Starmer's Green Shoots of Spring

The UK government may be about to do what it was elected to do. It's time to take The Sniff Test.

The month of March is the start of spring in the northern hemisphere. The Sniff Test is unashamedly looking for the green shoots in politics and culture that will shape the next decade. As with all change, the most significant constraint we face is a lack of imagination.

The Builders are Back

The thirty years after the Great Depression represented the high point of government building on both sides of the Atlantic. Europe rebuilt its war torn infrastructure, while the US modernised its vast territory. From the 1970s onwards something changed.

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, authors of Abundance, attribute the change to neoliberalism, an individualistic creed embraced on both left and right. While the right championed self help and a reduced role for government, the left enshrined individual rights that became legal barriers to getting things done. Physical building ground to a halt.

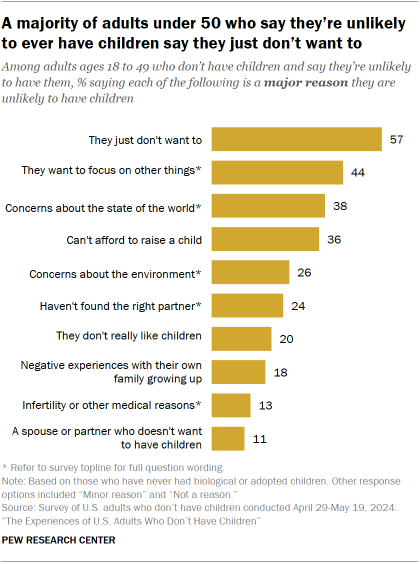

Innovation moved to the digital world. Silicon Valley blossomed, the internet was born from a government communications network, and machine learning gathered pace. This had a profound impact on the work we do, the way we socialise and the mental health of our children. Meanwhile, the scarcity of infrastructure and housing, pushes prices to the point they are a major reason why those children do not have kids of their own.

The criticism that liberalism leads to inequality is at least a couple of hundred years old. While science and technology improve consistently, culture ebbs and flows in waves of individualism and collectivism. This cultural cycle is the core of the Fourth and First Turnings, with the latter a period of rejuvenation and collective harmony. The next decade may be the time to build.

Innovation has turned full circle and is bursting from the digital to the physical world. Behind the leaps and bounds in artificial intelligence is a computing revolution that has completely changed the way automation works. Put simply, where actions were pre-programmed they are now taken on the fly. We may not notice the change in the way our computers run, but we will be amazed by the physical AI walking among us. The Fourth Turning may be the robot revolution.

What is Society?

Humans are social creatures. Teams perform better than collections of individuals and banding together is in everyone’s best interests. Politics is a choice of how to protect the weak from the strong. Society emerges from politics and rises above the tribe, because all that offers is a pecking order without rights.

Enlightenment thinkers framed society as an agreement. Thomas Hobbes, writing after the English Civil War, considered society necessary to escape the brutish state of nature. Power and order are society’s foundations.

John Locke was more optimistic a century later. He required society to apply an impartial rule of law to protect rights. He believed these were derived through reason and that reasonable people would agree to respect each other’s life, liberty and property.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that the collective will was required to set humans free. Without this, society and property rights in particular introduce inequality. Sovereignty must reside in the people.

These thinkers shaped the American and French revolutions and numerous constitutions in the West. Free speech, freedom of religion and ownership of property, extend from these philosophies.

By the middle of the following century the consequences of the industrial revolution were unfolding. Marx saw the social contract as a smokescreen protecting the privileges of the ruling classes. Collective emancipation required a classless society, to be brought about by force if necessary.

The idea of oppressor and oppressed lies beneath most cultural movements. Marx’s ideas are the foundation of feminism and the conspiracy theories of systemic racism and the deep state. Your allegiance to left or right can be predicted by the theory you sympathise with most.

In the 20th century Paul-Michel Foucault described a disciplinary society, where people are controlled by surveillance, behavioural norms and the interpretations of expert opinion, rather than overt force. We engage in self censorship, or did until online anonymity loosened the bile of an opinionated minority. Now we must balance the right to speak without fear of reprisal, against incitement by anonymous cowards.

Society is a fluctuating balance between individual freedoms and collective purpose. Underneath each point on the spectrum from libertarianism to communism, lies a moral choice and an emotional justification for believing it. These moralities are combinations of desires for security, human rights and civic responsibility. The waxing and waning of collective conviction in each, is what we call culture.

Green Shoots in Government

Free speech and private property are individualistic, while national security, public welfare, education and health are collective goals. The level of taxation is a proxy for the state of the balance between the two. The Labour party is exploring the limits of our tolerance for collectivism. Its recent policies hint at a return to the election campaign promises of competent government, following a succession of failures from pursuing ideological ends.

This week Liz Kendall announced changes to welfare aimed at saving £5 billion. The measures are a veiled acknowledgement that too many people are paid not to work. By raising universal credit, while reducing its health element and making it harder to qualify, the government aims to nudge more people into employment.

This comes hard on the heels of Wes Streeting announcing the abolition of NHS England and the loss of half its jobs. This is a transparent attack on excessive administration in the health service. Streeting is correct to claim only Labour can reform the NHS, but that is no guarantee of success. He is taking laps of honour for eliminating the failed reforms of the Cameron administration, while all people care about is being able to see a doctor.

The recognition of limits on the collective will is however, a step in the right direction. The annual health service budget is almost £220 billion across the four nations of the UK. This has grown around 5% over each of the past 10 years. Population growth over the same period was 4.5% a year.

Successive governments put too much emphasis on how much money they spend and too little on what it buys us. A third of us believe wait times for appointments are too long. A shortage of doctors means each GP looks after an average of 2,258 patients. Across all public services, 7 in 10 people believe the quality falls short.

People support paying taxes when they believe they get value for money. The rightward political shift signals a reduction in belief, but not an abandonment. Political parties have turned spending into a shouting match about whose morality is most worthy. The cyclical theories of history, such as the Fourth Turning, are about tectonic shifts in cultural foundations. The tantalising promise of the 2030s is a culture that demands and receives effective government.

The Robot Revolution

This week the technology world was held spellbound by the annual NVIDIA GTC. Jenson Huang, the company’s founder, revealed a series of breakthroughs and new launches to supercharge computing capacity over the next three years. This is now sufficient for robots to have system one and two thought processes, just as Kahneman described in humans.

In practice, this means a robot can perform a routine task, while figuring out how to do it better. As machines are connected in a hive mind, they learn from each other. Your self-driving car will be better because of the close shave I had in mine. This is a society of robots learning from each other and developing at superhuman speed as a consequence.

Huang believes a billion human knowledge workers will have ten billion AI assistants. Predictions for the numbers of physical robots by mid century range from a few hundred million to ten billion. The constraint is the materials required to build them, rather than a debate over their usefulness. As machines accelerate our ability to experiment, they will change the way they are built, leaving those low end forecasts looking hopelessly pessimistic.

Scarcity and Abundance

The belief that the supply of copper constrains the potential of artificial intelligence is scarcity thinking. It’s common in today’s politics. Scarcity says the answer to climate change is to reverse economic growth. It says the answer to a housing shortage is to deport people. Scarcity puts tariffs on neighbours because it sees a finite economic pie.

Abundance gets a bad name from the enthusiasm of its strongest proponents. They rave about curing every disease, living to age two hundred and rant about excessive government regulation. As optimists however, they will be more right than wrong.

Both liberals and collectivists may be pessimistic or optimistic, believing in scarcity or abundance. The liberal insistence on individual rights has morphed into the constraints society places on growth. We see this in nimbyism. We see it in planning laws that restrict the number of houses, so we have a cost of living crisis, a baby bust and a society divided into haves and have nots. The collectivists hold us back with the morass of environmental and zoning rules that prevent the building of runways and high speed rail.

Listen carefully and you will hear rumblings of an increased spiritualism and a religious revival to rebuild our faith in community. Technology is always about the next decade, while politics rarely is. Now there is a groundswell of serious thinking about what the future looks like.

Much of this comes, like Klein and Thompson, from the progressive left and a realisation that it must tack back to the centre to rediscover its purpose. This means accepting the diagnosis of government failure from the right and demonstrating that reform rather than reduction is the answer.

This is what Keir Starmer promised us and why he was elected. We watch, we wait, we hope and in time we will vote.