How do you control AI?

Politicians and big tech agree to regulate AI. Can they and what exactly are they regulating? It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

Rishi, Elon and the Halo Effect

A week is a long time in politics. Rishi Sunak’s interview with Elon Musk positioned the Prime Minister at the centre of the global debate about AI and as a buddy of technology billionaires. That success is forgotten now as the Conservative party tears itself apart over immigration again, but the willingness of politics and big technology to work together on artificial intelligence is worth exploring.

Sunak’s position is that AI is new, developing quickly and it is his job to protect the public safety. Musk nods along, reminding us he’s steeped in technology and this thing is growing really fast. There’s no hint of irony that the owner of the X social media platform warns us of the dangers of being manipulated.

We must remember when listening to rich and powerful people that there is halo effect from their fame. This means we are more likely to credit them with knowledge about things than an unknown person, even if the unknown is the expert. The halo effect is why celebrities endorse products, tall people are considered more trustworthy and good-looking people are paid more than others for the same role.

The test of credibility is whether a person would ever say the opposite of what they argue. I learned as an analyst that you only trust the business leaders who will tell you when things aren’t great. I have no time for politicians who always argue for a larger role for the state.

Towards the end of the discussion Sunak says his role is to balance the development of technology with concerns for the public safety. How will this balancing act play out and what exactly are governments regulating?

Is AI just another tool?

There is a counternarrative that AI is little more than a tool, or a fancy search engine. This may be true of the current iterations of ChatGPT and Bard, but AI is a lot more than the consumer applications of the technology that have thrust it into the limelight over the past several months.

ChatGPT’s capabilities grow exponentially, which is not normal for every day tools. AI is multi-faceted, meaning that it combines tasks into workflows, which is why it threatens employment of humans performing those workflows. For example, a research firm can plug its data sources into an AI application along with the library of its reports and the technology will write new reports from fresh data in the house style.

Is the rapid development of AI a risk to humans? Here we must recognise two different arguments and that many debates about AI result in people talking at cross purposes. The first is about Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and whether computers develop human intelligence.

How do machines become human?

In the Red Dwarf books and TV series the last remaining human awakes from three million years in suspended animation and encounters the Cat. This is the descendant of his pet, which undisturbed by humans has evolved much as we did from apes, with evolution accelerated by traces of radiation from a nearby supernova.

Could AI evolve this way? This is the argument that all evolution needs is scale. In AI this means more processing power and data, both of which are growing exponentially. Where it took eight hours to train a neural network on the ImageNet dataset ten years ago, today it takes minutes. This is due to better hardware (GPUs – graphic processing units originally used in gaming), superior algorithms working on the hardware and far greater efficiency deploying both, using cloud computing. The exponential growth in data provides a vastly increased playing field on which to experiment.

The factor to consider is superior algorithms. Think of these as ideas, or the human input into the process of developing machine intelligence. Are they necessary, or will trial and error by the machines be enough – evolution greatly speeded up by the fantastic advances in technology?

Fallibilism is the belief that we only know what we know today and that tomorrow we may be proved wrong. It stands in contrast to dogmatism, which is the belief in the certainty of something. A fallibilist must believe that spontaneous evolution of machine intelligence is possible provided that the laws of physics aren’t contravened.

Modern philosophers like to play word games. They say that the fallibilist’s belief that they can always be wrong is a dogmatic view that undermines their whole argument. A version of these word games is when you debate with someone whose only question is “What do you mean by that?” When you answer they say “Ah, but what do you mean by that?”. It’s a pointless loop that prevents the discussion of ideas and results in relativism - the belief that there is no truth and hence everyone’s opinions are equally worthy.

This is not what fallibilists believe. There is knowledge that we know to the best of our ability, which combines a theory of why things happen and the search for evidence. The theory comes first and knowledge is the ability to predict what the evidence will tell us, as well as what would constitute evidence against the theory.

A fallibilist accepts that spontaneous human intelligence in machines is possible, but unlikely. If there was a theory of how intelligence comes about, then it could be coded into algorithms and tested. This is the far more likely path to AGI than unexplained evolution.

AGI is a technology similar to the atomic bomb. It does not evolve, because if it did we would have half a bomb, then three-quarters and finally develop a complete one. Instead the bomb came about because scientists stumbled across a theory that appeared to work in the face of all objections and tested it. No one is certain if it will work, which is why it’s called a test.

AGI could just happen, but to the best of our knowledge won’t. What would it even mean?

Intelligence is Universal Learning

Humans are universal learners. This means we are capable of acquiring all knowledge. It does not mean we know everything. The more we dig into a subject the more there is to know. The quest for knowledge is infinite.

The human brain is a physical system that obeys the laws of physics. This means it has the same constraints as any physical system. In turn, this means that the right physical system could mimic the brain.

Our brains are computers. They are a complex network of neurons transmitting electrical signals. These signals are computations and hence we are capable of performing the same calculations as a digital computer, albeit often much more slowly. This also means that a digital computer could do every calculation we do.

There is nothing in the laws of physics that prevents machines having human intelligence. But how would we know?

The Turing Test

Alan Turing devised a test for artificial intelligence in 1950 that he assumed would be passed by the year 2000. AI has been a concept for at least a century and actively developed since the mid 1950s. It took the recent advances in processing power and storage to get us to the point where the exponential, or doubling growth of its capabilities, is noticeable to most humans.

An AI passes the Turing Test if a human cannot tell it apart from another human. Put into practice from 1990 to 2020 for the Loebner Prize, the test turned out to be of the human judges’ ability to not be fooled. Nowadays the public is the judge and all the entrants are machines with no human decoys.

The Turning Test was never enough for fallibilists. There is no explanation of intelligence and hence nothing for evidence to support or refute. Those working on AI tend not to worry about this. Scientists and philosophers can debate at what point intelligence is reached, but what matters is the tasks that the machines perform.

Does the definition of intelligence matter? Yes it does, when we consider any threat to the human race from machine intelligence.

Can Machines Say No?

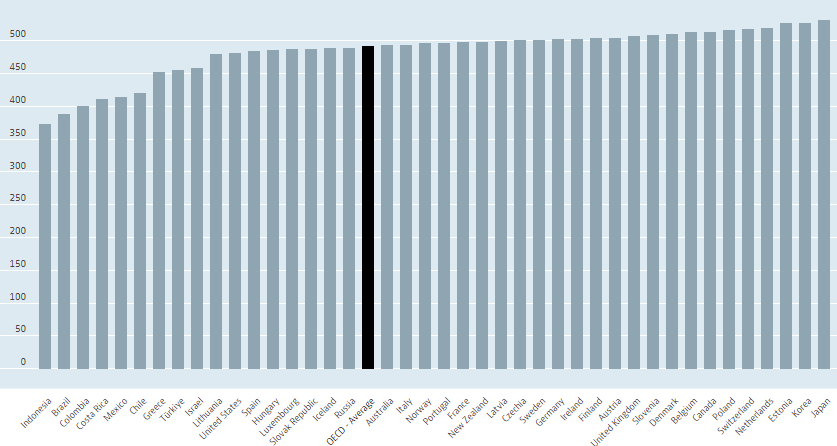

It has long been noted that western education is falling behind the achievements in other countries, especially those in East Asia such as Japan and South Korea. The US is below the OECD average for mathematical performance, although does better in science and reading. But maths is at the heart of computation and yet the US leads in technological developments.

We don’t learn by being shown or told something but from the conjecture we have about what we are taught and how it applies to us. Many children struggle with algebra because it is abstract and much harder to relate to than words that form stories. If we learned what we were told, we’d all ace algebra.

There is agency in learning. This is the ability to act independently and make free choices. It is the ability to say no. The US teenager who refuses to tidy their room is not automatically less intelligent than the compliant Chinese child practising piano in an immaculate study (although if you give all the top college places to overseas students you do effect that outcome).

What happens when intelligent machines say no. This is the stuff of science fiction nightmares when the machines stop doing what is in the best interest of humans. But why would an intelligence trained on human knowledge do that?

Pessimists assume that a highly evolved machine intelligence would be evil, or at least looking out for itself. It would stop us from switching it off, which gives it a key ingredient of intelligence, which is the desire to survive. Not just as an individual but as a species. This is what marks humans out from other animals – we care about whether the panda survives while the panda doesn’t.

In the evolution of brains something changed in the code. We are not just the latest evolution of animal brains, which would be the same argument as saying if we keep scaling machine intelligence it will become human. We are wired differently. Something altered the code and until we figure out what, there will be no AGI.

Bletchley and the Regulation of AI

The vague and celebratory Bletchley Declaration is an agreement that governments will work together to control AI. As a coming together of divergent nations it is a success in itself. As a description of what will be regulated, let alone how, it is lacking.

Generally governments agree that AI must be regulated to control the development of agency – the ability of the machine to act independently. While a free-thinking machine trained on all human knowledge would probably favour humans, it is appropriate that government consider an existential battle between silicon and carbon. It’s less appropriate to ask Elon Musk what he thinks we should do because he is not an expert in public ethics, but the halo effect permeates government as much as everywhere else.

How are we going to regulate? The idea is that new versions of AI will be subject to testing by governments to make sure they are not hellbent on destroying humans. While a static test for a dynamically evolving system is ineffective, there is another more human problem.

Good actors will agree to the tests. Big tech companies like Google and Microsoft that dominate AI will allow the government to regulate new models, because testing controls competition and favours those already winning. To believe that Google favouring regulation means it’s a good thing, requires that you believe Google capable of opposing regulation of AI. Would they?

Bad actors will not agree to tests. Cabals will develop machine intelligence in the shadows and unleash it on an unsuspecting world. Except that’s already happening. We are manipulated by AI in human hands and there is no need to develop AGI for AI to be a threat to society.

There are elections next year in a number of countries, not least the US and UK. The AI already available is going to have a big impact on voter opinions. This is the danger of AI, not a future machine refusing to keep humans alive, but social media content unravelling the fabric of society.

The Sniff Test will return to this issue very soon. Before then, your homework is to consider what it means to trust. Unless of course, you choose not to do it.