On Form and Substance

Is the medium more important than the message? It's time to take The Sniff Test.

From Small to Big

In the mid-sixties Susan Sontag wrote Against Interpretation. She argued that art criticism had become the projection of predetermined ideas onto the content. Consequently, all emphasis was on the meaning of the work and none on its sensuous impact and novelty. All substance and no form.

The essay is reviewed as part of the History of Ideas, currently being rebroadcast on the Past Present Future podcast. The host, David Runciman, argues that great essays talk about small things to tell us about the big.

Sontag may have said that art has less meaning than people think. Can the same be said for the bigger issues of media, finance, politics and war?

The Difficulty of Sharing Ideas

Do you ever sing along to a song only to discover the lyrics are not what you thought. Taylor Swift’s Blank Space has the line “Got a long list of ex-lovers, they’ll tell you I’m insane”. It’s often misheard as a “lot of Starbucks lovers”. Most of Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody is undecipherable.

When singing you are delighting in the form of the song. Often discovering what it is about detracts from the enjoyment. The real lyrics don’t seem as good as the ones you imagined.

Knowledge transfer occurs from a conjecture about what is told, shown, or sung. The misinterpreted lyric is an example of why it is hard to explain to people exactly what you mean.

Sontag saw the contemporary world as one where the physical senses are dulled by mass production and complex interpretation. While written sixty years ago, the same may be said about social media today.

We spend a lot of time worrying about how others interpret what we say. This is a direct response to the free speech police who really mean free interpretation. As in, they are free to interpret what you say as they choose.

Similarly to Sontag’s art critics, people project preconceived opinions onto you based on your age, race, gender, class, assumed wealth and beliefs. OK Boomer.

The Power of Speaking

After the Bali Bombing in 2002, a good friend delivered a powerful eulogy at a service in the Midlands. I have no recollection of what was said, but I remember it as personal, amusing, affectionate and celebratory. That is how the words made me feel.

Neil’s stepfather also spoke. I recall him as angry. He emphasised his message by noting the vicar asked him not to be political, but that he would be anyway. His son had been murdered. I’m still haunted by the mother’s wail as the coffin was lifted one final time.

When we give a presentation our audience forgets half of it within a couple of hours. The next morning three-quarters is gone and a week later only 10% of what we said remains. The leftovers are the memory of the form, how the presentation was made.

In marketing, it’s important to deliver one message at a time. That way you have the best chance of it being what people remember. Deliver a stream of facts and arguments and no one knows what your point is, now or later.

You can also use form. Is there an advert you love to hate? Maybe it’s got a catchy but awful tune, like “Shake ‘N’ Vac”, or a character with an annoying voice. This ad is considered a classic.

Social media creators are advised to adopt a bright colour and use it everywhere. Video makers recommend wearing distinctive headgear or item of clothing. Your favourite popstar probably has a particular look and comedian a catchphrase. This is all form.

In the Public Speakers Academy we’re taught to support our words with body language. Move from left to right as the audience sees the stage when telling a story. Push the palms down to emphasise pain and raise them for pleasure.

The 7:38:55 rule says that 7% of meaning is communicated by speech, 38% by tone of voice and 55% through body language. The form supports the message but unless you make your point very clearly, the form is what is remembered.

Art is communication and Sontag had a point. It’s okay to like art because of how it makes you feel. You don’t need to worry what it means. That’s probably been imagined by a critic anyway.

The Story is Substance

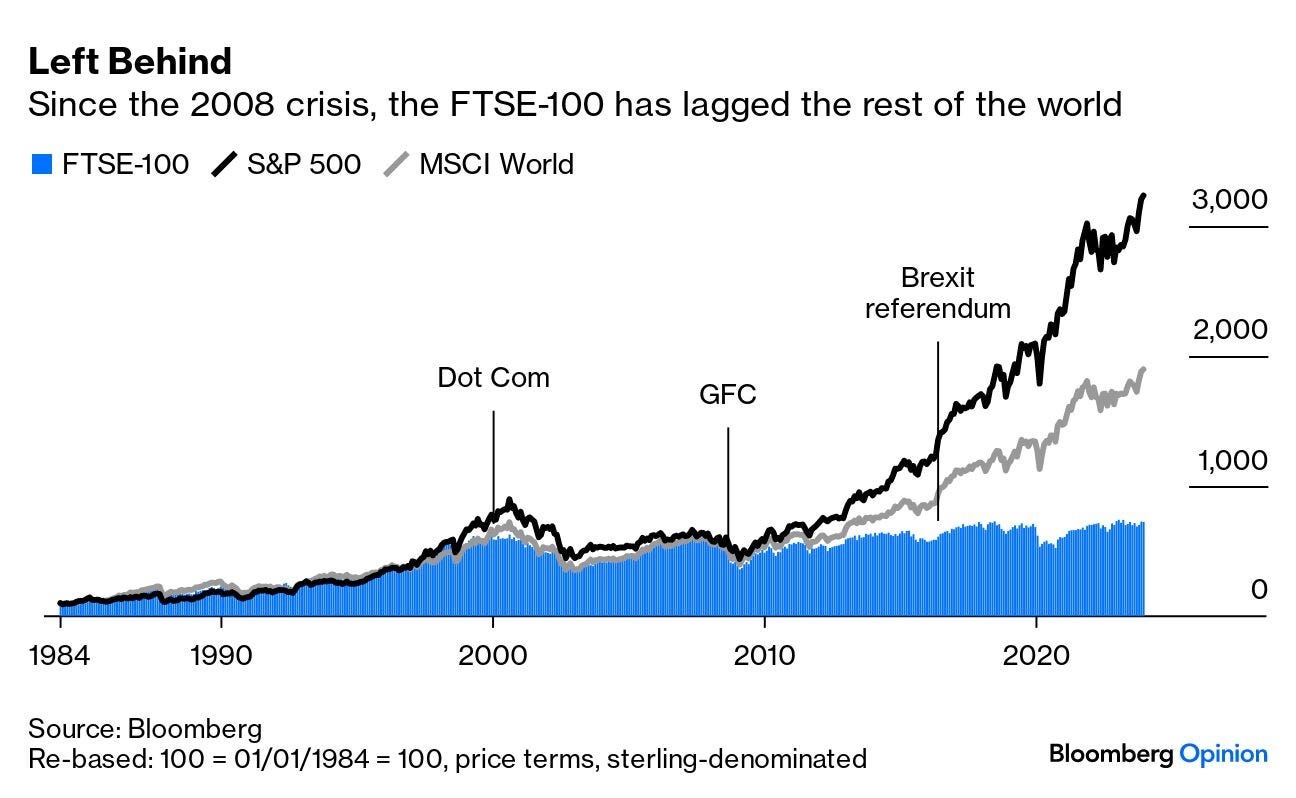

The FTSE 100 index of top UK stocks turns 40 this year. For more than half of its life it kept pace with global stocks, but since the crisis of 2008 it has fallen behind.

The reason for this has substance and is all about technology. The UK has one sizable technology company, RELX (formerly Elsevier-Reed) which is the best performing share over the past 40 years. The UK also has lots of mining companies, but no mines, which do better when there is inflation.

The story of the last four decades is global deflation. Interest rates fell from high levels at the dawn of the ’80s and China became the world’s low cost manufacturing hub. No new technology and overreliance on inflation put paid to the FTSE 100.

This narrative exploded after 2008 as technology became the sole salvation of our economy. Most innovative technology comes from the US where stocks have done best. Just as inflation reared its head and interest rates rose, the new technology of AI burst onto the scene to rescue the narrative.

Story is substance. Critics live for the message in an artwork. If it’s unclear they fall back on preconceptions. Stock market commentary works in a similar way and can overemphasise substance in its search for meaning.

UK pension fund managers responded to the outperformance of the US. They dumped local companies and bought overseas. The reaction is to the narrative of tech dominance and creates a flow that reinforces the trend.

The pension funds also bought lots of government debt. This is about form not substance. Rules, which are the form of investing, require liability matching to prioritise safety first, which means buying investments with steady income to ensure retiring pensioners are paid.

Buying bonds pushes the price up and the yield – the interest rates they pay – down. The lower that income falls, the more bonds must be bought to get the same result. With a finite amount of money to invest, pension managers must get creative.

Derivatives are a way to borrow money when investing. They also make lots of money for investment banks buying and selling them, focusing on the form not the substance of the instrument. Regulatory requirements to generate income and the enthusiasm of banks to invent ways to do this, pushed UK pension schemes off balance.

Imagine you buy a £500,000 house with a £50,000 deposit and £450,000 mortgage. If prices fall 10% your equity is wiped out but the bank remains whole. Similarly, when derivative trades go against you, equity is wiped out but money still owed. You can go bust quickly.

This is what happened in 2022 when Liz Truss decided to boost the economy with unfunded spending. Traders said no and the price of bonds collapsed. UK pension funds owning bonds with borrowed money went bust overnight, necessitating rescue by the Bank of England.

What was supposed to be regulation to make pensions safer had made them riskier. Too great a focus on the form of investment meant losing sight of the substance of retirement saving.

Nationalism and Globalism

Lea Ypi is a regular guest on Past Present Future. She has political and philosophical qualifications up to the eyeballs. She also has one argument.

Politics is a continuous debate about form and substance. What is democracy and the best way of achieving it? Karl Popper defined it as the only form of government that allows institutional improvements without violence and bloodshed. In short, you can kick the rotters out.

This definition has form and substance. The electoral system allows good government to stay in place and bad government to be replaced. This is its form. The substance is institutional improvement and striving for a better outcome.

Ypi sees democracy as dynamic, moving towards a goal. That goal is a fairer world. As referenda among eight billion people are impractical this means greater equality among nations. Her every criticism of western political thought becomes that it is western political thought and therefore not global and not fair.

Wealth is distributed unequally because redistribution stops at national boundaries. Most political thinking does too and therefore is flawed. There is a climate crisis because political systems don’t balance the needs of rich and poor countries. Every problem is scaled up to the international level and the solution is global democracy.

This argument is pure substance. There is no discussion of the form this would take. Unions between countries work like any business partnership or sports team. When the going is good they work well, but when problems arise they fall apart in recrimination and blame. People are more attached to national identity than a concept of fairness and this undermines globalism in all its forms.

Self Defence and Israel in Gaza

Krav Maga is a self defence system that I studied in New York. There are three rules if you are threatened on the street. Firstly, run away and if you cannot then surrender your wallet. If attacked, respond with maximum force for minimal time. Then run away.

People film altercations rather than helping out. They sympathise with the victim but only so far. If you repel an assailant and then turn on them, the crowd turns against you. Videos can be edited to show you as the aggressor.

This seems to be happening to Israel. The longer the fighting in Gaza continues the more sympathy ebbs. Wars start over substance but quickly become about form. How are they fought and who is best equipped.

The attacks on shipping in the Bab el-Mandeb strait are pushing up the cost of goods and energy. This effects Europe and Africa more than the US. The western alliance can be picked apart by a narrative of Israeli cruelty and rising economic costs.

Politics and war are complex and it’s hard to separate substance from form. The US benefits economically from supplying weapons to its allies, but does not want to be drawn into fighting on multiple fronts. It is also engaged in a culture war to which the Gaza narrative is central.

The President of Harvard stood down this week. She lost control of her institution and had to go. The accusations of plagiarism are a smokescreen for academics to oust her on form, while maintaining their own pro-Palestine substance.

Political systems survive when they are adaptable. This means doing what is in the best economic interests of the nation. The substance comes first.

Form is what alters to keep up with technological changes, shifting sentiment among the population and the balance of power in the wider world. Alliances last as long as they are convenient. Democracy the same.

How You’ll Be Remembered

Runciman argues that Sontag walked back from Beyond Interpretation in later life. This might be because she saw it as critics do, as a commentary that worked at the time. It may be because she wanted a legacy as a creator of substance. That’s hard when your message is that too much importance is attached to meaning.

When Sontag died in 2004 the obituaries focused on her substance. The writers of these were attacked for not addressing her sexuality and revealing the nature of her friendship with Annie Leibovitz. The form of her life was titillating while her campaigning was old hat.

Very few of us have a message so strong that it is how we are remembered. Mostly we’re recalled for how we made people feel.