Deposits - big banks don’t need them and small banks can’t afford them. But the real question is how did we get here and whose interest does it serve. The trickle down from bank bailouts is supposed to benefit us all. It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

A former boss of one of the world’s largest banks once told me that the ideal interest rates were between 5% and 7%, moving a little and often. Much above 7% and people struggled to pay back loans, while below 5% meant bank profits suffered. The little and frequent movements allowed a brief widening of the gap between loan and deposit rates, squeezing a bit more out of customers every time.

Interest rates have not been 5% in Europe for years. They only recently returned there in the US and markets are betting they fall sharply. Despite the fastest rate rises on record, most savings payments remain paltry. Why?

The Bank of Dave

“Bank of Dave” is a feelgood movie and a streaming hit in the UK this year. It is about the struggles of a self-made man setting up a bank for local people in a northern English town. It’s based on a true story.

It won’t spoil the film to know that the real life Dave is still waiting for a banking licence. Modern banks are supposed to big, safe and based in London. To keep things this way, you are required to raise a lot of capital to be a bank and, if you cannot, you must be an independent lending company instead.

Local banks are at risk of local problems, such as factories shutting, and lack the spread of business to survive downturns. New banks are untested and asked to take less risk than established ones, making it hard to get started. Hence, according to the real Dave, he is not allowed to use the word deposit.

The regulators have a point. The only way to outgrow local problems is to grow, and much faster than other banks. This means adding a lot of risk in a short time, which rarely ends well.

Northern Rock grew mortgages rapidly and eventually ran out of funding. HBoS did something similar at a larger scale and ended up as part of Lloyds Bank. Every crisis leaves us with fewer banks.

Get Out of Town

If there are two sweet shops in your town and one goes bust, many of its customers will move to the other shop. It can be good news when your competition goes out of business. Even if total demand has reduced, your share of what’s left is greatly increased.

This is not the case with banks. When one gets into trouble, people withdraw money from others. If there were two banks and one went bust, you’d probably move your money out of town.

One role of regulators is to make banks more like other industries. The ideal outcome when one is in trouble is an orderly transfer of its business to another. The new owner does not want any high risk loans, so the government keeps them.

Insurance and Moral Hazard

One way to reassure savers is to provide deposit insurance. If the bank gets into trouble, then you get your money back, provided it’s no more than $250,000 in the US and £85,000 in the UK. The schemes are paid for by raising money from healthy banks.

While few individuals deposit more than the insurance limit, many businesses do. It’s convenient to keep your finances in one place, and banks offer incentives for giving them all your business. When Silicon Valley Bank got into trouble earlier this year, it turned out that a lot of start-up technology companies kept all their money there.

In order to avoid wiping out California’s technology industry and its venture capital backers, the US authorities guaranteed the lot. When SVB’s larger neighbour felt the shockwaves, the authorities quickly handed the keys to JP Morgan. In so doing, they overlooked a law designed to keep things competitive, which prevents a bank holding more than 10% of deposits in the country.

This may not matter yet, because compared with the UK, the US looks overbanked. There is a credit institution for every 190,000 people in the UK. This is two and half times fewer than in the US.

People worry that deposit insurance causes ‘moral hazard’. This is when you behave differently knowing that someone else is picking up the bill. Let a teenager have your credit card for a night if you want to know how it works.

In reality, deposit insurance is a means of avoiding panic. Bad banks still disappear and good banks cherry pick the best bits of business. Over time, there are fewer banks and less competition.

Big Banks Don’t Need Your Savings

The larger the bank, the more options it has. As more people approach retirement, pension funds seek steady, safe returns and the debts of large banks are second only to governments in meeting this demand. Big banks can borrow lots of money and deciding what to pay for your savings depends on how much the alternative costs.

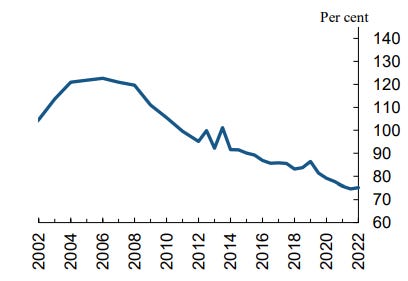

There is a simple ratio of the amount of loans to the value of deposits that has been used to measure risk for decades. Here it is for banks in the UK. The lower the number, the more deposits there are for each loan and the less the bank needs your money.

Note how this century’s peak in loans to deposits was just before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 15 years ago. Banks had been stretching themselves to grow rapidly, especially in mortgage and property loans as was the case for Northern Rock and HBoS. As a result, loan to deposit ratios are now capped at 105% in the UK and 100% in the US, but the big banks aren’t even close.

In the US, there are even fewer loans per deposit, especially after the government handed pandemic payments to pretty much everyone. This money either went directly to the banks, or ended up deposited there once it was spent.

The bottom line is that you can take your savings out of a big bank and it won’t care. In the UK, where only big banks have branch networks to capture our deposits, this is a reason why savers have suffered for years. But it wouldn’t be The Sniff Test if this was the full story.

Extraordinary Behaviour

The US was not the only country to make pandemic payments. The UK funded its version with new debt at low interest rates to a special company funded by the Bank of England. Knowing exactly what was coming, the Bank asked the government to cover any losses that might occur.

As my former colleague

points out, these losses are already £200 billion, for which taxpayers are on the line. This is before servicing the debt and long before paying it back. The cost comes from issuing debt at low interest rates and watching its value collapse when they rise.The Bank of England sets interest rates and was well aware that they would be rising to curb inflation. The next move in rates is bound to be up when they are at zero. This makes other behaviour at the Bank of England harder to explain.

The Bank runs the Prudential Regulatory Authority. This body monitors the largest banks, insurers and asset managers and ensures they do not imperil the health of the economy. There is nothing going on in the UK’s largest financial institutions that the Bank does not know about.

In September of last year, the Bank of England pumped £65 billion into financial markets to stop your pension savings evaporating. All the focus was on the Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget given the thumbs down by traders, but the Bank knew this would happen. Despite responsibility for financial stability, it watched on while pension funds took huge bets that interest rates would stay low forever.

Hong Kong Calling

In August 1998, I was awakened in London by an early morning phone call from Hong Kong. The authorities there had announced they were buying 10% of the stock market and, as this was the end of capitalism, share prices were in freefall. I was due to spend the day explaining why to invest in Hong Kong, and the kindly caller figured I might need an early rise to collect my thoughts.

Disappointingly for some, this event was not the end of capitalism. The price of anything, shares included, is a function of scarcity. Inflation, which is the price of goods and services, has shot up due to the reduced supply of those goods and services, most notable on empty supermarket shelves. With similarly reduced supply, Hong Kong shares quickly bottomed at a level they have not fallen back to since.

Although far from the first manipulation of markets, the success of the Hong Kong intervention did not go unnoticed. In last week’s post, I talked about authorities supercharging the dotcom boom by injecting money to counter the supposed Y2k superbug. The subsequent clawing back of the money helped trigger the dotcom collapse.

Jump Starting Growth

There are three ways that an economy grows. Population rises to provide more workers and customers, the productivity of those workers rises due to new technology and investment, or we borrow money and spend it. Ideally, borrowing is spent on new technology and investment, but if your political career is on the line, anywhere will do.

The growth of central banks is a worldwide phenomenon. The trend has been upwards since the Global Financial Crisis, but really kicked off in response to Covid. Central banks such as the Federal Reserve and Bank of England are seven times larger than 20 years ago.

Central banks create money when necessary. During the GFC, the system needed saving and the authorities bought safe assets from investors. In turn, they bought more risky ones, meaning stock markets recovered. There was waffle about the benefits trickling down to ordinary folk. During Covid, the ordinary folk were at risk and they got the money.

The trickle down economy is the theory behind tax breaks for the wealthy. This means lower rates and tax savings for private investments. You must already be wealthy to make these because of rules restricting access. UK pension funds invest only one pound in 25 in fast-growing private markets.

Back in 2008, lots of people gnashed teeth at the inevitable inflation that money creation would mean. We did get inflation, but only in the price of investments and not in goods and services. The first part of the plan worked and investors took more risk, but the trickle down to ordinary people did not and they were angry.

Banks were bailed out banks 15 years ago to protect our deposits, preserve our jobs by keeping the economy moving, and cover for the inevitable losses on property investments. As with Covid payments, the government issued more debt and the Bank of England, the Fed and the ECB ensured someone bought it. Now, if we don’t have the money to make the interest payments on the debt, the Bank creates more.

Is that good or bad for banks?

Given public disquiet about the handouts, the authorities required banks to hold much more money to back every loan. Even new banks like the Bank of Dave. The banks make fewer loans as a result and don’t need your deposits to fund them. Hence your savings rate sucks.

The loans banks do make don’t help much. To encourage people to borrow, interest rates fell to zero, well below the 5% at which the big boss told me that banks would be hurting. Even then, loans are made to people with collateral, i.e. existing wealth, because these are less risky for the bank.

In making banks hold more money for every loan, the authorities prevented the trickle down economy working. In pushing interest rates to zero, they made money free. Bosses at big companies borrowed to buy shares, either in competitors or their own businesses. The latter is attractive when you pay yourself large sums in those shares.

Giving the money straight to the people would cut out banks. Digital currency could be sent to our smart phones. That’s a problem.

When the trickle down economy does not work, people get angry slowly. Covid showed that paying them directly results in rampant inflation. People get angry quickly. The authorities cannot risk giving people money because they buy food and iPhones rather than company shares.

How do ordinary folk play the game with the weak hand we’re dealt.

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em

Remember, bailouts are to kickstart growth, which requires more risk to be taken. This includes buying shares on the stock market. People might be forced to do this.

In the last week, the Bank of England’s Governor took the unusual step of calling on UK pension funds to increase risk taking. The think tank New Financial estimates that if pension funds go back to how they were invested ten years ago, then £360 billion will flow into UK shares.

If you have a defined benefit pension and work in the private sector it is probably closed to new investment. Nine out of ten schemes in the UK are. You will still receive your pension as promised and it’s best to sit tight.

If you have a defined contribution pension, meaning there are no promises as to what your retirement income will be, you should check the risk profile. The younger you are, the more time you have to accumulate gains, including riding out the inevitable market dips. Young investors can take more risk, meaning investing in equities and checking out the alternative investments offered by their pension providers.

The closer you are to retirement, the less volatile the investments you should own, which means bonds. The Bank of England showed that bond funds are not safe investments when mismanaged, and then showed they are by bailing them out. No one wants an angry generation of pensioners left empty-handed.

If you just want to earn higher interest on bank deposits then you will need to shop around. Banks offer teaser rates on savings accounts, but these run out and often return to low levels in the hope that people don’t notice. Some businesses offer very high rates of interest, but they may not be banks, or they may be based outside of your country, which means you won’t have deposit insurance.

In the UK, basic rate tax payers receive £1,000 tax free and less than one in 20 people earn more interest than that. The allowance for higher rate tax payers is £500. If you earn more than that in interest then you can move to the next level of tax protection.

Cash Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs) are a way of increasing returns. You may invest up to £20,000 a year tax free, but this allowance is for all your ISAs, so works best when cash is your only scheme and you already receive the tax free amount of bank interest. Look for a flexible ISA, which means you may move money in and out without fees or penalties.

You can deposit with the government directly by using National Savings and Investments (NS&I). This has competitive savings rates on accounts and offers ISAs. If you are prepared to lock money away for a year, you can earn over 4%, but you could do that with your bank as well.

NS&I used to offer savings certificates for one or more years, with interest rates linked to inflation. This was a good way for the government to collect cheap money when inflation was low, but when it picked up they stopped. Your existing certificates can be extended and are an attractive option while UK inflation remains high.

Sweep accounts automatically move money from low interest current or checking accounts to higher interest savings accounts, and back again when you need cash. They are available for business accounts in the UK, for a fee. Brokerages may offer these accounts, but check whether the firm is covered by deposit insurance before putting your savings there.

When I asked my bank about sweep accounts for individuals, it told me I had to do this by logging on every day, checking my balance and moving money myself. The issue in the UK is that we love our free banking and won’t pay fees. As a result, banks offer lower interest rates and fewer services compared to banking in countries where fees are normal.

With big banks holding more deposits than they need, large demand from pension funds for bank debts that stand in for deposits, and low loan growth due to a sluggish economy, your savings rate may disappoint for years. This is partly a result of rescuing the banks back in 2008-9 and a lot to do with the continued increase in government debt ever since. It’s getting harder to see how this benefits ordinary savers and citizens.