Realpolitik and the Culture Wars

The battle for technological supremacy confines campaigning to campus. It's time to take The Sniff Test.

Tilting at Windmills

Realpolitik prioritises practical and material factors over ideological, moral, or ethical considerations. It stands apart from rights based and similar interpretations of the world.

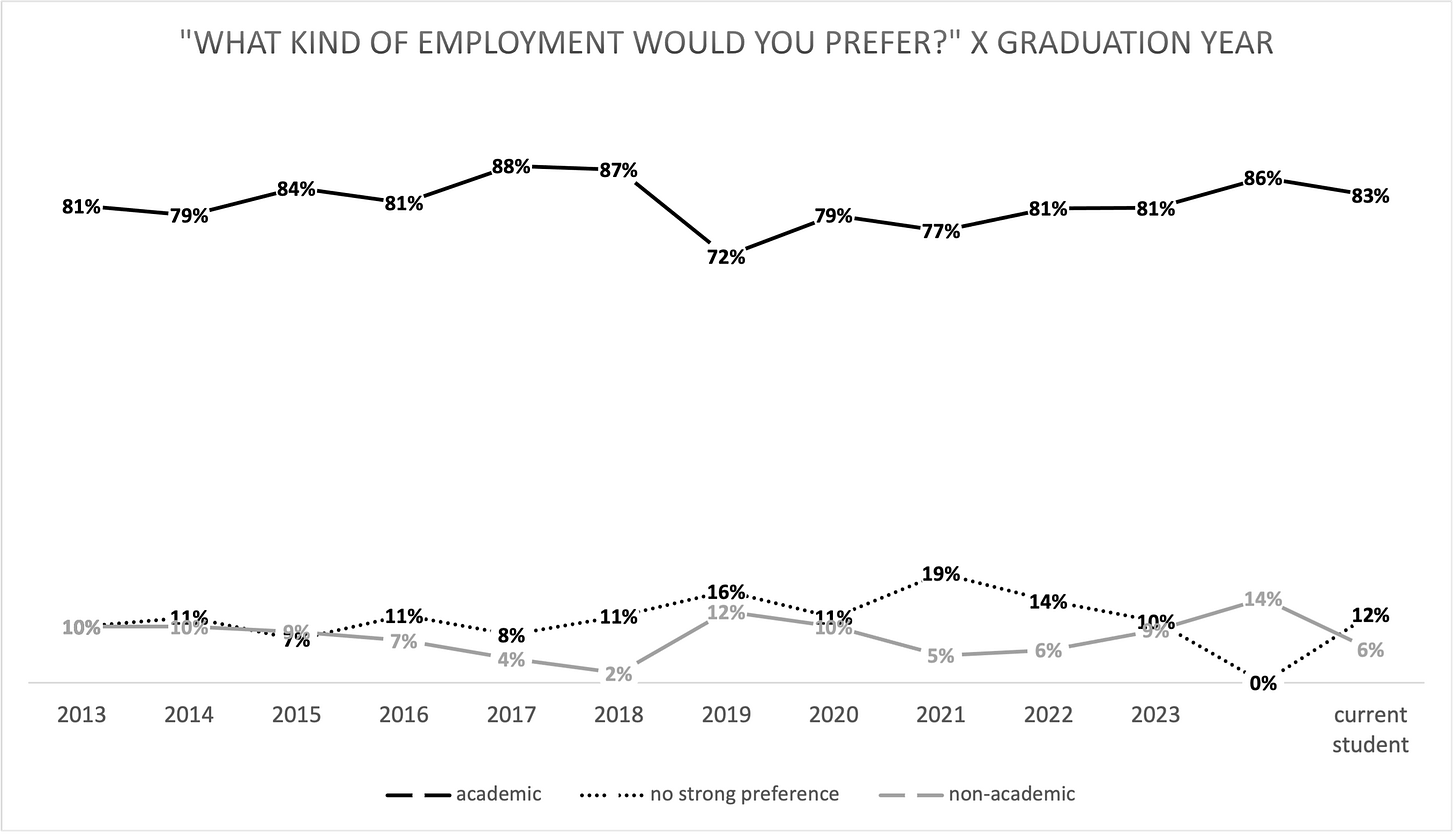

The term dates to 1853 and German politician Ludwig von Rochau. My definition of realpolitik is what happens, rather than what ought to. Students and scholars argue about what’s right, but they don’t change anything. 12% of philosophy PhD’s gets a job outside of academia.

In fact, most PhD’s want to avoid realpolitik altogether.

For many engaged in the campus uprisings, this is a last tilt at a windmill before reality bites. It’s different to 2020 and the height of Covid, when progressives were winning the culture wars. Realpolitik means we’re out of time to indulge ideology.

Slow Burn

Until recently, the culture wars were being fought on the breakout sofas of West Coast technology firms. Tech leaders, led by Brian Armstrong of Coinbase, fought back by returning their companies to being mission-led. This means paying people to leave if they want to use work for political campaigning.

This matters, for the technology industry is crucial in shaping the US role in the world. The message is clear; you may want our armies and navies to protect you, but you’ll definitely want our tech. Europe is struggling with this at a cost to its economy.

Consequently, the US government cannot beat up the tech industry too much. Apple generates $100 billion in cash every year, which is too big a honeypot for serious players to ignore. The March rebound in iPhone shipments following price cuts, indicates the Chinese continue to control US tech, rather than prevent its use. There is too much to lose in tit-for-tat bans.

Economics is always critical to war policy. The trade blockade preventing cotton reaching the UK starved the Confederacy of cash in the US Civil War. The Nazis ran out of oil. Control of the seas was imperative for Britain’s political empire, as it is for the US economic one.

The New Cold War comes after 20 years of global integration. Unpicking supply chains takes years and building semiconductor capacity decades. The latter requires workplace harmony in Arizona. Right now that means US workers doing overtime and Taiwanese migrants taking down naughty calendars. That’s realpolitik in the workplace.

The New Cold War is a slow burn conflict. Technology firms invest to make money and do not overcommit, the way a government might during total war. For the foreseeable future both sides are placing pieces on the board, preparing for battle.

The main Chinese weapon is clean technology. For the US it’s artificial intelligence and the kit to run it. AI requires huge amounts of energy and clean tech is best placed to supply it. Assuming that means harmonious relations ignores reality.

There are ample sceptics of both technologies, but outsized gains require an appetite for risk. That means going all-in and the commitment of Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta and Apple to AI suggests it’s the real thing.

Monopoly Money

The last Monopoly world championship was held in 2015. The winner took home $20,580, the amount of money in a US set. Professional players tend to go deep in debt in a land grab, before horse-trading assets in the middle of the game. It’s a life lesson.

Technology companies don’t need debt to buy influence. But given that every debt is someone else’s asset and much of your spending someone else’s profit, growth of debt boosts the returns from the most in-demand products. The resulting cashflows are fuelling a land grab.

Microsoft leads the way. Its prime asset is the $13 billion invested in OpenAI. The genius is getting more than this back in spending on cloud storage and services. The company has invested $2.9 billion in the cloud and AI in Japan, and $2.2 billion in Malaysia. It has spent $1.7 billion on cloud services, AI and data centres in Indonesia. It made a $1 billion investment in AI through G42 in the UAE.

The company is offering AI skills training for 2.5 million people in ASEAN and aims to make Saudi Arabia a global innovation hub. So do the Saudis, but Microsoft is making sure they look West before East.

Microsoft is making moves rather than disproportionate bets. By comparison Apple’s record breaking $110 billion share buyback looks like an admission of defeat. The company burned $10 billion on automated vehicles before shutting shop and is cozying up to OpenAI and Google. As a small player in cloud services, its AI offering may be to keep iPhones relevant, rather than path-breaking. It’s testing the market with iPads today.

AI is not for everything. Elon Musk raised eyebrows noting that SpaceX and Starlink barely use it. At the same time his xAI startup has received an $18 billion valuation and will work closely with Twitter and Tesla. Let’s hope this is not another technology whose main purpose is to distract us from reality.

The US land grab takes advantage of its technological lead. It also counters China’s advantage in data and labour as a result of its large population. This follows a tried and tested US model of owning the customer, where margins are fattest, rather than the supply chain. China’s land grab here is decades old.

Where China Leads

On top of direct investments in AI and related services, Microsoft announced support for 10.5 gigawatts of renewable energy supply. This is around half of California’s renewable capacity in 2022 and is an international investment to supply data centres. Microsoft opens a new one every three days.

Whether this reduces Chinese influence or enhances it remains to be seen. Microsoft’s commitment is through to 2030 and part of its net zero pledge. The cost and supply chain depend on what type of renewables.

Technology companies are globalist at heart. Open borders, free trade and international peace are preferred. But the bosses are realistic. They send their capital where it’s treated best and the recriminations least.

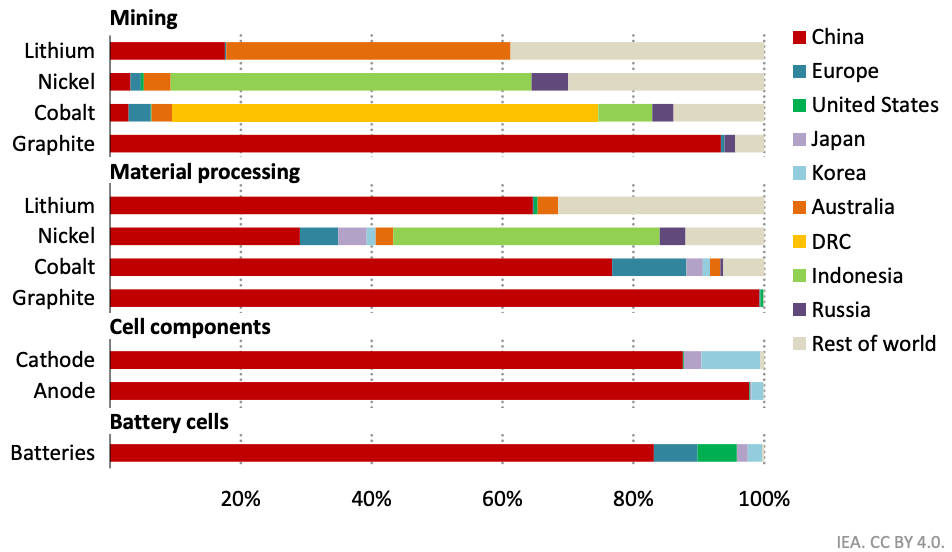

Climate campaigners at Ember report 30% of global electricity was produced by renewables in 2023. The practicality of this depends on battery technology and the ability to store power for when it is needed. This chart of the key elements of the battery supply chain, illustrates China’s lead from mining, through processing to finished products.

China accounts for 70% of world solar panel production. The US and Europe say it dumps overproduction on them and stifles domestic alternatives. China says it meets global demand.

Nuclear is an alternative to solar but Russia controls over 40% of enriched uranium. The Middle East satisfies around one third of global oil demand, restraining production to keep prices high. This allows US shale companies to invest in the technology to drive down extraction costs.

The 1970s deal whereby the US bought Middle East oil provided trade was in dollars is unravelling. The US is less dependent on this oil and other buyers want alternatives to the dollar. The continued strength of the currency against major rivals is creating confusion and concern in financial markets.

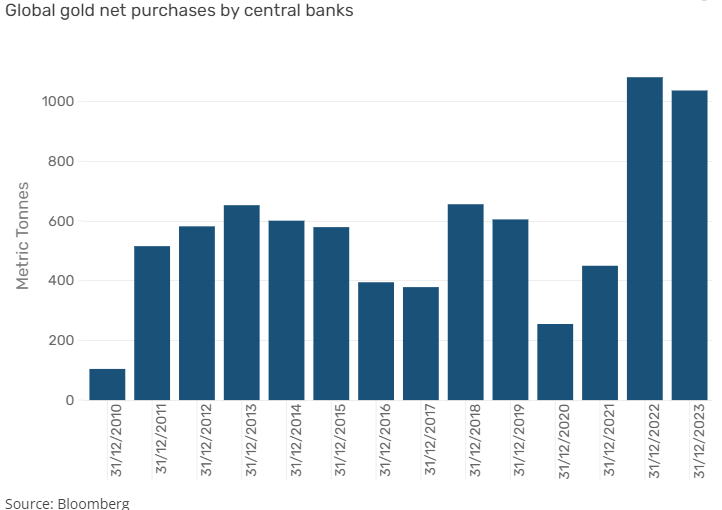

One way to undo dollar dominance is reducing its share of foreign exchange reserves. These are the rainy day funds countries maintain to cover the cost of imports. There is noticeable recent enthusiasm for holding gold.

We are a long way from the end of dollar dominance. We are a long way from a hot war. But the seeds of both are being sown. Hence US public and private sector efforts to shore up alliances and create new ones with the promise of economic prosperity.

Food Security

Lack of food accelerates political change. Starvation is the stuff of revolution and mass migration. The top 10 grain producers supply over 80% of exports of wheat, corn and soybean. Maintaining trade matters and wheat supply is an important element of the Ukraine war.

The US has long monopolised the supply of corn to Mexico. It’s one of several ways it keeps its neighbour in place. The US buys a lot more from Mexico since embargoing Chinese goods. At the same time exports from China to Mexico are blossoming.

This shows the world is not ready to polarise. A weather-related poor crop is forcing coffee prices up, but so is newfound demand in China. Consumer tastes continue to globalise and create natural resistance to delinking of economic systems. It’s hard to imagine US consumers weaning themselves off Chinese goods. It’s even harder to imagine them happy with a shortage of fresh fish, fruit and vegetables, which are the largest food imports.

Europe’s Privacy Problem

Europe has most to gain from international harmony. It is the battlefield of global powers and needs to import technology from both East and West. This is why Macron hosted Xi Jinpeng this week with the head of the EU Commission, Ursula von der Leyden.

There are local difficulties to overcome. Europe is investigating Chinese electric vehicles in a well-worn protectionist policy to help its car industry. French brandy is under investigation in China. Macron gifted Xi bottles of Henessey and Remi Martin cognac.

Von der Leyden noted the uneven playing field created by Chinese state subsidies for industry. Much as the US public and private sector invest internationally together, state controlled companies do the Chinese government’s bidding, including hoovering up global resources. Nothing is going to change there.

Europe does have one important export. Xi confirmed an order for 50 Airbus planes during the visit. He is not going to buy Boeings. The trans-Atlantic aerospace giants constantly sue each other over illegal government subsidies.

The Economist celebrated that Europe had 1,000 more startups than America in the first nine months of 2023. This ignores the size of the companies and the strength of support communities. The top-ranked startup city in continental Europe is Berlin, which places 20th worldwide.

The EU does not have a standard legal entity structure, which hampers the creation of a continental financial centre. With less money raised and a lower price when selling companies, Europe’s startups must pay higher salaries to attract talent. Yet with more money and a higher standard of living, US startups pay more. Global talent continues to flock there.

The lack of a unified legal system prevents Europe following the US attacks on TikTok’s owner ByteDance. Meanwhile it uses competition policy to investigate and fine US tech companies. Countries such as Italy pass laws to slow AI adoption. The US is not impressed.

The biggest constraint on European technology remains the GDPR protecting personal privacy. Since its introduction in 2016, EU companies have reduced data storage by 26% and processing by 15%, relative to similar US firms. The regulations have added 20% to the cost of data according to the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The European Center for Digital Rights is suing OpenAI for violations of GDPR. US politicians and tech bros protest. Data is the lifeblood of AI and Europe is digging a hole that no amount of Economist propaganda will reverse.

The Boys are Back

The title tech bros is used by the media as a term of abuse. This is despite studious geeks being the opposite of the Animal House frat boys the phrase represents. The campus bros are back, breaking up pro-Palestine protests to protect the flag, cheered on by a majority.

Commentators note this is a standoff between male and female dominated groups. The culture wars are about emasculation to dismantle systemic bias. This ideology is meeting realpolitik.