The Strength and Weakness of Liberal Democracy

Is radical environmentalism a threat to democracy? Are liberal values strong enough to withstand a committed opponent? It's time to take The Sniff Test.

Are you liberal or democratic?

We live in a liberal democracy. The word liberal implies our democracy is not only different but better than other kinds. We brand our democracy as liberal and present it as superior.

Big businesses use the same method to claim everyday items as their own. You don’t have a phone, you have an iPhone and this is not just food, it is M&S Food. We call this marketing and it works brilliantly.

Adding descriptions qualifies and narrows meaning. It implies that there is something wrong with the original and that it can be improved. In politics we call this propaganda. Do you believe in justice or social justice?

Why liberalism survives

Democracy predates liberalism by centuries. Athenians voted on important matters in person, but also practised slavery and denied most of the population a vote. This was not a liberal city and its democratic experiment ended with defeat to Sparta in the Peloponnesian War.

Modern European countries were liberal before they were democratic. The foundations of liberalism were laid shortly after the English Civil War and built upon extensively before universal suffrage. The long wait between talking about something and doing it is a persistent criticism of western liberal thought.

Yet liberalism survived precisely because it was a thought experiment rather than a real one. Nations that tear themselves apart over the rights of individuals might find themselves overrun by powerful neighbours. Liberal thought flourished in Britain given the luxury of geographical separation from its neighbours, while it blossomed in France because that was the hegemonial continental power.

Successful liberal nations set aside individual values in times of trouble. This is either because there is no constitution, as in the UK, or the interpretation of the constitution changes. The political history of the United States is one in which the power of the presidency, with its direct mandate from the people, has grown at the expense of the other branches of government.

The theory of knowledge

The purpose of The Sniff Test is to address common knowledge and question whether it is knowledge at all. It exists to call out the marketing and propaganda that relabels things in order to influence our thinking. The Sniff Test is a pause for thought.

Knowledge is the best available explanation for the evidence on hand. Our understanding improves only when we develop a better explanation. The more robust a theory, the harder it is to alter in the face of new evidence.

Universal theories, such as human rights, withstand the passage of time. Our thinking is inevitably shaped by the times we live in and ours is a technology age that poses new challenges to old thinking. We also face a number of uncompromising political opinions that challenge the outcomes of liberal, capitalist economies. It was ever thus, which is why history is cyclical.

The Leviathan lives

Hobbes’ ‘Leviathan’ was published shortly after the English Civil War. Determined to devise a system that would avoid conflicts, particularly religious ones, exposing the base nature of humans, Hobbes reached an uncomfortable compromise that has proved surprisingly hard to better. His description of the natural order without state control is best remembered for the end of this quote.

“No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Thomas Hobbes - Leviathan, 1651

Hobbes argued that our inherent vulnerability, where even the strongest may be struck down in their sleep, meant that we would willingly hand the state complete control over determining what was a threat and how to deal with it. The risk that we are perceived as the threat is real, but in 17th century England the government had much less reach into people’s lives than in the technology-enabled 21st century.

The phrase ‘state monopoly of violence’ is common in political discourse. Governments control the military, the police, the power to tax and the justice system. When the pandemic came, we were locked in our houses because of the threat of disease. The justification for this, that the first role of government is to protect us, is Hobbesian.

A theory of justice

It is uncomfortable to think that someone has arbitrary power over you. As a result, liberals since Hobbes have searched for something in the state of nature, the pre-political age, that justifies protections such as the rights to life, liberty and property. These can then be enshrined in a constitution, in writing or by precedent, and used to curtail the power of the state.

Rawls’ ‘A Theory of Justice’ is a thought exercise in why we would choose particular universal rights. If we knew about human nature, but did not know where we would be placed in society, what rules would we insist upon before we entered the game. If you did not know whether you would be rich or poor, black or white, male or female, what would you insist upon?

Rawls had a three-part answer. Firstly, we require freedom, as no one wants to find out they are a slave, or be forced to become one because of circumstances. Secondly, we agree to no discrimination, in case we are the injured party. Finally, we seek the highest possible wealth for the poorest in society, because we all have life goals and need the means to achieve them.

This last principle, called the maximin, is the focus of most criticism. Rawls is not describing America, where he lived, but a European social democratic state and there is nothing universal about that model. We all have different attitudes to risk, and Americans are willing to take a greater chance in the lottery of life.

Rawls is also not universal because his system implies, but does not require, rich nations to maximise the minimum prosperity of poor countries. Does liberalism end at the border?

Rawls’ experiment is a consideration of what could be. Other critics of liberalism focus on what should be.

From Marx to Feminism

Marx believed that capitalist societies enshrined liberties that protect the status quo, which is an unnatural state of affairs. A similar argument is used by feminists, which is why many of them are labelled as Marxist. Both strands of thought want to correct the imbalances before the real politics begins.

Marx argued against any compromise with the capitalists, because that was to submit to the system and its description of the natural order. The sole solution is for workers to seize the means of production and use them for the good of the many rather than the few. Violent oppression of workers would be met with violence.

MacKinnon argues that inherent inequality of the sexes should be rebalanced. Hers is a practical, campaigning philosophy, including a stand against pornography, and takes a legalistic approach of removing obstacles one by one. This position is adopted by minorities, and other genders, who insist on recognition in the law. This defies the classical liberal position that we are all equal, because in practice we are not.

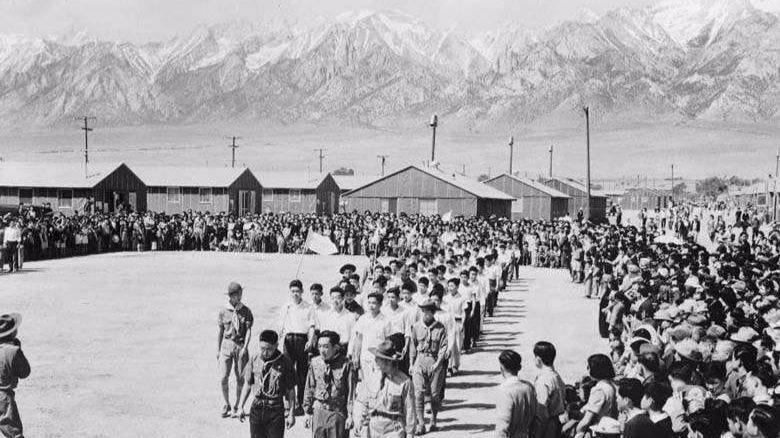

How should we adjust the law? Take the example of reparations for slavery. Money transferred to the descendants of slaves will be spent and find its way back into the pockets of the same people who own everything today. Amazon will welcome government handouts, especially after the boost it received from the pandemic payments.

An alternative is to transfer the ownerships of assets. If slave descendants were given housing in well-to-do areas, with access to the best schools, hospitals and jobs, that would be redress. The fact that it is difficult and arbitrary to determine who must lose their position in these communities to accommodate the new arrivals, is testimony to the likely effectiveness of the solution.

The liberal rights of the potentially disadvantaged prevent this happening. At what point can democracy, the will of the majority, override those rights for the sake of peace and harmony?

What is democracy?

Democracy today is not the will of the majority as it was in Athens, when voters expressed an opinion on all matters. We have representative democracy and it is mathematically impossible to create a perfectly representative system. The essence of democracy is that we can remove bad actors from power.

This is a remarkable thing. The peaceful transition of power is the hallmark and defining quality of democracy. Attempts to copy and qualify it, such as shareholder democracy, are weak imitations that lack bite.

Yet the more liberal our system, the less democratic it is. In the interests of the majority as represented by the government of the day, the UK and US have been remarkably good at overlooking liberty in times of war.

In contrast, it has taken Europe a long time to reach that point, if it even has.

France is 65 years into its Fifth Republic. In previous versions, the president was chosen by elected representatives, but since 1965 it is by popular mandate. This justifies the president taking charge in times of crisis, as in America, and overrides the factionalism that leads to indecision. Hobbes would welcome that the president gets to decide when this is necessary.

Germany and Italy do not have such strong executives. They also use proportional representation, which leads to more parties in parliament and the near impossibility of one-party rule. The consequence of this is an undue influence afforded to the third party as kingmaker, which is why Liberal Democrats in the UK support this system.

Germany has stable governments, while Italy does not. The latter is on its 69th since 1945. A feature of both, however, is the re-emergence of party leaders after every election. The list system, where some seats in parliament are decided on a vote for a party as opposed to a person, allows the elders to return even in the face of crushing electoral defeats. This is neither liberal nor democratic.

The Roots of the Doomsday Crisis

Democracy works because everyone respects the outcome of elections. No rights that pre-exist politics, that stem from the state of nature, are important enough for election results to be overridden. Marxists and feminists may fume at the injustice, but are either too weak or too principled to fight physically for the alternative.

What about environmentalism?

Imagine a radical environmental party committed to no fossil fuels and unwilling to compromise. Democracy must be overridden because the people do not understand the risks they are taking. Such a party need only come third in some European elections to be able to take a permanent seat in government and insist on directing the energy policy of the nation.

For a balanced analysis of what say Just Stop Oil would mean I recommend this piece by Roger Pielke Jr.

What about if that party refused to accept the results of elections. If it took to the streets like modern-day Marxists to do violence to the violence doers. The state of nature, literally, demands that liberal values and democracy stand down in the face of a greater imperative.

The idea of overthrowing societies because of their exploitation is a feature of colonial history. Gandhi insisted on countering violence with peaceful protest, to shine a light on the exploiters and shame them into submission. Others, such as Frantz Fanon, called for violent revolution.

The United Kingdom is a compromise between the desire for nationhood and the collective best interest of the union. Times of peace and prosperity bring stability, while economic downturns reveal deep-seated resentments. The Irish question is unresolved and the perceived injustices date back to Hobbes’ time, if not before. Brexit did not cause this, but it ripped off the flimsy band aid.

In 1920, the Prime Minister reflected on World War I, saying:

"I believe that the war has saved Ireland from civil war. If the war had not come, I believe that there would have been a civil war in Ireland within a year or two."

David Lloyd George, 1920

It’s four generations since Lloyd George spoke these words. Long enough for a Fourth Turning.

I tried, I really tried, to 'get it' about Rawls, but the task always defeated me. He struck me as just being intensely boring. Couldn't understand, and still don't understand, why he was ever taken up by academia.

In my mind I can see Rawls having a quick chat over coffee with his publisher. And the publisher, eyes suddenly brightening: 'John, do you think you could make a crashing 500 page book out of that?'

And so was born a world of very mild, but unduly prolonged, student suffering.