How the stock market really works

Raise money with conviction and invest without it. It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

The UK is Boring

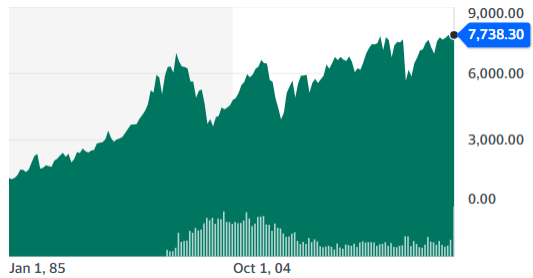

Last week I offered an explanation for why the UK stock market underperforms. My theory is it’s because of unexciting market constituents and pension funds investing overseas. The US, with its Big Tech companies, is particularly attractive. The UK market by contrast is led by oil, drug and food companies, plus a bank.

The UK stock market has risen, just not as much as elsewhere. Shares trend upwards because over time they reflect the value of the companies they represent. This value is the future cash flows those companies will generate. It’s easier for those to rise when there is inflation and economic growth.

This is not how commodities are valued. Oil and gold do not earn cash, but there is demand for both. The price of oil depends on how much is needed, relative to how much is pumped out of the ground. Gold is less useful and its price depends on its supply rising less than the supply of money. This has been the case since the US came off the gold standard in 1971.

Bitcoin does not generate cash. Its value also depends on supply rising less than that of money. Over time, its supply is programmed to dwindle until it stops growing around 2140. Bitcoin is more volatile than gold because it’s a momentum investment. It goes up a lot when times are good and down almost as much when they are not.

Shares also rise with the supply of money. But the assets that companies own reduce in value over time, because of wear and tear and superior alternatives becoming available. Gold remains gold, bitcoin is bitcoin, but companies atrophy.

To avoid this, businesses invest in new assets. They use these to generate higher profits and future cash flows. The combination of rising a little less than inflation and then adding business growth, makes shares a most attractive long term investment.

People are trying hard to use oil and gas more efficiently. The demand for food and banking is steady. We are getting older and need more drugs, but generally the big UK companies are unexciting.

The Technology Conundrum

I also argued last week that AI will either boost the profits of non-technology companies, or they will stop buying it. In the first instance the stock market could continue to rise, while in the second it might not. In either case, the share of total profits earned by technology companies should fall. Those making the components to build AI infrastructure and the infrastructure itself, are most likely to be effected.

I’ve seen reports making similar arguments this week. My old employer Goldman Sachs issued one. It advises investors to look to the companies that will use AI to grow, not just those that build it. The report didn’t dwell on the other argument that AI might not benefit companies. But analysts at investment banks are paid to be optimistic.

So far we’ve looked at the reason why shares go up. This is an argument for buying them and holding on. If you try and trade the twists and turns of the market, you will be beaten by machines. They are faster, programmed with knowledge of market structure, and owned by those with the resources to figure out who is doing what.

Which shares should you own in the long run? It is hard to know which stocks will do best year to year and even more so over a decade. Hence it is popular and cheaper to buy a fund invested across the range of companies in the market. This is common in the US and increasing in Europe.

Venture Capital Winners

The people who get rich from owning companies are those who start them. There is, however, a low success rate in growing small businesses. Even in the exciting world of tech, fewer than 5% of startups rise to a value of more than $50 million. 9 out of ten are out of business within a decade.

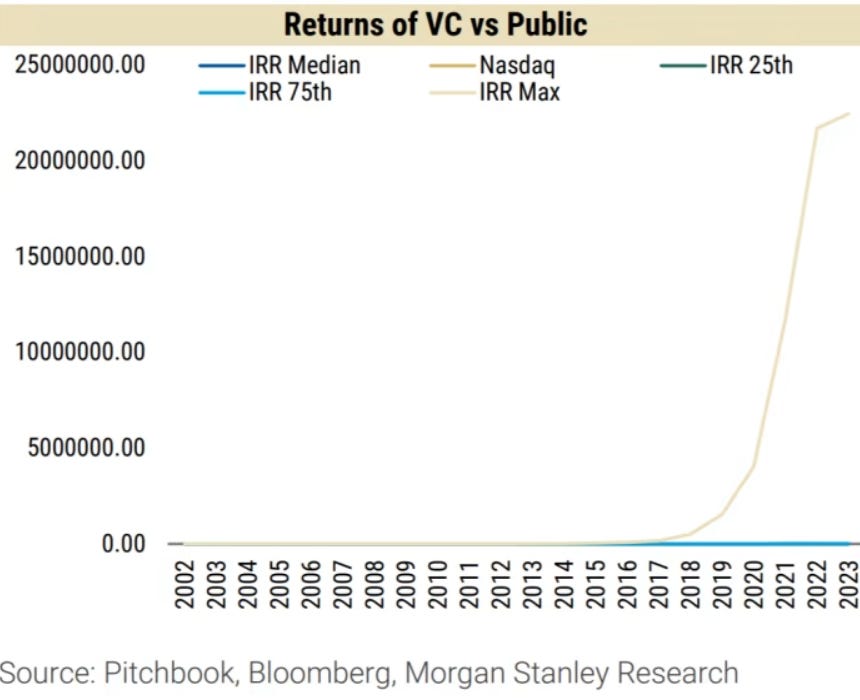

For this reason, venture capital (VC) firms invest in a lot of companies. If one makes it onto the stock market it pays for all those that do not.

Venture capitalists review a lot of companies. On average, they look at 101 ideas for every investment they make. Given the benefits of buying great ideas early, there are many venture capital funds. Only the best provide a better return than the stock market.

The chart shows the performance of venture capital funds versus public stock markets. IRR is internal rate of return and how VC firms measure their profits. The performance of the bottom 75% of VCs is indistinguishable from the stock market. The best venture capitalists have amazing returns in comparison.

Stock Market Winners

The next group that benefits from long-term investing are those buying companies cheaply. The Warren Buffetts and Li Ka-shings of the world made their billions scooping up companies when everyone else was panicking. Li once said he made all his money in four years – the four when there were market crashes.

Value investors try and buy cheap stocks all the time. To win they need other investors to agree with their choices. While Buffett used to play this game, his methods have changed. He buys large stakes directly from troubled companies, such as banks during crises, and pays in cash to get a great deal. Sometimes he buys whole companies. The more money you have, the better the deal you negotiate.

The third beneficiaries from buying and holding are the patient. Because stocks go up through time, if you wait long enough you will make money. How much depends a lot on your age.

My first contributions to a pension were in the early nineties during a recession. Shares have risen a lot since then. If your pension fund is piling into Nvidia today, you may not do as well.

When you retire also matters. As shares are more volatile than other investments, such as government bonds, there is a risk that they are in a slump when you retire. To avoid this, pension fund managers slowly switch investments into cash and bonds as people approach retirement.

The last and least successful buy and hold investors are those that try and choose winning shares. I beat up on value investors because I put them in this category, while they see themselves in a higher one. Few people have superior insight into future share prices and we might call them lucky. After all, if enough people flip coins, someone will throw ten heads in a row.

But what about the people who make fortunes from stock market investing? The hedge fund managers and quant investors that regularly beat the market. What do they do?

Confidence and Conviction

While hedge funds have been around for a long time, they came of age in the early part of the century. The smart analysts I worked with jumped ship from investment banks to hedge funds and bought shares. As hedge funds borrow money as well as invest cash, they supercharge returns, both positive and negative.

There was another recession and stock market slump in the early noughties. Those that bought shares then did very well, at least until the financial crisis. One good year in a hedge fund can set you up for life.

Since the financial crisis it’s been harder to make stellar returns. The price of a lot of assets has risen because their supply increased less than that of money. A rising tide lifted all boats. It got much harder to pick winners and managers lost money trying.

Persuading people to give you large sums of money and pay you excessively to look after it, requires utmost confidence and conviction. You need a strategy that works, but more than that, to convince people that you are the best person to implement it. Just as venture capitalists judge the character of startup founders as much as their idea, hedge fund investors back those with sound maths and bravado.

But the maths only works for so long. Other people copy and the advantage fades. You have to keep tweaking calculations to stay ahead. This is tiring and hard, meaning machines do it better than humans. The single strategy hedge funds shrank.

The other reason that the maths doesn’t last is because it is probabilistic. Say there is a 53% chance of a share price rising based on past experience. This is an observation not an explanation and there is no reason it will hold. Especially over longer time periods.

There are as many theories for share price performance as there are algorithms. Each does something different based on the data used to create them, the assumptions made, the calculations, and the price history examined. As noted last week, a theory that is easy to vary is not an explanation. If I tweak the data and get a different result, then my formula proves nothing.

The Smartest Hedge Funds

The smartest hedge fund managers know this. Hence they bought or built multi-strategy funds. There might be an equity long-short manager picking winners and losers, an arbitrager betting on takeovers, a convertible bond manager harvesting price anomalies, and a macro manager buying whatever takes their fancy. The fund owner rotates the money depending on who is winning month by month.

You need a lot of money to invest in venture capital or hedge funds. The biggest and best choose their investors and prefer very rich people with distant time horizons. The longer you take 2% a year from $50 billion, plus 20% of however much it goes up, the more likely you become richer than your clients.

Most individuals cannot buy these funds because the government says they’re risky. In theory they’re not, because hedging means limiting the downside in stock market crashes. The cost of this is lower returns in raging bull markets. In practice, many single strategy funds failed because they borrowed too much money and ceased to provide hedging.

As pension money has poured into the largest funds, they have had to reduce risk to deliver the steady returns that pensioners require. This makes it safer to borrow and that leverage helps them beat the market. They attract money through the utmost conviction in their strategies, but invest by flipping between them, because sticking with favourites has been shown not to work.

High Risk and Return

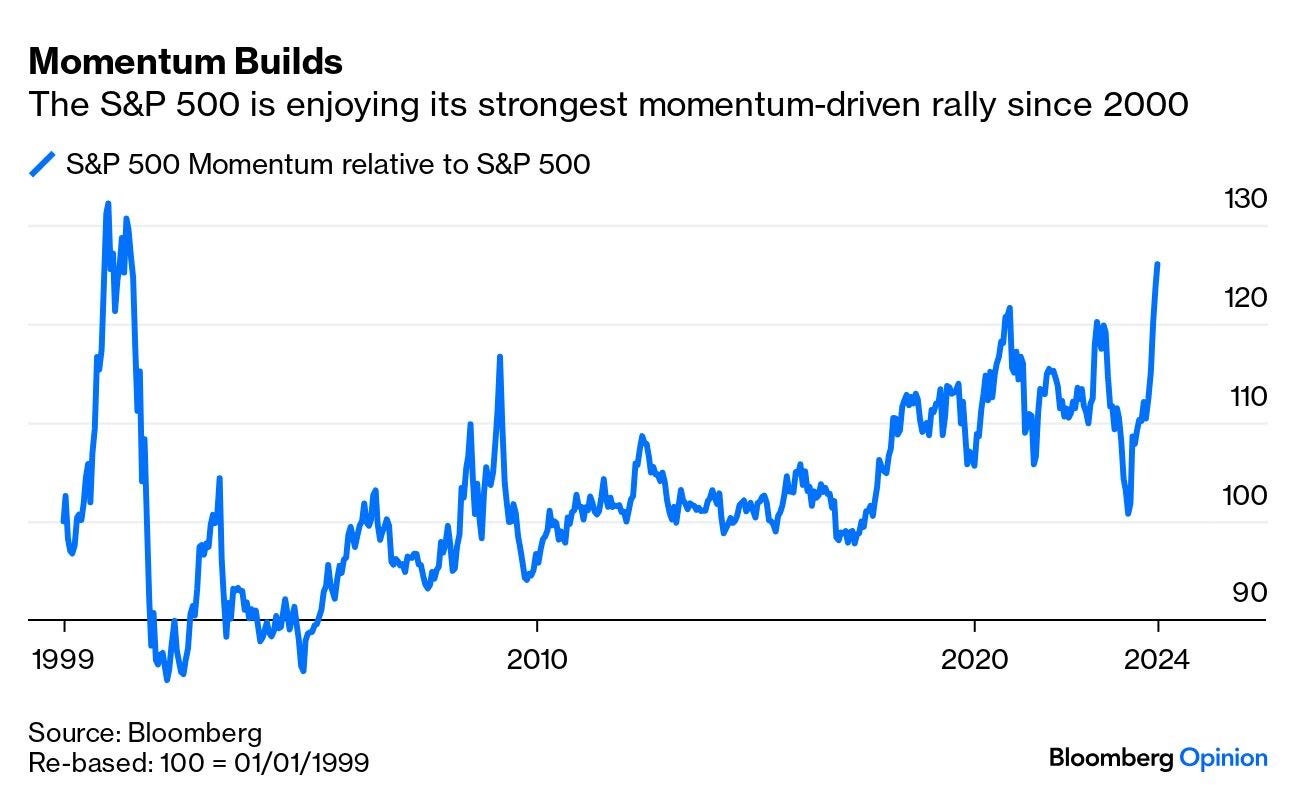

How might Average Joe outperform the stock market? There is a strategy that’s done better than average, in the US at least, by taking a leaf from the hedge fund book. Momentum strategies buy what is working and sell it when it stops going up. There is a bit of maths involved, but not much.

Since 1999, buying momentum in the S&P 500, the index of the largest US shares, has returned 25% more than buying all the S&P 500. A little over a year ago the returns were briefly the same.

Logically, if you only buy the better performers in an index you outperform it. The problem comes when the market goes down.

Momentum works in both directions. When people sell they dump shares in what has gone up the most. That means shares with momentum. Hence the chart shows a lot of ups and downs. If you need to sell during a down period, you could lose money.

I no longer give investment advice and this certainly isn’t it. But when stock markets are rising, buying what rises the most does well. This might work longer term if AI results in stronger profits for non-tech companies. That’s the best chance shares have of rising over the next decade.