How to be Confident

Does advice to think positively work? How to use AI to write a self-help bestseller. It’s time to take The Sniff Test.

Are you a confident person? Would you seek help to increase confidence?

Around 15,000 self help books are published in the US each year. Books about confidence have the highest demand, at around 10% according to WordsRated. If they work you might expect the genre to fade, but that’s to miss the point. The author is selling hope not answers.

A self-help book needs one big idea and lots of ways of implementing it. Success stories are a must. It’s better to have one idea presented 100 ways, than 100 ideas mentioned once.

Adam Alter teaches marketing at New York’s Stern School of Business. His new book ‘Anatomy of a Breakthrough’ stems from the observation that in East Asian cultures people expect change, while in the West we do not. The book is about how to change, which he defines as coming unstuck.

Alter provides a cheat sheet of 100 ways to do this. Knowing which one to apply highlights the problem with self-help. While a single idea creates the hope we crave, the practical advice is overwhelming and we suffer from choice overload.

Alter does suggest how AI tools can help. When we have an idea it is best to share it beyond friends and family, who will be encouraging but insufficiently critical. A dispassionate voice is precisely why self-help books sell. AI can play the role of constructive critic and rewrite your idea.

Inspired, I turn to Google Bard for ideas about how to be confident.

Anatomy of a Best Seller

Here’s a list of seven ways to be more confident from Bard:

Understand confidence, why it matters and how to use personally and professionally

Identify your strengths and weaknesses to focus on strengths and build on weaknesses

Set realistic goals and breakdown larger ones into a series of manageable steps

Take care of yourself because physical and mental health boosts confidence

Challenge your negative thoughts, replacing them with positive thoughts

Take risks and understand that failure is not the end of the world

Be kind to yourself and forgive yourself your mistakes

That should be good for a few thousand copies.

Why Self-Help Doesn’t Help

We change our minds by changing our emotional state. This is hard to do by thinking about it, but is easier if we move location or get help.

It is common knowledge that we are left or right-brained. This belief is based on the two hemispheres of the brain and the work of Nobel Laureate Roger Sperry on patients whose hemispheres were disconnected as treatment for epilepsy. Left-brained people are logical and right-brained emotional.

Except we’re not like this. While we might handle the syntax of language in our left brain and its emotional tone in the right, our understanding is a result of how well the two sides are connected. Language, like other mental activities, is not contained to a single hemisphere.

There is an important point about knowledge here. Studying exceptions to the rule, such as epilepsy patients, does not prove the rule. You can’t define things by what they are not. I’m not a giraffe, but that reveals little about the human condition.

To prove something we have to try very hard to disprove it. We have to think about the counterfactual, or what might otherwise be true. A book with loads of examples of why something works does not do this.

The Meaning of Confidence

Peter Atwater teaches confidence at William and Mary University in the US and after several years realised he didn’t have a good definition of what it was. He recently published ‘The Confidence Map’ to remedy this.

Atwater notes three concepts of confidence. We have self esteem, with its tendency to over confidence, confidence theatre, when we fake it, and real confidence, which is how we make decisions.

Confidence tricks prey on the vulnerable, so Atwater describes confidence as the opposite of vulnerability. He says this is comfort. But comfort leads to overconfidence and bad decisions, so how do we make good ones?

Control and Certainty as Confidence

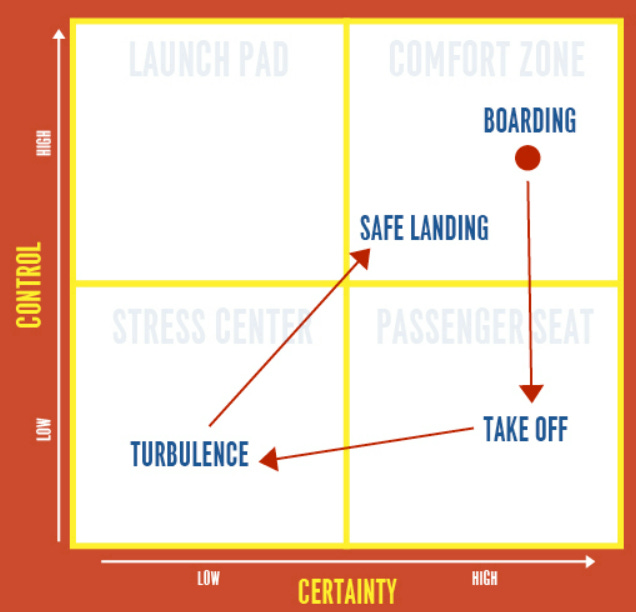

Atwater’s 2x2 model of confidence is based on levels of control and certainty. The diagram below is based on taking a flight.

The diagram explains three of the four states:

High Control, High Confidence or the comfort zone. This is how we feel when boarding, as we choose to do it knowing where we are going and roughly when we’ll arrive. We return here when we land.

Low Control, High Certainty such as on take-off, when we are in the pilot’s hands and familiar with what is happening.

Low Control, Low Certainty that occurs when we hit turbulence, which raises emotional fears. Airlines seek to calm us and offer special training for nervous flyers, using logical processes to battle emotions.

In the comfort zone of high certainty and confidence we don’t want to change. This is why innovation comes from discomfort rather than living your normal life. Atwater notes highly confident politicians, such as those who cannot be voted from office, do rash things that lead to their downfall.

As we don’t fly the plane, the example has no combination of high control with low certainty, which is a shame because this is when most crises of confidence occur. All the big decisions in our lives, such as whom we marry, where we work and how we invest, involve uncertainty about the future. We can improve our control of the situation by spending time with partners, doing research and seeking advice, but the uncertainty remains because the past is an unreliable guide to the future.

Atwater’s quadrant is a better explanation of confidence than a guide to improving it. It explains why one-size-fits-all theories, such as those from books, don’t work well for everyone. Our situations are varied and we have different abilities to control and be certain about outcomes.

Does Confidence Determine Elections?

Atwater starts with the presumption that economic confidence determines election results. He shows this chart from the Huffington Post and explains how his students used it to predict a Trump victory given the slump in economic confidence in the autumn of 2016. Atwater says voter confidence was the decisive factor.

The chart doesn’t run till the election, probably because the polls never showed Trump winning. The 2016 vote, as with Brexit the same year, were stand out failures of polling and thus bad examples of why we should use it to prove a point.

The chart shows that three-quarters of support for both candidates does not change. Economic confidence is a marginal factor, which may explain election results when the candidates are close, but does not explain our core beliefs.

The candidates got close enough for confidence to matter in the summer of 2015. The email scandal that plagued Clinton broke in March that year and is the most likely explanation for the gap closing. Her rivalry with Bernie Sanders would explain her lower support, but not the gains for Trump.

Atwater claims confidence drives human actions, but what he shows is that it drives marginal outcomes.

Confidence in Big Government and Business

When governments react to crises they seek both control and certainty. The grounding of all planes for two days after 9/11 was to reassure the public that the authorities had regained control. Even then, uncertainty was enough for flight traffic to drop 10% in the next three months.

This exertion of control was echoed in lockdowns during Covid. While flights resumed quickly, lockdown dragged on, creating uncertainty about mental health and when normal life would resume. Increased government control means less for individuals.

When politicians try and tough out a character crisis, such as a secret affair or breaking lockdown rules, they lose both control and certainty. Media controls the agenda, while fake memory loss creates uncertainty about character that is worse than the original offence. Politicians revel in confidence theatre, but personal problems reveal them to be as uncertain as the rest of us.

Atwater’s claims about the corporate world may also be challenged. He contrasts the actions of drug maker Johnson and Johnson with Boeing.

Johnson and Johnson was praised for withdrawing Tylenol from shelves in 1982 when a small batch of America’s number one pain killer was laced with cyanide. The drug represented one fifth of the company’s profits, but it chose to protect its reputation. It took control, but it was several years before Tylenol regained number one status.

Boeing blamed pilot error for the 737 MAX Lion Air crash in October 2018. It was not until a similar crash at Ethiopian Airlines the following March that all 387 aircraft were forcibly grounded by the Federal Aviation Administration. The incident is estimated to have cost Boeing $20 billion in fines, compensation and legal fees, and $60 billion in lost orders.

The MAX is Boeing’s best selling plane. It appears no lessons were learned and Boeing is blaming suppliers for the latest safety concerns. The company has a large comfort zone because there is only one competitor and both are propped up by military contracts. Factors other than confidence are at work.

How to Gain Confidence

The best way to gain confidence is to seek help and to practise. Top athletes have coaches and train hard. If you fear public speaking you can hire people to write a speech and teach you to deliver it. The human interaction is more effective in changing your mental state than reading a book about presenting.

Malcolm Gladwell popularised the need to work hard at a skill. Knowing a self help bestseller requires a single, simple idea, he summarised the work of psychologist Anders Ericsson to mean mastering a skill comes from 10,000 hours of practice. The idea has been attacked ever since, but a pithy one-liner creates a persistent meme.

Ericsson said practice must be deliberate. It’s hard to see how 10,000 hours would be anything else. Matthew Syed picks up the theme in ‘Bounce’, a book about hard work over talent, and uses his own experience becoming Britain’s top table tennis player as evidence.

Syed highlights that practice is a function of opportunity. He played on a table in his garage and persisted because of an equally talented brother with whom to practise. Both thrived thanks to a sports master who loved table tennis and ran the only 24-hour club in the county.

In disputing this, researchers at Case Western Reserve University claim to show that practice accounts for only 26% of outcomes in chess, 21% in music and 18% in sports. You won’t make it at basketball if you are five feet tall.

The most accepted studies of practice focus on twins. Identical twins with nearly 100% common genes are more closely matched in ability than fraternal twins with an average 50% commonality. Researchers at Sweden’s Karolinska University found that genes account for 38% of musical talent and that practice is irrelevant. No matter how hard one identical twin tried, their ability was matched by their sibling.

This is a very specific conclusion. The research defines ability as being able to detect differences in pitch, distinguish melodies and recognise rhythms. This leaves ample room for the practising twin to be a better guitar player. What is shown is that talent is somewhat innate, but 38% leaves room for nurture to be twice as important as nature.

Psychologists Gobet and Campitelli report that mastering chess takes between 728 and 16,120 hours, meaning some people need 22 times more practice than others. This is a tremendous argument for the power of persistence, as 16,120 hours is 5½ years of practising eight hours every day.

If you want confidence in your ability to do something then practise it again and again. If you want to go a little faster, then hire a coach. You won’t be certain of success, but with greater control over the process you can be more confident about the outcome.

“Humans are a poorly evolved mammalian species whose adrenalin gland is too big and pre frontal cortex too small”

I often wonder whether self help books should promote what makes the individual a forthright contributor to a healthy society than the vacuous neo liberal idea that only the “community” matters as humanity slowly gets reduced to one category within it ?

I think Mark Blyth nailed the reasons behind Brexit and Trump (likely coining the term “Trumpism”before the Orange one entered the WH

https://youtu.be/rGvZil0qWPg?si=P2OuSO9ZJn4hDzrT

So pollsters, which it must be conceded, are used to try and drive a narrative than gauge actual opinions, did get it hopelessly wrong in 2016 on Brexit and on Trump because from the outset they daren’t risk highlighting the sheer scale of dissatisfaction with the mainstream. Even today pollsters continue driving increasingly incredulous narratives based on minuscule samples to further distance the mainstream from the hopes and desires of the mainstream