What’s the big deal with debt

As long as governments have borrowed people have predicted collapse. Will it ever happen? It's time to take The Sniff Test.

From Socrates to Orwell

Rising government debt has been a problem for so long that it has ceased to be an issue for politicians on either the left or the right. Does it even matter?

One of the joys of newsletter writing is the feedback. Often this is incidental to a conversation you’re having about a different topic and someone notes how they enjoy reading the articles. Occasionally there is a critique that shakes the foundations.

It is the job of the philosopher to make you think. Socrates was supposedly put to death because his interminable questions, which were designed to have others figure things out for themselves, exasperated people who wanted answers. We see the reverse of this in business when someone says “Sort it out will you” and an analysis of the root cause of the problem is never undertaken.

The job of the essayist is to have an opinion. The great essays often divide into two parts with the first being an explanation of how things work and the second a prediction of what happens next. If the analysis of the subject is sufficiently insightful, then the essay is remembered long after its forecasts are proved hopelessly wrong.

An example is Orwell’s “The Lion and the Unicorn” written at the darkest moment for empire in February 1941, when Britain stood alone against fascism, the Soviets had yet to break with Hitler and the US was still an onlooker. Orwell’s description of what it is to be English makes this essay relevant today, even though his prediction of post war reconstruction by a socialist state that would do away with both the House of Lords and the public school system was wishful thinking. In seeking to ice the cake of an argument the essayist overreaches.

A second instance is David Hume’s “Of public credit” published in the mid 18th century. His surgical dissection of the consequences of government spending gives way to the expectation that Britain must default on its war debts. The 250 plus years that followed have thrown up many pale imitations and there is always someone railing against government spending.

Will they ever be right?

The Significance of Healthcare

Hume wrote at a time when the primary government outlay was on the military and there was no income tax. He despaired of pointless European wars that drained the exchequer while identifying three ways for this spending to be funded.

The first was by conquest, which was a prescient observation. Hume died before the public debt ballooned far more than he could imagine to pay for the Napoleonic Wars, but Britain’s victory delivered an empire. The ensuing riches turned deficit to surplus and made the pound the world’s sovereign currency.

The second way to fund spending is taxation. The public’s ability to pay increased as a result of the jobs created by the industrial revolution and subsequent economic development, but as today’s debts exceed the size of the annual economy, tax is no longer the answer. In the chart the UK is orange, the US brighter green and Japan in yellow.

The final means of funding is issuing debt. Hume considered this by far the easiest and hence the most common course of action and he foresaw debt levels continuing to rise. The critical observation in his essay and why it still resonates is that the ease with which debt may be issued leads to lazy political decisions. For Hume this meant military meddling in European political affairs, while a modern equivalent may be promises of spending on health and welfare.

Of those two health is the issue. The US Congressional Budget Office forecasts the path of debt for the next 30 years. As it is not possible to predict future changes in laws or when recessions occur, the analysts don’t, and this leads to a smooth forecast line that we must accept is different to the choppy reality. The highlight of these forecasts is that while social security and discretionary spending level out, rising government debt relative to the size of the economy is caused by healthcare spending and interest payments.

Higher healthcare costs are a result of an ageing population, which is a drawn out affair, mitigated by immigration and the promise of healthier lifespans. What the charts tell us is that at some stage politicians will have to grasp the nettle and curtail healthcare spending. To understand the difficulty of this imagine going to the polls in Britain today announcing you will cut the NHS.

The charts also tell us and the politicians that there is no immediate problem. Election cycles are short, political careers can be as well, and kicking the can down the road is the smart option. And this is the primary critique of “the debt crisis” thesis – it’s not a crisis at all but a background issue that could be triggered by a real crisis, such as a war.

One complication of modelling economies, stock markets or political cycles is false positives. These occur when the conditions you expect to trigger an event do not, because things change. Economic models are littered with caeteris paribus assumptions, meaning other things equal. Other things are never equal.

This next chart shows interest costs as a share of tax take in red and long-term interest rates in blue. The tax cutting, defence spending Reagan years of the 1980s and the recession of the early 1990s, coupled with the new costs of warfare in the Gulf, contrived to push interest payments to over 15% of tax revenue. Congress enacted a bipartisan plan and Clinton’s presidency featured a few years of government surplus.

As interest payments as a share of tax take approach similar levels to the early 1990s there is despair over polarised politicians failing to act.

What happens if nothing happens this time around?

The primary effect of policy is on the stock market

The prevailing economic orthodoxy is that supply and demand for money and labour determine the level of inflation, employment and thus national income. The Federal Reserve has the task of managing both inflation and unemployment although its tools to do so are confined to the monetary system. Other central banks have stricter mandates to control inflation, usually by targeting an arbitrary level that is assumed both benign and acceptable.

As a consequence there is great spectacle around the decisions made at central bank meetings and incredible amounts wagered on whether policy continues as before or pivots. George Soros calls this reflexivity as an explanation for where theory and practice meet. Even if monetary policy has little or no impact on the economy in the way the theory assumes, the consequence of the volume of bets around the policy has its own effect that spills over firstly to markets and potentially to the wider economy.

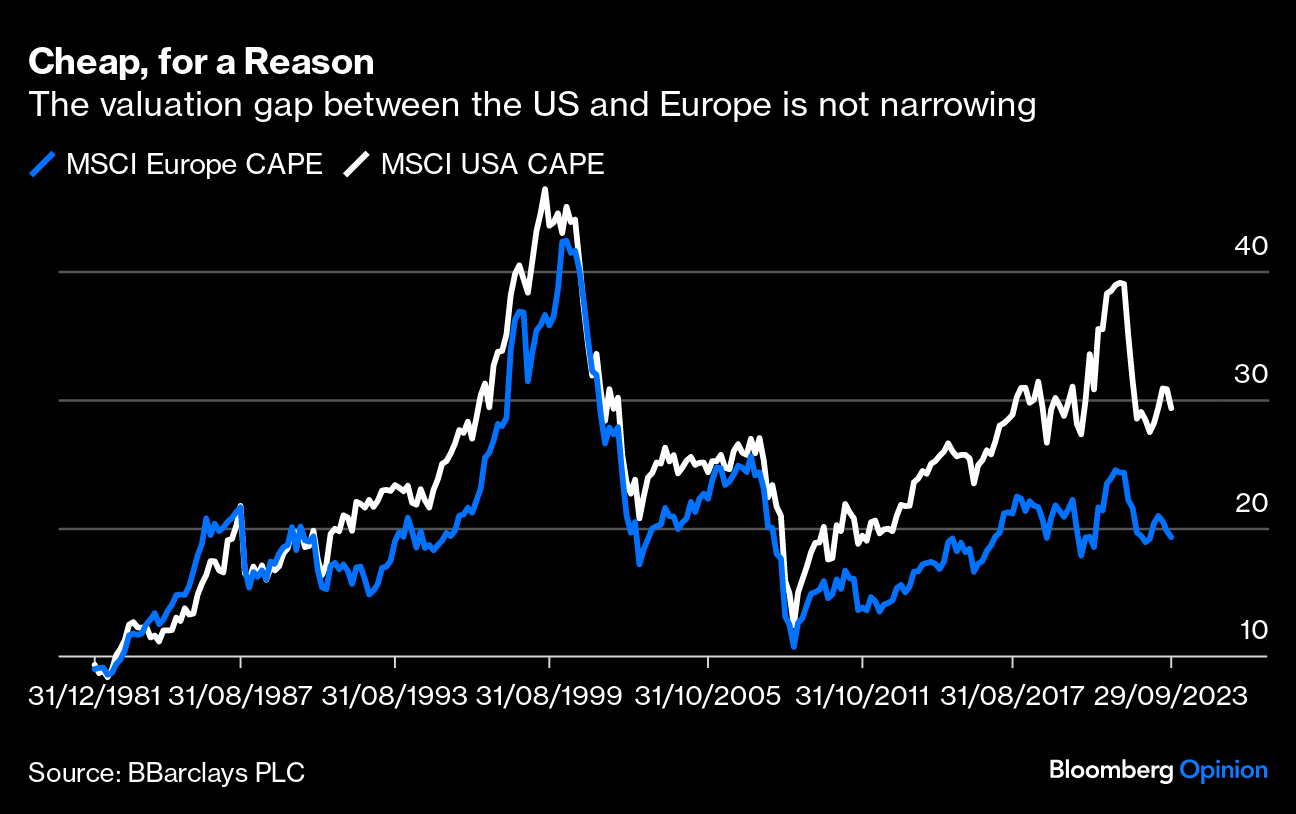

What then is the consequence of the unprecedented credit creation since the Great Financial Crisis 15 years ago. Last week I showed a chart of the US stock market thrashing the rest of the world since 2007, while noting that neither faster economic growth nor better company profits could fully explain this performance. This chart captures both ideas using something called the cyclically adjusted price earnings (CAPE) ratio, which is a fancy phrase for the historic average valuation of the market.

The US market is in white and Europe in blue.

The chart shows that the US stock market is progressively more expensive than the rest of the world. A common justification for this is that the US dominates the technology industry which has better long-term prospects than, for example, the mining and banking stocks that are heavy components of the UK stock market.

The concept of CAPE, a 10-year moving average, was Robert Shiller’s and he shared the 2013 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his work on the empirical analysis of asset prices. Like the great essays, the theory can be split into two parts. The first is the analysis describing what has happened. The second is the prediction that stock market valuations fluctuate around an average level.

Take another look at the chart above. What is the average level around which the white and blue lines fluctuate? Waiting for things to normalise takes about as long as waiting for demographic changes to impact economic growth. Much as politicians kick the debt can down the road, most investors ignore this theory because it has no relevance to quarterly, annual or even longer term performance.

As well as not being much use day-to-day, the theory has another problem explaining why the US has gotten more expensive than Europe since 2007. Other things are not equal. The reason is the expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and the unique position of the new dollars created at the heart of the global financial system.

The main consequence of US monetary policy since the financial crisis is to make US financial assets more expensive than those of the rest of the world and Americans relatively richer as a result.

That wealth enables the US to remain preeminent. When the enemies of the US seek the root cause of US power, they alight on the central role of the dollar. This is what must be undone.

An alternative view of how the world works

Prevailing orthodoxy may be wrong. Different explanations of how the economy works reach different conclusions. Here’s another explanation which I’ll greatly simplify.

When one company spends money or invests then its resources are reduced. But the resources of another company are increased. What holds at the individual level does not apply to the broader economy. Every debt is matched by an asset, every credit has a debit and everything always balances.

When companies invest they generate profits, initially for other companies and then for themselves. These profits in aggregate equal all the spending and saving decisions of the rest of the economy. When governments raise debt and spend, the money finds its way into corporate profits. There is no imbalance about to topple over.

Eventually company enthusiasm for investment leads to too much production and there is a price collapse and recession. The weakest go bust, new firms are formed, while the majority of companies start the cycle over again. The level of interest rates doesn’t matter. This is why left-leaning economic theories and politicians focus on the “real economy” and largely ignore financial markets where the consequences of monetary policy play out.

There’s no Catalyst for War

To defeat an empire you must strip it of its prime assets. Michael Taylor (

) points out that Rome was financially stretched for hundreds of years but fell only when it lost its grain supply from Africa and then its resources in the near east. The Napoleonic wars did not bust Britain, but the loss of empire after the second world war blindsided Orwell and eventually led to the debilitating devaluations of the pound in the 1960s. The equivalent issue for the US may be its dominance of technology, which is why the Taiwanese semiconductor industry is such a great prize and the battle over clean tech likely to be bitter and prolonged.What you can’t do is outspend a Great Power. The investment in the war machine sustains its economy until you lose and it captures your assets. Where once this meant occupation, today all that is required is ownership through investment.

The disturbing instances of warfare in Ukraine and Gaza, sabre rattling in Serbia, Turkish encroachments in the Caucuses and Japan’s reawakening in Asia, do not seem to have common cause. These events are consequences of deep-seated animosities that rise up periodically and now is unfortunately such a time.

The good news is that the US and China are talking. President Xi will visit the US for the first time since 2017 for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in San Francisco this month. While there he will meet Biden and may extend his visit with technology company leaders. The global confrontation that could cause debt levels to spike and trigger a financial crisis is not about to happen.

The upshot is that debt doesn’t matter till it does and now is not that time. Congress may yet rein in spending at some time before the end of the decade and the culture wars that divide us may dissipate. The fly in the ointment of optimism is that this most likely requires the voting population to agree to reduced spending on health. At the risk of being more philosopher than essayist, I’ll end with the question of whether that could be the epicentral issue of our time.