The Case for Community Parliaments

Machiavelli's take on gay rights. Should there be a women-only assembly? It's time to take The Sniff Test.

Positive and negative liberty

Negative liberty is the freedom to pursue your life unimpeded. It includes the rights to the fruits of your labour and is associated with individualism.

In contrast, positive liberty requires outside help. People lack the resources and opportunities to be free and the collective supports them. This is the justification for taxing some individuals and redistributing the money to others.

Machiavelli is best known for advice to sovereign rulers about how to secure their authority. The word Machiavellian implies a ruthless pursuit of power. The man himself preferred a republican form of government.

A sovereign can rule only by disarming the people. Internal security is the most an unelected government can offer them. Machiavelli worried that an unarmed populace cannot protect itself and the state would be reliant on foreign mercenaries. A modern parallel might be a European NATO member.

The sovereign and elites do not protect liberty. With a monopoly on power they neither need nor value it. Consequently, the people are never free.

People value freedom and protect it through a simple motivation. They cannot ensure their own freedom and so act to protect everyone’s. You are supportive of an unbiased jury system if you worry you might need it one day.

Machiavelli understood that there was a permanent tension between elites and the people in a republic. He considered this necessary because in any society there is always an uneven distribution of resources. The challenge is to ensure the people have a fair hearing.

This is the principle of parliament. Debate is the best way to resolve differences, because of the people’s ability to choose the public good. The masses are persuaded against bad policy by gifted orators who show them their best interests. This means the protection of individuals, because people live with the risk of being singled out.

Security and Freedom

There is a conflict between security and freedom. The former is the status quo and an absence of change. The latter is uncertain but filled with potential. Every law passed may restrict opportunity and must be reviewed in the light of this risk.

A sovereign is inflexible. However open and public spirited, they are constrained by tradition and the limits of a single point of view. They struggle to adapt. The advantage of a republic is that leaders change to fit circumstances.

Geopolitician George Friedman argues that politics is shaped by the times. Rather than great leaders bringing change and progress, an appropriate person rises to the occasion, often after a few others have failed. The UK has cycled through prime ministers seeking one who might be up to the job.

Unelected Elites

How did we get from Machiavelli’s idea of a republic producing the leaders it needs, to unelected leaders across the UK? Why do we have two presidential candidates that few favour and a quarter of 18-29 year olds reject?

One reason is that political parties are elites. Membership to the club provides a degree of security that allows the pursuit of personal ends. Over time, what a party stands for drifts away from the beliefs of its supporters.

This is now acute. The Conservatives appear resigned to losing the election and leaders are purging traditional elements through control of the candidate list. Those overlooked claim that promoting diversity is valued more highly than policies the electorate cares about.

In the US, changes to party voting rules make it easier for well known and funded candidates to win primaries. This avoids bitter party infighting and preserves political war chests for the main campaign. The effect is to stifle debate and promote elite interests.

Elites are subject to capture. The concentration of authority allows vested interests to influence policy. Union representatives no longer debate in parliament, but rather use their control over funds and votes to direct politicians. This pales beside the corporate interests that infiltrate every element of the ruling elite.

When Friedman argues that the age of experts is ending, it is the back door lobbies and consultants that go first. Politicians in the next decade will not hide behind the opinions of advisers. Rather they will exercise the generalist skills of deciding between competing claims. We’re not there yet.

Special Interests

The most influential political movements of recent times are special interests. Not necessarily single issues, but causes where all policies are viewed through one lens. Brexit, environmentalism and gender rights are prime examples.

All three seek institutional change. Brexit was about which parliament was sovereign and London is closer than Brussels and the capitals that control it. The opposition was from the why-rock-the-boat well-off and those that do not believe Westminster represents them.

Environmentalism and gender rights are about a different change. Like Brexit, no one knows what Net Zero looks like, but it involves banning a lot without much to replace it. Gender rights are about equality, which is different from liberation.

Subsidiarity is the idea that politics is pushed down to the most appropriate level. A new flower bed for the local church is a parish matter, street lighting the responsibility of the council and national defence relies on the state. It seems sensible, which means there’s a catch. This is The Sniff Test.

Devolution sought subsidiarity and to release tension in the independence debates. The problem is matching income and expenses. Central government does not handover tax-raising power, meaning all local levies are additional burdens.

7% of UK taxes are local. Westminster funds around a quarter of spending, mostly financed by taking half of locally collected business rates. This circular flow is supposed to adjust for property prices. In reality, it’s to stop anti-capitalist politicians trashing the economy.

The lack of financial clout may explain the low quality of local politicians. Both those for and against devolution saw it as a stepping stone to independence. It had the opposite effect by revealing who ends up in charge.

Beyond the Law

Equal rights movements, such as gay and gender rights, seek recognition under current laws. Gay marriage was a significant step. Yet marriage is what women’s liberation fought against and its biggest victory was divorce. Liberation movements want laws replaced and new power relationships enforced. This undermines the case for devolution.

Machiavelli noted the elites were well organised while the people were not. Today elite power centralises in the World Economic Forum, Central Banks, the EU and government lobbies. There are no equivalents for ordinary folk.

Parliament is for the people. At first this was to fight oppression and alleviate poverty. When this is done politicians move to new and more personal issues. There is no one to speak for the poor.

What issues would a parliament of the poor debate? There is a similar question about devolution and what is a Scottish issue. Scots get two bites at the cherry by being represented on some issues at national and country level.

The women’s liberation movement includes calls for a women-only parliament. If both sexes are equal before the law then there are no women-only issues to debate. Hence liberation is about recognising inequality beyond the law. For example, women may receive equal pay for equal work, but still be oppressed at home.

Lea Ipi is professor of political theory at the London School of Economics. She identifies as a Kantian Marxist and is a member of the Labour Party. Her major beefs are with liberalism and capitalism.

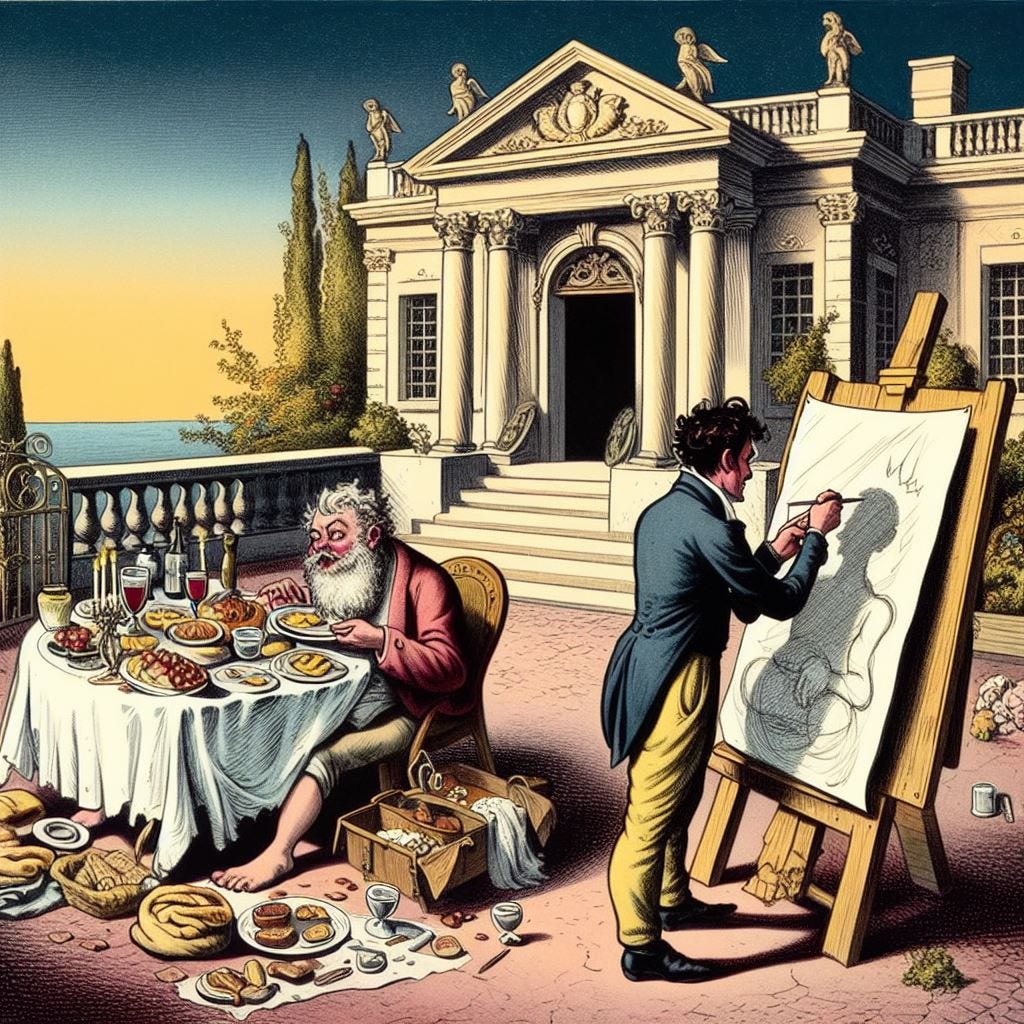

By Kantian she means Kant’s view that humans are moral agents and we relate to each other as ends in ourselves. By contrast people are unfree under capitalism because they are units of production or sales. I ask would you rather be a rich philistine or a poor artist?

Ipi believes the left is an internationalist movement and all solutions that stop at national borders are flawed. Women’s liberation, for example, frees middle class Western women to work, because immigrant female labour watches their children.

The solution is state care of children, but by who? 86% of UK primary school teachers are female and 76% at all ages. As in the NHS, white British people are over-represented. It seems women look after the kids regardless. Liberation looks like environmentalism in that it’s against more than it’s for.

Church and State

If regions and genders have their own parliaments, what about religions? There is no separation of Church and State in the UK, unlike the US, which is more religious. 20% of Americans with no religion pray daily compared with only 6% of the UK’s Christians.

The challenge is that religions recognise a higher authority than the state. There is no liberationist zeal to extend its reach. There is also no debate about the best outcome and no need for a parliament. But there must be courts to enforce religious laws determined by unelected leaders.

Sharia law has been recognised in the UK since 1982, but has no legal standing and is only for civil issues. Acceptance is voluntary to the degree that peer pressure is optional. If your support system rejects you because you don’t accept its teachings, there are few places to turn.

Form and Substance

Minority rights are mainstream because the left has abandoned its opposition to capitalism. The difference in economics between the UK’s two main parties is a marginal debate about the tax burden. The left needs a rallying cry and minority rights are perfect. The campus protests in the US suggest something similar.

Devolution was recognition of the rights of minorities in an attempt to quieten dissent. It’s a fix in form for an issue of substance. Money is the answer that will not be given. Governments survive because of tax-raising power and a monopoly on violence. Give up either and lose the other. Then there’s nothing.

Some minorities are content with recognition. The gay lobby is one. A study suggests gay men are paid 5% less than heterosexual in the UK, while lesbians are paid 7% more than straight women. There is no equal pay for equal work issue here. Financial comfort douses the desire to fight.

Other minorities desire institutional change. This includes nationalists, liberationists and religious groups. This is a debate about where rights come from. Democracies based on one voice, one vote cannot afford positive discrimination that undermines this principle.

The Silent Majority

It is much easier to be against than for something. Minority parliaments might ban drinking alcohol but must enforce it. London prevents drinking on the tube because the police report to City Hall. It’s hard to see a parliament of the poor, of women, or LGBTQIA+ having an army.

The politics of cause plays an important role uniting opposition to government. These coalitions breakdown when asked to be for rather than against. The marriage of convenience between Scottish nationalists and Greens is over, while gay and religious groups will fight forever.

The right often claims to speak for a silent majority. This is the reasonably well off who won’t rock the boat. They are why Cameron thought he’d defeat Brexit. The problem of silence is no one listens, while the people’s leaders assumed they’d win the debate.

As Machiavelli said, a vested interest in the public good is why only the people may be trusted to deliver it. He meant all the people rather than a minority.