book application of divide and conquer.

Trump’s division of nations coincides with their internal divisions. The longstanding European centrist consensus has broken down, while its proponents use the political structure to cling to power. Musa Al-Gharbi wrote an extensive essay summarising research into why smart, educated and well-to-do people cling to their beliefs for longer than others. But in the face of obdurate electorates change is coming.

Last week the venerable Michel Barnier, who negotiated Brexit on behalf of the EU, became the shortest-lived French Prime Minister of the 5th Republic and the first to be booted out by parliament since 1962. Neighbouring Germany is heading for its own no confidence vote after its ruling coalition, the first three-party government for 60 years, collapsed in November. In South Korea, impeachment proceedings began against the President, after he declared martial law in the country for the first time in over 40 years.

All three countries are beneficiaries of the dollar financial system put in place after World War II. Under this arrangement, the US buys goods from its allies and in return they invest dollars into the US economy. The powerhouses of Europe were rebuilt this way and South Korea made the leap to a developed democracy in similar fashion. Now the threat of Trump tariffs is creating an urgency in all three to have coherent, majority governments in place before the January 20th inauguration.

France’s Peculiar Democracy

I use a simple definition of democracy as the periodic right to reject a government. France is different, because for years elections have been about rejecting the opposition. The rise of the far right, now called the National Rally, has been met with a plea to “Save the Republic” since 2002.

French elections for both president and parliament have two rounds. The assumption is that voters choose who they want in the first round and then block who they don’t in the second. Anyone who gets a majority in round one wins, otherwise there is a run off between the top two candidates. National Rally candidates won the most first rounds in the recent legislative elections but without many majorities. The party’s figurehead Marine Le Pen was defeated in the run-off in the last two presidential elections.

The second round of a presidential election held in the UK tomorrow would be between Farage and Starmer.

Imagine the campaign to keep Farage out. That’s what the last two French presidential elections and the latest parliamentary vote were like.

The vote against National Rally resulted in a majority of left leaning parliamentarians from a variety of parties. President Macron responded by asking the right wing Barnier to form a government. He could not get his austerity budget passed, so he invoked Article 49.3 of the constitution, which allows bills to pass without a vote. This triggered the no confidence vote that ousted him. There cannot be another election until July 2025 and Macron must try again to enforce his centrist agenda on an uncooperative parliament.

A Fragmented Electorate

The government failure in Germany is slow and steady by comparison. As in France, the rise of a populist party of the right has weakened the traditional ruling parties and made it harder to piece together ruling coalitions. No one will work with the Alternative for Germany, which means patching together left and right wing parties who are destined to fall out. The latest government collapsed because two parties wanted more government and one less, which is the divide I described last week.

The now minority government is compelled to hold a no confidence vote and should it lose, has a couple of months to arrange an election. The opposition parties are demanding a vote before Trump comes to office. The bureaucrats who oversee elections resist however, claiming there isn’t enough paper and ink to print ballot papers. This in a nation renowned for efficiency.

South Korea’s president Yoon Suk Yeol was the prosecutor the last time a president was impeached. He elevated members of the New Right Movement to positions of power and expressed sympathy for the last president to impose martial law. The strength of the opposition to him was seen in the news outlets refusing to surrender to military control, street protests and parliament reconvening to overturn the martial law declaration. While it’s worrying that a president would attempt such a move, the speed of his rebuttal shows the health of South Korea’s democracy.

The common theme in these government crises is the fragmentation of the electorate. The UK is similarly fissured, but the first past the post electoral system covers the cracks and hands a large majority to Labour. The common theme in the countries is the rejection of the globalist agenda. People can see this has broken down and are well aware of Trump’s position, but there is a longer-term reason why we’ve lost faith in the old economic order.

As Old as History

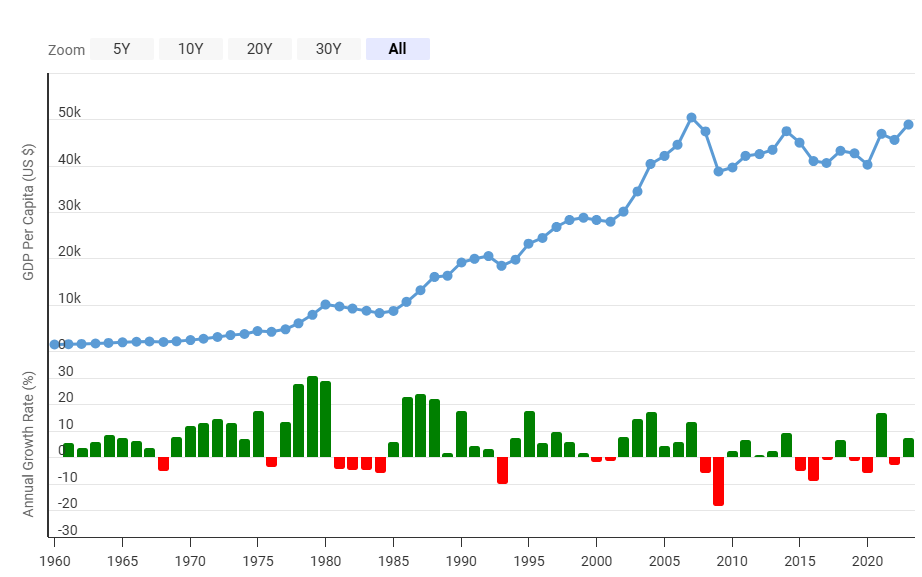

The purpose of government is to make people’s lives better. This chart of the size of the UK economy divided by its population shows how we’ve been progressing.

The blue line shows each person’s share of the economy is about the same as it was 20 years ago. That followed 20 years of strong growth after the mid-eighties recession. Things went wrong in the financial crisis of 2008 and have barely gotten better since.

At the bottom of the chart there are more green bars than red. This is because the economy has grown. The reason is population growth on the back of immigration. Successive governments across Europe have trumpeted economic growth while their electorates have not felt the benefit. The economy grows as immigration rises, and the narrative builds that immigrants are taking our jobs.

In the UK we got UKIP and Reform by way of protest. In France, the National Front became the National Rally. The Germans went for the Greens, who are part of the current government, but now have the AfD on the right as the second most popular party. Support for immigration requires that it go hand-in-hand with the increased wealth of the native population. Unrest over the influence of foreigners is as old as history itself.

Europe’s lost decades

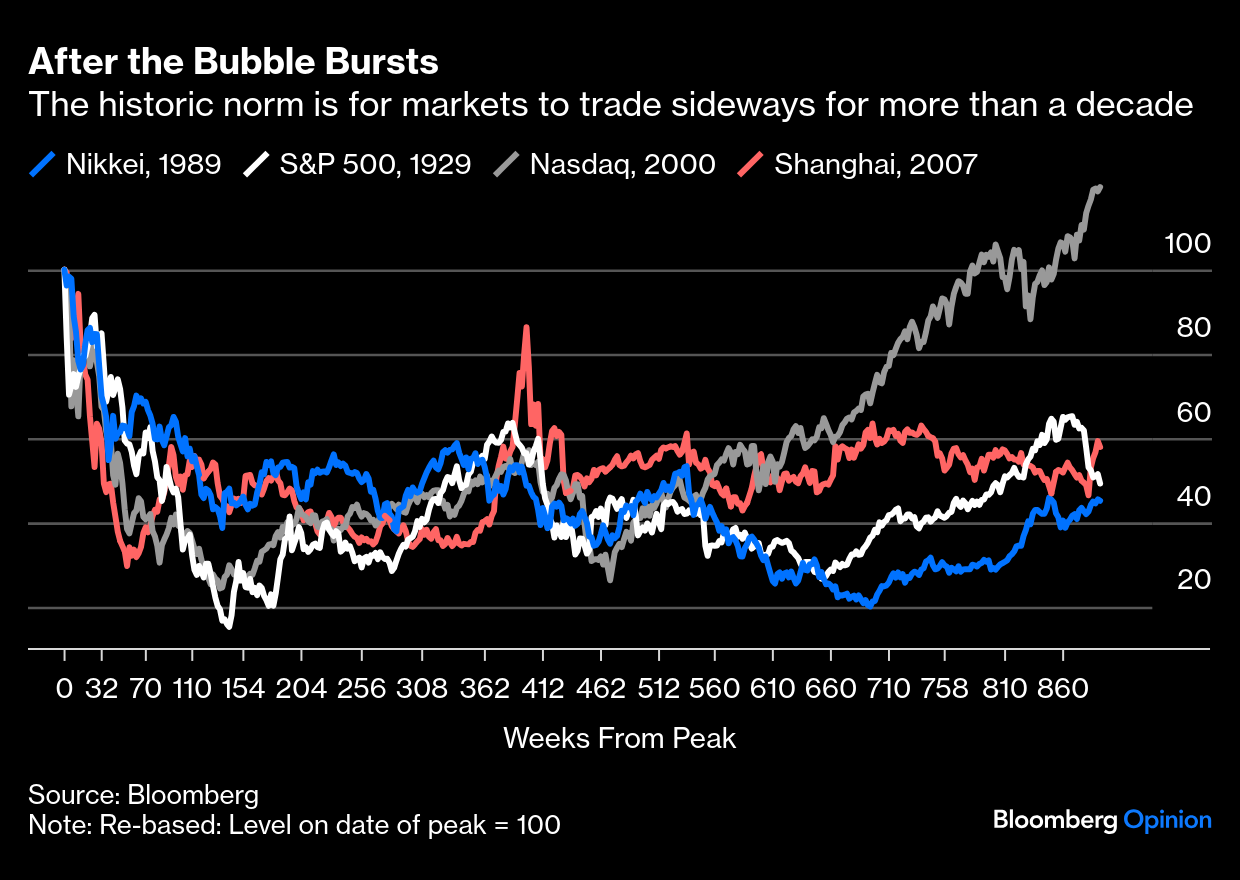

European shares are worth less in dollar terms than 17 years ago. The US boomed over that period. John Authers illustrates that it’s normal for markets to go sideways for years once booms turn to bust. It is the performance of the US that is exceptional.

The outperformance of the US is in large part explained by the superior growth of its company profits.

The speed with which America recovered from the 2008 crisis was down to concerted action to reflate its financial system. Europe waited till 2012 to face its demons but even now lacks the ability to enforce coordinated policy and reform. National rivalries persist and Brexit entrenched a staunch defence of EU structures at a time that was ripe for change.

The dollars that reflated the US combine with continued investment from Europe, the Middle East and Asia into US markets. There is a boom in both public and private companies which many expect to continue. Prequin, the London data company, expects private investments to double to over $20 trillion in the next five years.

Blackrock argues we are in a transformational age, driven by technologies such as AI, rather than a traditional business cycle. American startups take 71 cents of every dollar invested in AI worldwide. The EU president admits that Europe is poor at allowing companies to scale, in large part because it is not a single market.

Blackrock describes the AI transformation as buildout, adoption and transformation, and we’re still in phase one. Spending on AI infrastructure is adding 2% to the US economy through 2030, which is equivalent to an extra year’s growth. This also requires massive data centres and green energy investment. US spending on new factories is almost off the chart.

This does not mean that all is well. America-first is driving emerging market economies away from the dollar, or at least to not recycle dollars through New York. The tit for tat squabbles between the US and China could become more serious and reduced links between the two countries will slow growth in both. But America won the first cold war by outspending the Soviet Union and is determined to win the second outspending China.

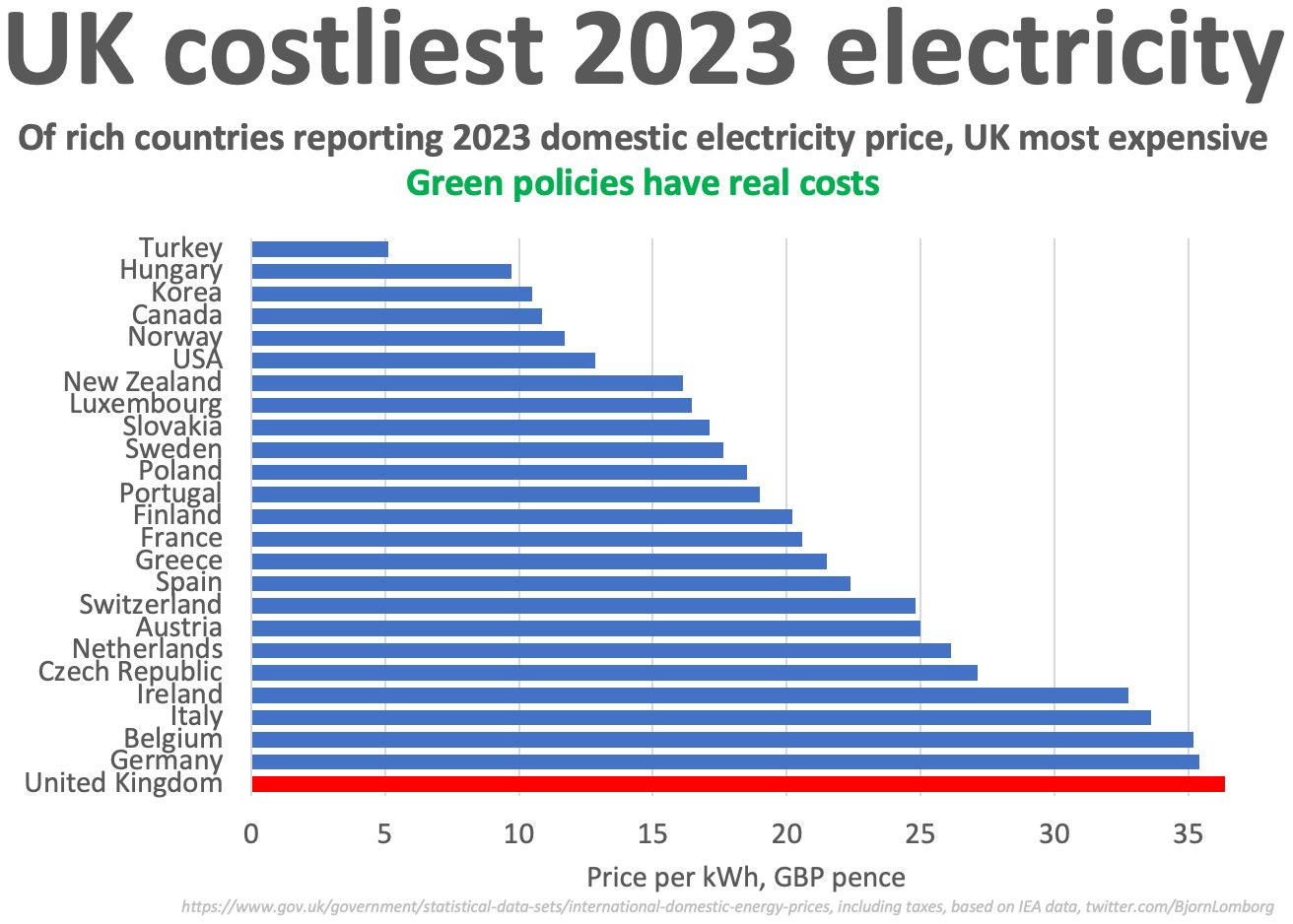

Against this backdrop Europe is a rabbit in the headlights. Its governments restrict AI and the role of US technology companies, but offer nothing in their place. They bet big on the green dream without the raw materials to be anything other than a consumer of other people’s products. Now the dream is dying as the reality of uncontrollable electricity prices dawns on the population.

John Authers ponders whether European shares are about to take off, given the post crisis stagnation eventually ends. Blackrock bets the money continues to flow to the US. Until Europe sorts out its political divisions, the smart move is to follow the money.

An excellent read that pinpoints the vulnerabilities of the EU that a case can be argued was planned by one faction in the US that realised pumping dollars into the Eurozone ad infinitum was unsustainable and likely to destroy the Fed before the ECB.

So Trump 1.0 installed Jerome Powell to prepare the roll out SOFR as the US dollar benchmark, removing control from Europe and the massive offshore 'Eurodollars' pool which was benchmarked by LIBOR. This became nailed down the moment Powell secured his second term in the early Biden administration and then immediately hiked interest rates which has seen a capital outflow from Europe and the UK, and forced the BoE and ECB to buy US Treasuries to maintain an inverse yield curve.

Those who claim the UK left the EU in 2020 should look at the current positions of the BoE and ECB and concede that their monetary policies were nearly perfectly aligned and remain so to this day

https://www.statista.com/statistics/246420/major-foreign-holders-of-us-treasury-debt/

So now with Trump 2.0 due on January 20th, capital is flowing into the USD leaving the UK and EU with a massive position in US Treasuries and depleted FX reserves, a cupboard stripped bare of collateral and a commitment to an energy policy that everyone can see is not worth the hot air Ed Miliband exhales telling anyone left listening about Britain leading the way to net zero

I would think the EU is in the more vulnerable position because it has a fractured bond market whereas the UK can at least use repos to keep its banks liquid even if inflation rises as a result.

So once Trump is inaugerated, how long before the BoE look to do a deal with the Fed for dollar swap lines to provide some much needed dollar liquidity, and with that the UK finally exit the EU ?