Why The West Still Supports Israel

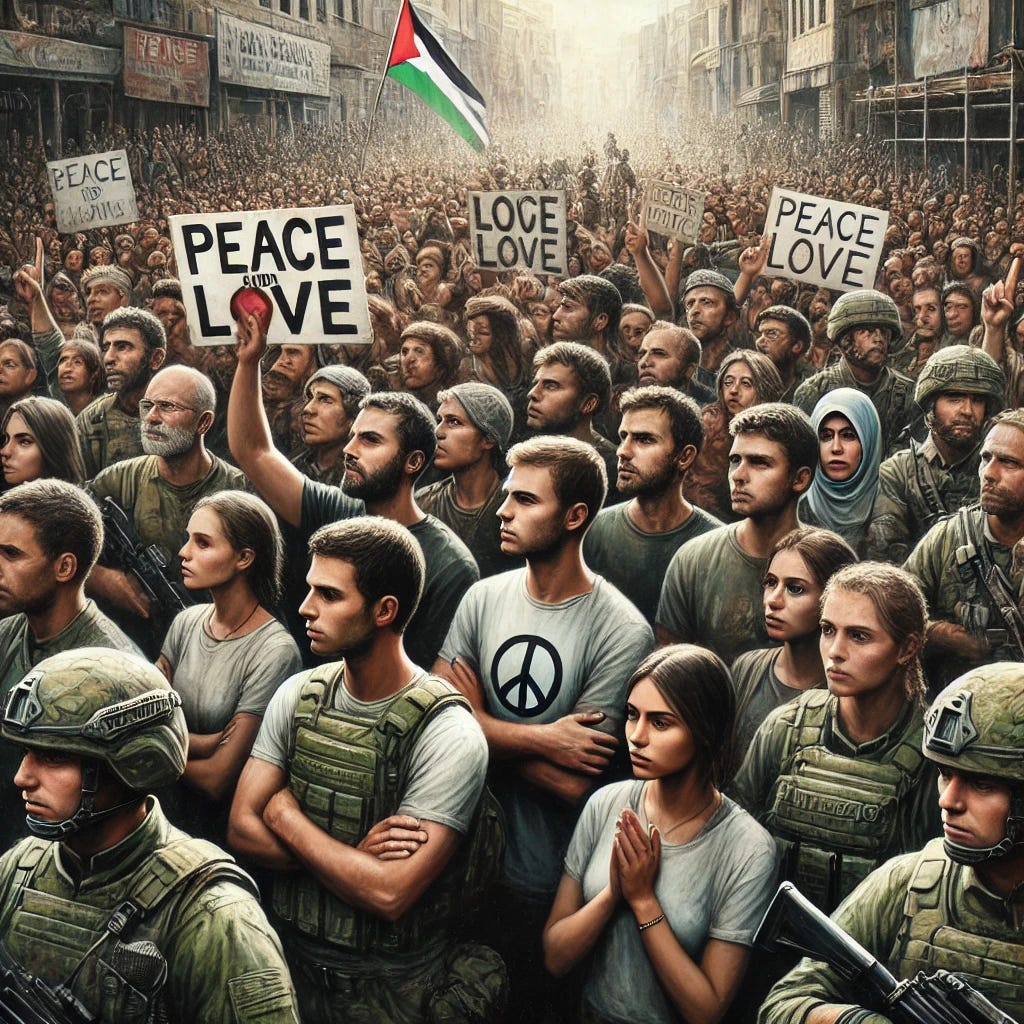

Both peace protesters and politicians ultimately align with one of the Great Powers. It's time to take The Sniff Test.

Sinister Slogans

During his days as an environmental campaigner, my brother marched round the house declaring that if you weren’t part of the solution you were part of the problem. This sinister slogan is used by generations of activists to justify a war on the passive middle classes. The goal is to get them into the streets in sufficient numbers that the authorities start to listen.

The success of this strategy depends on keeping your radical elements quiet. While millions are appalled by the death toll in Gaza, far fewer want to stand alongside masked radicals chanting “From the river to the sea”. If you stand too far outside the Overton Window then you lose the argument.

It is a recurring theme of The Sniff Test that opposition politics is far easier than governing. Opposition makes it easy to paint issues as black and white, while ignoring the dilemmas that turn leaders’ hair grey. Few issues are straightforward right versus wrong and even those that are require sacrifices to resolve. Opposition is about overturning policies and ejecting leaders, it’s not about resolving issues.

An emerging theme of this newsletter is the absence of universal rights. Rights evolve as the principles accepted by societies at particular points in time. So what exactly is the principle that justifies turning a blind eye to Israel’s atrocities in Gaza?

Action and Inaction

The Arab claim to Palestine relies on a long history of being the largest population in the region. The belief is that the majority should form a government free from outside influence. While this sounds democratic, it has never been the basis for United Nations resolutions or negotiations between Jews and Palestinians. Ignoring the ability of outsiders to shape the region has a heavy cost and leaves a lingering resentment of the great powers.

For six centuries after the Crusades, Palestine was governed by Muslim rulers, the final four as part of the Ottoman Empire. In their declining days, the Ottomans sold land in an attempt to bind colonial populations to their fading glory. International Jewish interests began financing land ownership in Palestine. This accelerated after World War I, during 25 years of UN-sanctioned British administration.

British interest in the Middle East was a longstanding policy to protect the passage to India. Nelson was disfigured while victorious at the Battle of the Nile, which stranded Napoleon in Egypt and won Britain control of the Mediterranean. At the time, Europe’s emerging industrial might was built on coal, which was threatened from the mid-nineteenth century by the emergence of oil. Thereafter, the Middle East gained additional resonance. Palestine has always been part of a bigger strategy.

British interest conflicted with Germany, which also sought oil. The Germans allied with the Ottomans and had the upper hand, until American financing swung the Great War against them. The repeated lesson of history is that if you want your rights respected, you need to align with the victorious great power. Israel does this effectively.

Britain and France spent a lot of World War I deciding how to carve up the Middle East assuming an Ottoman defeat. Italy was afforded a sliver of land but was unable to resist the emergent Turkish nation’s claim to it, while Russia’s share was forgotten once the Bolsheviks seized power. Britain committed to both a Jewish state and Arab self determination in this period, but it was the Jews who took action.

Both Jews and Arabs knew that once the British mandate ended, control of Palestine would depend on population numbers and land ownership. The Arabs had the population advantage despite an influx of Jews escaping Eastern Europe, but were divided by infighting. Meanwhile, Jewish settlers accumulated land, often from impoverished Arab farmers. The theme of a large but disorganised Arab population, pitted against a well-funded and disciplined Jewish minority, is a consistent theme in the Middle East.

Israel declared independence the day the British mandate ended in May 1948. The years either side featured the first three in a series of conflicts lasting into the 1970s, in which Israel overcame Arab forces. UN Resolution 181 issued in 1948, proposed the two state solution in Palestine that remains the policy today. The Palestinian Arabs refused to accept this, insisting on the right of the majority to rule. Israel responded with cajoled and forced emigration of Muslims, most often into neighbouring Jordan. Israel’s population today comprises over 7 million Jews, around 2 million Muslims and a smattering of others.

Since its early days, Israel has occupied more land than afforded it under Resolution 181. It seized control of Gaza and the West Bank after the 6-Day War in 1967. The historian Niall Ferguson argues1 that America has been the hegemonic power in the region since the Yom Kippur War in 1973. Cambridge professor Helen Thompson believes the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 allowed the US unalloyed access to the region. Either way, Israel’s small population survives under American technological and military protection.

In 1988, the Palestine Liberation Organisation in exile adopted the two state solution under Resolution 181, arguably 40 years too late. A new force quickly emerged to oppose Israel’s existence. It inherited the slogan from the river to the sea, which is heard at demonstrations in European capitals and on US campuses. It’s called Hamas.

The Pyramid of Conflicts

This potted history serves to show that Israel does not exist due to existential guilt over the Holocaust, or the numerous pogroms and persecutions of Jews over the centuries. Neither does it reflect a US in thrall to Jewish financiers. Ferguson argues that the US has no particular interest in Israel’s survival, but must be seen as a reliable ally worldwide. This is in contrast to Russia, whose influence will suffer as a result of being unable to maintain Assad in power in Syria.

Ferguson expects a new power balance in the Middle East. Historic precedents such as the European wars of religion, are little guide to what comes next, because Europe was shaped by nation states. In contrast, the Middle Eastern conflict is between the hegemonic US and substate actors sponsored by Iran. This is war by proxy and Israel is a proxy for America. Its ability to overplay its hand in Gaza is because of the reality, however uncomfortable, that creating a Palestinian state today would be a win for Iran and Russia. The result would be a flood of refugees returning to rebalance the populations and renewed calls for Arab self determination.

International conflicts may be seen as a pyramid. At the top is the battle between the US, Russia and China. This struggle is global, technological and economic. The fighting is done by proxies in regions around the world. The conflict is riven with inconsistencies, not least the vast trade between the US and China. Nonetheless, it is an existential battle that no one dare lose.

In the second layer of the pyramid are hot wars where the great powers are once removed. Ukraine, Syria and Israel are standout examples. Below this are regional conflicts with tactical significance, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s support of anti-Houthi factions in Yemen. At the bottom are distant conflicts, including France’s accelerating ejection from its former African colonies.

In each level of the pyramid, the combatants can be coloured according to their alignment with the US, Russia or China. Russia is seen by some as a vassal of China, doing the military work, while China concentrates on technology and economy. Their relationship, however, is fluid and opportunistic. Russia exercises geopolitical power through its reserves of fossil fuels, on which both Europe and Asia rely.

Smaller countries are the foot soldiers in a larger conflict. Israel fights Iran and Russia by battling Hamas and Hezbollah, while the Syrian Kurds do likewise by fighting the splinters of the Islamic State. The US must protect them both. Saudi Arabia plays the role of regional conciliator. Since the Revolution of 1979, Iran has lead the opposition to the US presence in the Middle East. Turkey wants more influence but until recently lacked power. It vies with Iran for leadership of the Muslim world and the US indulges its regional priorities, because ultimately this competition aligns Turkey against Russia.

The Palestinians are aggrieved at their exclusion from power. America is blamed for being the leading authority in the region. Peace protesters outraged by war, ignore the pyramid of conflicts that dictates every country’s behaviour.

The Impact on Rights

Today’s environmental campaigners are losing the fight against fossil fuels because of the high cost of energy in Europe. In desperation their stunts become more radical and less appealing to the middle classes. Palestinian supporters must learn this lesson.

The Palestinians have the sympathies of a majority in the West, but will only win through a long campaign similar to the one that changed South Africa. The Middle East is of greater significance and the domestic political pressure required to alter longstanding diplomatic and military ties will take time to build.

The US indulges Israel in defiance of the United Nations, because to do otherwise would diminish its influence with its remaining allies. Maintaining a web of proxies and supportive nations is essential to winning the great game atop the pyramid of conflict. In the fallout, we see how little human rights matter in some societies.

Jay Mens and Niall Ferguson. “’The New Europe?’: European Diplomatic History and the Future of the Middle East.” Hoover Institution, Caravan Notebook. Hoover Institution Press, December 2024.