The Science and Ethics of Ageing

We can live a lot longer and save money at the same time. Why don't we? It's time to take The Sniff Test.

David Sinclair wants you to be immortal. He’s getting younger and can age and reverse mice at will with genetic modifications. Knock a year from your age every 12 months and you live forever.

Increasing our healthy lifespan by 10 years is worth US$367 trillion according to Nature. That’s enough to adjust to climate change, introduce universal basic income and wipe out the national debt. The annual benefit is worth more than the total US economy.

Healthcare is the biggest expense of government and Western populations are ageing. If Sinclair is right and ageing is a disease that results in cancers, heart failure and the other chronic conditions that kill three-quarters of us, curing it reduces all other fatal illness.

The Science of Ageing

Sinclair is Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School. His book and podcast “Lifespan” explain his theory of ageing and why preventative medicine holds the key to a healthcare revolution. The podcast in particular is full of tips on how to look younger and be healthier for longer.

This is important. While life expectancy rises through time, both The Lancet and The Journal of the American Medical Association show our extended lifespan is spent in frailty and ill-health. Anti-ageing promises a long life that you want to live.

A gene is a segment of DNA with instructions for how to make proteins. Proteins are the building blocks of cells and are important for growth, development and metabolism, the chemical reactions within our cells.

The genome is our complete set of DNA. It’s a blueprint that determines our characteristics and susceptibility to disease. Sinclair accepts around 20% of ageing is genetic and, for now, little can be done about this in humans.

The epigenome is the computer that controls our genome. It uses chemical modifications to DNA and proteins to switch genes on and off. Measuring how often this happens provides our biological age, which is different from how long we have been alive. Our organs age at different rates, with the skin the oldest due to its exposure to the outside world and the brain the youngest and best protected.

When we treat cancers and heart disease we remain susceptible to other chronic conditions. Increasingly, these are in the brain, because by keeping the rest of us alive for long enough we give the brain time to age. This is why Alzheimer’s and dementia are on the rise.

The Finance of Ageing

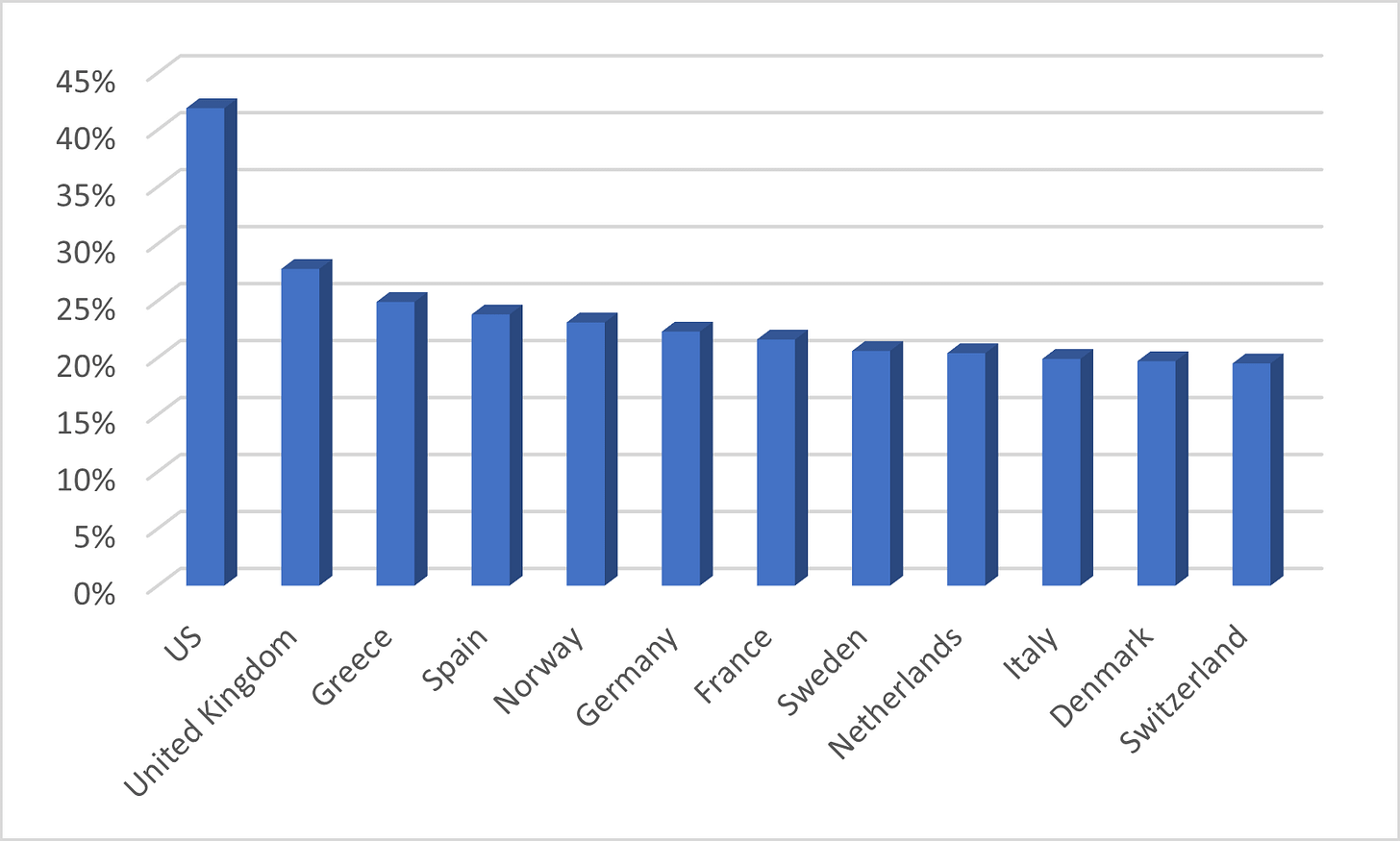

The richer and larger a country and the more private healthcare plays a part, the greater the share of healthcare spending in the economy.

Chronic disease effects 1 in 8 people in the UK and the Kings Fund estimates that the 5% most ill patients account for 40% of NHS spending. Delaying or preventing these conditions would save a lot of money. It would also require a significant shift in how we provide medicine, which focuses on treating symptoms rather than preventing them.

The financial benefits of anti-ageing are not as much as claimed in Nature. This estimated value is based on what staying healthy for longer is worth to people, which includes leisure time. The idea that we might pay more than the value of the total economy to live longer is understandable, but not practical.

This recent article in The Telegraph makes anti-ageing seem elitist, but in truth there are many things everyone can do to slow the passing of time. Most of these are familiar tips for staying healthy, but with the added incentive of living longer.

How to Slow Ageing

Sinclair likens ageing to the build up of scratches on a compact disc or damage to computer software. Eventually the music won’t play and the program doesn’t work. Most of the harm is repairable.

There are three main factors controlling ageing, which are mutually reinforcing.

When we have low levels of amino acids our body gets to work recycling defunct proteins. The accumulation of old proteins is a major cause of disease, including Alzheimer’s. We get most amino acids from red meat and must eat less to trigger this anti-ageing response.

When glucose levels are low we respond by working harder to generate energy. The mitochondria that are key to this are structures in our DNA that generate energy in our cells. We turn on this reaction by eating less sugar.

Sirtuins are a family of proteins fuelled by NAD and are Sinclair’s specialist subject. NAD is a catalyst that increases energy, protects against ageing, improves brain functions, reduces inflammation and boosts the immune system. It is found in every living cell, but levels decline with age, so that by mid-life we have around half what we had in our twenties.

We slow ageing by tricking the body into believing times are hard, which triggers repair and recycling. This may make us smaller and weaker, but Sinclair notes nursing homes are full of little old ladies rather than oversized men. Comfortable, sedentary lives are the enemy and like our ancestors we should aim to be cold, hungry and running some of the time.

The importance of diet

Sinclair’s top tip is to eat less often. This should reduce calorie intake, but it is also critical to have periods when we are hungry. Skip breakfast rather than lunch, because the aim is to go 16 hours a day without eating, as a simple form of fasting. Remember the purpose is to prolong life, not reduce weight, although that is a side effect that would benefit most of us.

Obesity is on the rise. The standard definition is a Body Mass Index over 30 and if you’ve ever had it measured you know it’s not precise. It is, however, a simple way of getting data on a lot of people.

A Mediterranean diet of mostly plants and fish, but including some red wine, reduces mortality. The Asian equivalent is an Okinawan diet that is low in calories and carbs. Okinawans are among the most long-lived and healthy people on the planet.

Exercise and Sleep, Cold and Heat

Aerobic exercise boosts blood flow and brain activity, while training with weights increases bone density as well as toning muscle. Exercise reduces stress and improves sleep quality, both of which lengthen our lives.

Early morning sunlight improves sleep by resetting our natural rhythm. Sleeping regulates these rhythms, but becomes harder as we age, partly because NAD levels determine how well we sleep.

Cold and heat therapy activate our defences and the Lifespan podcast has suggestions on how to minimise the discomfort of these. A sauna followed by the icy plunge pool is one way and the latest infra-red versions may have lasting benefits for skin health as well as anti-ageing.

Supplementation and Drugs

It is easy to become overwhelmed by the amount of supplements we could take. A good diet will provide most of what we need and supplements can top up where ageing slows our production of important elements. Lifespan has a whole episode on this.

B vitamins are important in regulating gene activity and we consume most of these in meat. Vegans in particular should supplement these. We also tend to consume more omega 6 fatty acid than the more useful omega 3. Having followed Sinclair for a while, I take a daily dose of NMN, which converts to NAD. This should be taken in the morning and a spoonful of virgin olive oil aids absorption without a meaningful impact if you are fasting.

Thereafter, drugs such as resveratrol and metformin, familiar to type 2 diabetics, have proven anti-ageing benefits. There is evidence that hormone replacement treatments prescribed for perimenopause have lasting benefits if continued to be taken. All these drugs have side effects and should be monitored by a doctor.

You cannot manage what you don’t measure

We ought to know and avoid food that spikes our blood sugar whether or not we fast and this can be measured without a trip to an expensive clinic. We would improve replacement treatments such as oestrogen and testosterone by knowing our own baselines, rather than relying on averages. As ageing starts from conception, but the government is only going to monitor you when you are at risk, you need to take charge.

Rather like supplements, the things we could measure rapidly get out of control. Sinclair considers these the most important and practical things to monitor.

In theory, your doctor should welcome you producing this wealth of information.

The Ethics of Ageing

The most painful experience of my life was watching my father suffer with dementia and seeing the strain it placed on my mother. We should look after ourselves now we know how, to reduce the burden of care on our families.

Most medicine aims to treat symptoms rather than prevent them. This means we incur costs when people are ill, rather than spending continuously. Politics is not about expense today to save tomorrow and if it were our pensions would be funded.

Knowledge improves with time. My spleen was removed in 1988 as a preventative measure due to a low platelet count and a desire to play rugby. The latest technology suggests this was a monitoring miscalculation rather than a health risk.

Many anti-ageing measures on the market today have similarly unknown effects, and several have flimsy scientific grounding.

Individuals versus Society

We were locked down to prevent the NHS being overwhelmed, despite concerns that the resulting economic hardship would have more severe consequences. Clearly an appeal to the greater good is allowable in matters of health and even liberal European states acted with zeal. Will governments intervene to force us to be healthier?

Probably not, directly. We use taxation to determine how reckless you can be before you make a contribution to the costs of your activity. Smoking, alcohol and diesel are reckless and hence are taxed, while class A drugs are bad enough to ban, albeit ineffectively.

The UK government faces an uphill struggle to ban petrol cars from 2030. Introducing environmental standards, however, and using the private sector to enforce them while pushing the cost onto consumers, results in much grumbling but little resistance.

Bans are generally bad ideas because they rarely work. They also reduce the ability to tax, which is by far the preferred way to regulate our behaviour. We should expect an extension of sugar taxes, more for the revenue they bring than because they are the best way to address obesity.

Discrimination in Healthcare

Most health monitoring is a snapshot and you can fudge the numbers with good behaviour prior to a test. Continuous monitoring generates vast quantities of data that must be stored and processed, which raises questions.

Most likely private companies will collect this data. Who owns it, where will they store it, what can they do with it and should the government have access? You may delete your browsing history, but health records have an important role in advancing science and saving society money. The more the state benefits from data, the greater the infringement of our rights to be left alone.

We already see this. My healthcare provider offers discounts if I go to an approved gym and wear a particular smart watch. I don’t and therefore none of my exercise reduces my insurance costs, even though the provider benefits from my dedication. At some point this may be costly enough to change my behaviour.

Healthcare is already discriminatory, depending on where you live. So is policing, employment and all the things that governments do. If we charged unhealthy people for NHS services, we would be penalising those who have had poorer service for decades, as well as those who choose unhealthy lifestyles.

Plus there is a genetic element to health. Once we restrict services through charging or prioritisation, we are penalising people for their genes. We already punish women for ageing by largely ignoring menopause and we know that race plays a role in predisposition to disease.

The Bottom Line: Poverty Sucks (Again)

Scientific advances hold out the prospect of longer, healthier lives, but raise questions of morality and liberty. Governments do little to help us live longer, but also not much to punish us for choosing not to. The latter will likely change faster than the former.

In the meantime, the benefits of a healthier life accrue to those that can afford them. Publicly funded healthcare exists because wellbeing is a human right and our health is a lottery. It is getting harder to argue this latter point and increasingly difficult to view ill-health as anything other than another burden of being poor.