The European Electorate’s Lean Towards Conservatism

What EU parliamentary elections tell us about upcoming votes. It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

Macron Tests a Theory

European parliamentary elections are a pressure release valve. Electorates are more inclined to protest national policies by highlighting single issues. Yet the majority vote as always and once back in the national arena, politics returns to issues of individual well-being and government competence.

President Macron is testing this theory. He called a rematch after his Renaissance party took a beating at the hands of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National. His presidency is not on the line, but his ability to govern in its final three years is.

There are two distinct lenses through which to view last weekend’s EU parliamentary elections. These are media and markets. One is calming down while the other heats up.

A swing to the right was expected. Open borders and the costs of Net Zero are concerns across the continent. This did not stop the media raising the alarm about the rise of the right at the first exit polls. They calmed down once it was clear the ruling coalition remains in place.

Meanwhile financial markets shrugged off the expected results. Then Macron called an election in France. Markets abhor uncertainty and the President created a load. The French bond market, which is supposed to be twinned with Germany, started acting like Greece and Italy.

This continues a trend of adverse market reactions to elections this year. Mexican markets reflect suspicions about constitutional changes. The ANC lost its majority in South Africa and doubts about its future partners overhang the currency. The biggest surprise was Modi’s BJP losing its majority in India after predicting big gains. The stock market fell after the partial rehabilitation of the Congress Party.

The US stock market has had its best ever start to an election year. Trump leads the polls in another apparent rightward shift. Only the UK bucks the trend. What is going on?

The Centre Holds

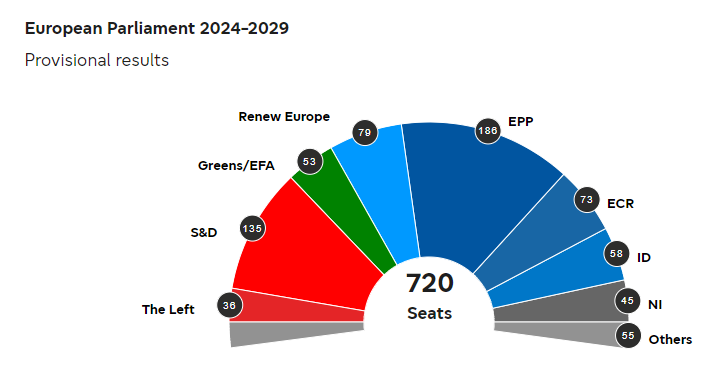

The European Parliament recognises political blocs with at least 23 representatives from a minimum of seven states. This forces small parties to be swallowed up or hover harmless on the fringes. Members of the ruling coalition speak first in debates and that coalition is unchanged after the weekend.

The European People’s Party (EPP) is the largest bloc and led by German Christian Democrats. It’s called centre right and gained a handful of seats. It forms a grand alliance with the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and Renew Europe. The largest component of the centre left comes from the ruling Spanish socialists, while the liberal Renew is dominated by Macron’s Renaissance party.

Across Europe the pattern of parties from right, left and centre is a familiar one. Coalitions are more common on the continent due to proportional representation, party list voting and low thresholds for minority representation. The UK’s first past the post system allows a party to form a government without winning a majority of votes.

Common practice is that the centre left or right allies with the liberals. The latter is the smallest of three but most often in government. It tends to take the economic ministry, which results in stable and capitalist policies in Europe’s core.

Once in a while a grand coalition of all three is required because a protest party does well. Next time things return to normal.

Protests are common in European elections. Turnout was only 51%, although this represents at least a 20 year high. A reasonable number of people felt moved to express their discontent this time around.

The Greens lost a quarter of their seats. Everyone favours the future until asked to pay for it. Facing inflation, high energy costs and surrendering the dominance of the car industry to China, the Green vote fell back to its core.

The initial media message was that the hard right had won. The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) are where the Tories sat before Brexit. Now they are led by the Polish Law and Justice Party and Italian prime minister Meloni’s Brothers of Italy. Both are eurosceptic and in favour of immigration control, which panics most media. Yet Meloni has governed with competence and centrality and is set to take centre stage hosting the G7.

Further right lies Identity and Democracy (ID). Both left and right claim the mantle of democrats, but the right wing version is labelled extremist. Rassemblement National dominates this group following its strong showing and the expulsion of the Alternative for Germany (AfD). The latter’s seats are unattached (NI).

The AfD vote rose 5% points to 16% in Germany while the Greens fell from over 20% to 12%. The domestic opposition centre right came first. AfD operates under a cloud after the domestic intelligence agency labelled it an extremist organisation and the top two candidates were barred from campaigning. Trump supporters may take heart from this performance under pressure.

Outside of Italy the election has the hallmarks of a classic mid-term moan against the local ruling parties. Might it become more?

Spooking the Markets

The three centrist parties controlling the EU Parliament have a comfortable majority. This is despite Macron’s defeat. As such little will change, but a repeat at national level may limit his ability to do much.

Doing nothing does not spook markets. What traders fear is a populist tilt that increases government spending, when France has the third highest ratio of debt to economic size in Europe. This might be called “doing a Truss” after the ill-fated, unfunded spending plans of the UK’s shortest lived prime minister.

This second chart shows that France has been on a bender since the Financial Crisis in 2008. Its government spending shows a similar pattern to the US. Household debt is lower but the big difference is larger company debts, shown in the top section of the chart.

The US has a long tradition of companies raising equity to fund growth. Europe has always favoured debt. Hence an enthusiasm for lower interest rates, which a spending spree in France would jeopardise.

Complacency and Chaos

Why did Macron call an election? Protest votes against immigration and the green agenda work well in European elections. Domestic parliamentary votes are about the economy, national security and competence. The centre held in the EU elections and Macron may expect something similar to dampen the right’s ascendance.

Macron’s coalition has lacked a majority in the National Assembly since 2022. The President has ruled by fiat, passing legislation without a parliamentary vote and this is unpopular. He may therefore, be complacent in thinking the European election results will not transfer to home. Jacques Chirac dissolved the Assembly in 1997 and lost his majority. More recent UK votes on Brexit and May’s election a year later, show miscalculations are common.

Some suggest Macron wants the right to win to prove its incompetence. This would be a remarkable act of altruism given Macron cannot stand for President again. The beneficiaries would most likely be his coalition rivals, as the electorate won’t thank him for introducing chaos.

Chaotic behaviour is why the Tories face a wipe out. The combined polling of Conservative and Reform UK is around 4% points below Labour. This suggests that the right wing vote holds up. Yet as the rivals take lumps from each other, the electoral system will allow Labour to pick up plenty of seats with a minority of the local votes.

The Tory manifesto is about tax cuts, a cap on migration, apprenticeships, more defence spending and hiring doctors, nurses and police. The green policies were dropped a while ago. This angers some while not appeasing the right. Sunak was ridiculed about migrant numbers in a debate. A failure to walk the talk on immigration and do more to control the consequences of green policies, has enabled the rise of Reform.

If electorates have longer memories than flip flopping politicians believe, then Biden’s pivot on migration will do him no good. Immigration and Net Zero are also issues stateside. The similarities with Europe are despite America’s different relationship with migrants.

Immigration’s Lost Lustre

Immigration means different things to different people. To governments it might be skilled workers for the health and IT industries. To urbanites, it may be a cleaner or care worker allowing for a dual income lifestyle. For others it is competition for housing, jobs and healthcare.

The superior economic performance of the US has much to do with immigration. Its population grew 130% since the 1950s compared with 35% in Europe. It also attracts the most talented scientists, academics and entrepreneurs.

Arrivals to America embrace the culture. In New York I lived among Irish, Italian and Russian Americans, proud of both their roots and new nationality. You don’t meet Russian British in London.

There is a sense that this is changing. The positive contribution of immigrants to growth is being questioned. Assimilation is an issue, although nowhere near as great as in Europe. Trump feeds on this and it triggered Biden’s backsliding.

Unemployment is at low levels, stock markets are near highs and wages outpace inflation. But Americans are not satisfied. This chart shows satisfaction is above the lows of the financial crisis and Covid, but well down on pre-pandemic levels.

The chart shows the tremendous bursts of enthusiasm in early Reagan and through the Clinton years. In the UK these were the times of Thatcher and Blair’s Cool Britannia. When reading comparisons between the UK election and 1997, it’s worth noting something bigger was happening in the West.

The 1980s was the release of the individual after a long period of corporatism and industrial strife. The Soviet Union was breaking down and the West was winning. The peace dividend from the end of the Cold War helped unleash the optimism of the ‘90s.

2024 looks nothing like those periods. Wealth is at a high but its distribution is skewed towards a few. Employment is up but there is little job security. Housing, healthcare and education are beyond the reach of many without the state.

So why does the centre hold?

A Quiet Life

My theory is that elections are about punishing people and parties for poor performance. They are a lot less about embracing change. Many voters prefer fewer initiatives, less meddling and to be left alone.

With this understanding, sharp shifts in election results do not signify major changes in philosophy. The right will rise until the centre adjusts to the demands for immigration control and an end to punitive environmental policies. The relative success of the European People’s Party reflects the modest moves required.

Starmer understands a need to be centrist. He knows he must prove himself and victory will owe much to Conservative incompetence. He keeps his powder dry for office.

In the US the voting patterns of most states are fixed. The election will be won in a few swing states. Several are industrial heartlands, suspicious of environmentalism and protective over jobs. This means China tariffs and immigration controls.

These are not protest votes. This is people looking after their interests. National elections are about the low risk option.

Macron gets this. He’s seen the far right win elections before, but never the big ones. He is betting that protests fade when people are asked to vote for their financial future.

The media questions Macron’s motives, while revelling in the uncertainty. Centrism and low risk options don’t sell news.

Traders dislike uncertainty but they do like change. The speed and direction of travel matter more than the level of markets. The more French bonds fall against German, the more they snap back if Macron succeeds. Centrism and low risk do not create money making opportunities.

Meanwhile most voters want a quiet life. They vote for that in greater numbers in national elections. It’s a big reason why they feel distanced from both media and markets.