The Purpose and Prospects of Universities

The culture of questioning authority has served society well. But has it gone too far? It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

A distant cousin graduating university was devastated by her 2:2 degree. She scored zero in three papers that were never taught due to strike action.

My daughter is facing 5-days of strikes at the end of this month and has work languishing unmarked since March. The lecturers’ union is calling off the marking ban, but her first year was paid in full and is best described as incomplete.

With patchy knowledge of the details, we take sides in labour disputes depending on our prevailing views and how directly we are impacted. Many of us harbour preconceptions about the value of universities today. To address these, the first part of this essay examines university finances, on the assumption that who pays the piper calls the tune. One lesson I draw is not to make such assumptions.

If you are happy to take the numbers as read, then scroll past the charts to the second section, where I discuss how academics are contributing to societal upheaval and sowing the seeds of change.

Teaching is worth more than learning

The lecturers’ complaints echo those of many unionised workers taking industrial action. They want pay increases ahead of inflation to make up for having fallen behind in recent years, better working conditions and greater job security in the face of rising contract work.

There are some reasonable requests backed up by misleading claims. Lecturers are not fighting low pay as on average they receive £40,761 per annum, while half the UK population earns less than £27,756. Lecturers are paid more than the £34,109 earned by the average graduate, which suggests teaching is worth more than learning.

The universities are also not awash with cash. The latest numbers show that higher education institutions generate 4% surplus cash, a ratio that has halved in recent years. They do have considerable investments, but these are to maintain grants and pay lecturers’ defined benefit pensions. Gig workers and the private sector don’t get such benefits.

With industrial action set to rumble on into 2024 it’s worth asking why do we have universities and who are they for?

University finances are deliberately obscure

Universities exist to educate students and perform research. In the US, there is third purpose at elite universities in running a sports franchise that is professional in all but name. ESPN estimates that at least $1 billion is bet on the four-month college football season and 8 of the world’s largest 10 sports stadiums are in US college towns. The UK has no equivalent.

Universities UK claim their 142 members employ 815,000 people and contribute £95 billion to the economy, or about 4%. £29bn of that comes from overseas. It seems reasonable that those who pay for universities should benefit from them, but who is that exactly?

University financial data is compiled by the Office for Students (OfS), which receives an annual guidance letter from the Department for Education, setting out priorities and telling it how much to pay. Its latest report is from June 2022, suggesting last year’s accounts are overdue, as the 132 English institutions receiving funding from OfS, or its Northern Irish equivalent, must report by the end of January each year.

At the same time the report was published, the House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts issued its own saying that the OfS had insufficient grip on the challenges of higher education, and that the Department for Education does not hold it properly to account.

The OfS issues accounts under a Transparent Approach to Costing, which means a lengthy series of adjustments to audited accounts. Its final report is only half the size of the document describing the accounting amendments that provide this so-called transparency. Anyway, we’ll go with what we’re given.

Over half of revenue comes from teaching, meaning the payments made by or for students. A quarter comes from research funding and the remaining fifth from commercial operations, investments and donations. The contributions after costs are very different across these operating lines.

Teaching at universities generates a surplus, although this comes entirely from the profit made educating the near 560,000 students from outside the UK and EU. Half of these come from China and India, which is unsurprising given their populations.

Universities’ commercial operations, such as catering, conferences and letting, lose money and research is a financial black hole to the tune of over £4 billion.

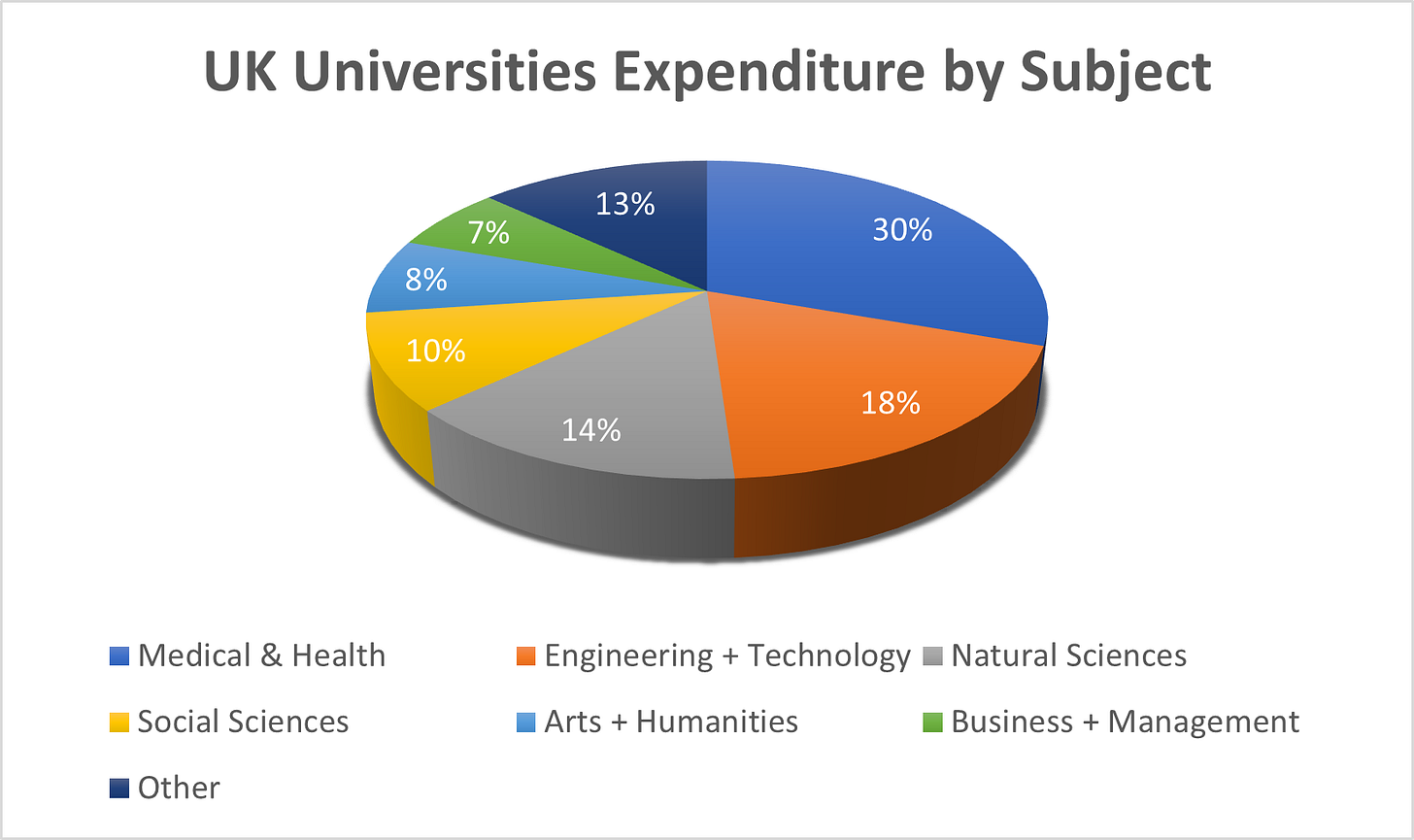

Over half of spending by subject is on health, engineering and natural sciences and only 8% on humanities. Nearly three-quarters of research spending is on the harder sciences.

Given it is research that is putting financial strain on universities, let’s take a closer look at who should be benefitting from it.

Research is a problem of universities’ own making

UK university research has the third highest output globally and receives 10% of all citations. Universities UK claims this is off the back of 20% of total expenditure on research and development, compared to a 29% international average, and with the lowest level of public funding in the OECD. OfS data, however, says 34% of expenditure goes on research.

When we add all the different sources of government funding, the public sector accounts for 60% of research revenue, while charities and industry contribute around a quarter.

Remarkably, the universities manage to lose money on non-government funded projects, as well as on postgraduate students and the research they fund themselves.

To summarise, research loses £4 billion a year, half of which is on university sponsored projects. This is partly funded from government, but mostly by selling degrees to overseas students.

The reasons that university research is failing

As students fund over half of university budgets, are they getting a fair deal? My cousin would say no, but she appears unlucky to be in the 6% of students who have not graduated, or whose finals were partially or unmarked.

More than half of students say their degree is not value for money. This percentage is rising, which is hardly surprising given the Covid-era experience and now the strikes. The recent changes to student loan financing may also have an effect, as the government is expected to write-off around 20p in the pound in future, rather than the 50p from 2012-22.

The DfE claims the average pay of graduates is £38,500 compared to £27,000 for non-graduates. The numbers are suspiciously round, but the gap is similar to other sources. That difference over a 40-year career is £460,000 in today’s money, which might mark the maximum you’d be prepared to pay for the education.

But averages don’t tell personal stories. The debt you take on is certain, but how much you’ll pay back is not and neither is how much you’ll earn.

Another complaint from aspiring students is that they are missing out to overseas undergraduates. These are the main source of universities’ surpluses and it is no wonder they are looking for more. They claim to have no choice.

We have already seen, however, that losses in other areas are the result of choices made by the universities. Closing in-house research projects and cost-plus pricing on company and charity projects would save £3 billion a year. More overseas students are not inevitable.

Academic research in the age of polarisation

University faculty members are qualified to teach and institutions rely on them, which gives them bargaining power and little risk of job losses when on strike. But their qualifications aren’t transferable, making them vulnerable. To change this they must make a name beyond academia.

Not everyone is suited to writing best-sellers, hosting podcasts or starting companies. Getting research published is therefore the most common route to create a name and many institutions insist on it.

What it takes to get research published is changing. This week Patrick Brown published an article about how he had gamed the system to get published in Nature, the once venerated journal of academic learning. There are three rules to getting climate research published.

The first is to support the mainstream narrative. If you identify a number of causes of weather events, wildfires or species extinctions, go with climate change as the reason. If you don’t, your paper risks being rejected by editors claiming your facts are known and because it will not attract media attention.

The second rule is to downplay adaptation and practical solutions. This is the death knell of research, because it exists to provide answers. But Brown claims there is no market in leading journals for hope or opportunity.

The third trick is to abuse the statistics. Never quote the number when you can use the rate of change and pick an obscure metric where the change is high, to garner press attention. This study at Texas A&M University was promoted by highlighting that 3 degrees Celsius of warming will increase temperature-related deaths fivefold, rather than the equally valid point raised that adaptation can significantly reduce such deaths regardless of how much climate changes.

For climate change read race, gender and other culture war issues. In our age of polarisation there is only black and white and you are either with us or against us. Academics seeking publication claim little choice about which side of the line they fall.

The rise of Relativism and the peddling of nonsense

Academics themselves are the reason for this impasse. The culture of questioning led to the belief that there is no absolute knowledge, which is why universities are at the centre of resistance to totalitarian regimes and religions requiring unquestioning devotion. So far, so good.

This thinking has extended to questioning all knowledge. Richard Dawkins argues that as our brains evolved for life on the savannah, there are concepts beyond our comprehension and as a result there are things that are unknowable.

The logical conclusion of this is that any conjecture about the unknown is as valuable as another. This applies in science, social science and the future of climate. It is also used to argue that no culture is superior to any other and that we must therefore respect the outcomes of humanity, however barbaric they seem to us.

The tradition of relativism dates back to the Sophists of the fifth century BCE. Its popularity comes and goes and right now is at a high. This is what students are being taught, what the media is pushing and what therefore finds its way into government policy and all walks of life.

The biggest failing of universities today is that they are peddling nonsense.

The source of all knowledge

Knowledge is created by the conjecture of a new theory that explains the available evidence better than existing theories. There is no certainty because our theories will be improved and technology will reveal new evidence. We know what we know to the best of our ability today.

This is very different to things being unknowable. The unknown has not been discovered yet, but it will be. Humans are unique in our ability to do this.

All knowledge develops from genetic adaptation or human conjecture. We work far faster than nature and hence the acceleration of knowledge since the Enlightenment. Humans have a special place in the universe because of our ability to adapt our environment, as well as adapt to it.

Political, religious and pseudo-scientific beliefs that deny this, which have sacred texts of the Word and experts to interpret it, are backward and must be acknowledged as such by those charged with educating. This is not happening today.

The end of the Age of Experts

Academics are fuelling polarisation by compromising their research to gain attention. They are being pushed to do this by mismanaged universities whose budget issues are largely of their own making. The primary mismanagement is doing unfunded research. Claiming that knowledge is good for knowledge’s sake is ironic in an era when marginal research proclaims the inability to know.

Budget constraints can be alleviated by more overseas students, but that runs into practical problems of housing and infrastructure and political objections about immigration and educating the competition.

The UK could spend more of the public purse on higher education, by upping grants or higher student funding. For this to be political consensus requires more demonstrable value from academia, at a time when we are moving in the opposite direction.

George Friedman argues that the age of experts is coming to an end. Government from the next decade onwards will be by generalists, weighing inputs and creating policy based on what is best for the people. By compromising their research and weakening their credibility, university academics are fostering this change.